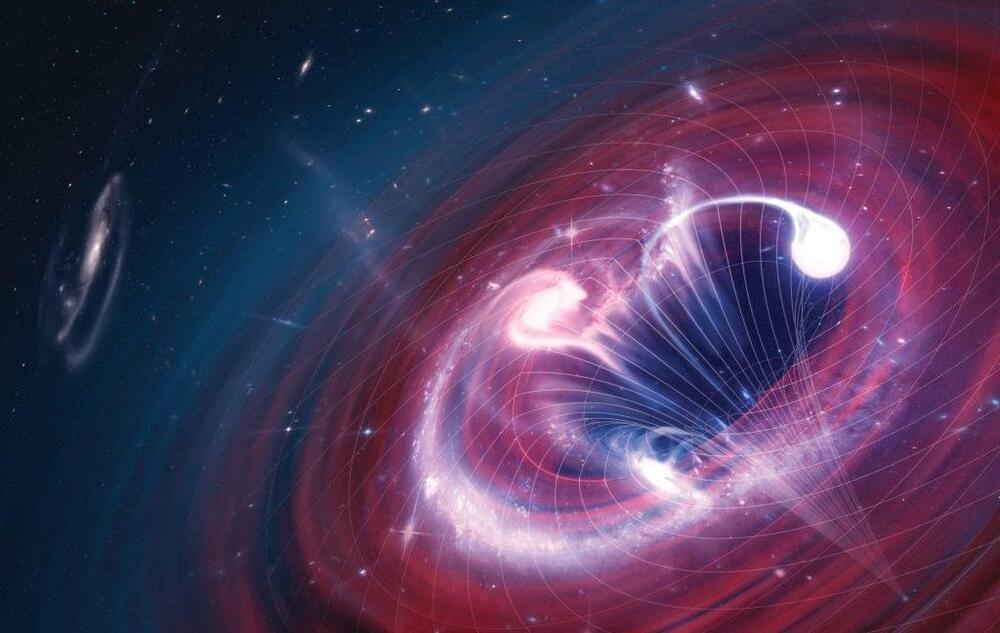

Was dark matter created some time after the Big Bang? Gravitational wave detectors could soon find the answer.

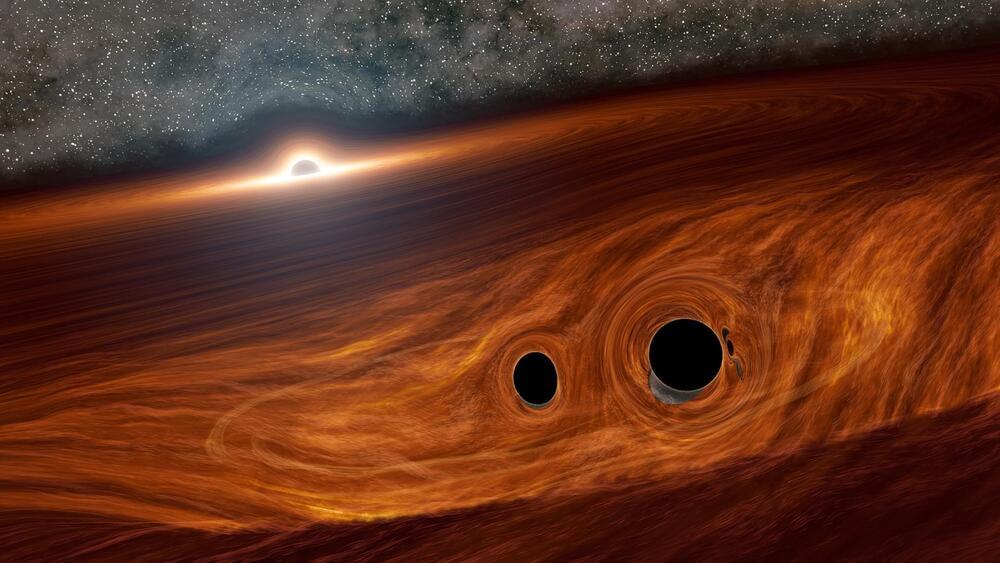

For now, the duo’s results suggest that the Dark Big Bang is far less constrained by past observations than Freese and Winkler originally anticipated. As Ilie explains, their constraints could soon be put to the test.

“We examined two Dark Big Bang scenarios in this newly found parameter space that produce gravitational wave signals in the sensitivity ranges of existing and upcoming surveys,” he says. “In combination with those considered in Freese and Winkler’s paper, these cases could form a benchmark for gravitational wave researchers as they search for evidence of a Dark Big Bang in the early universe.”