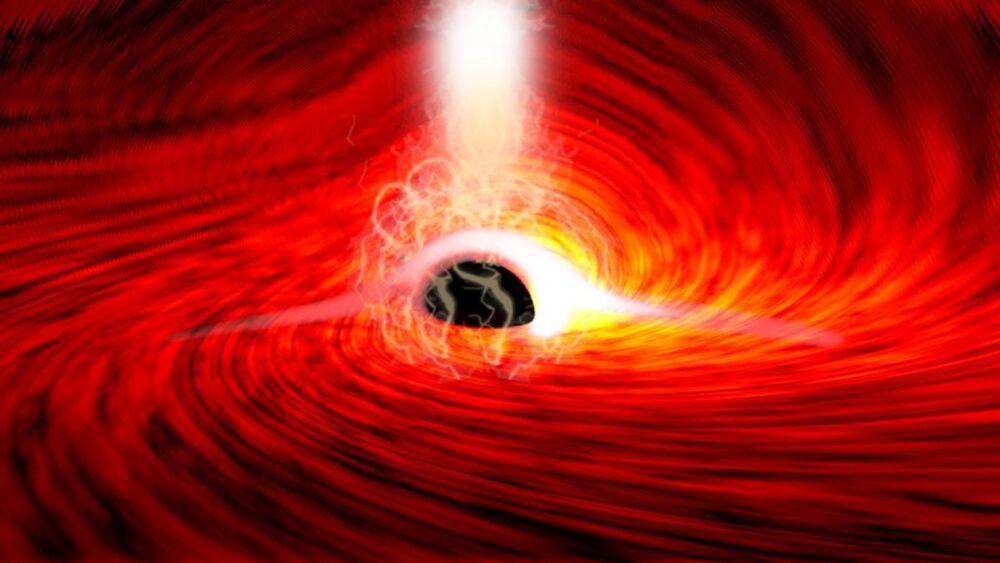

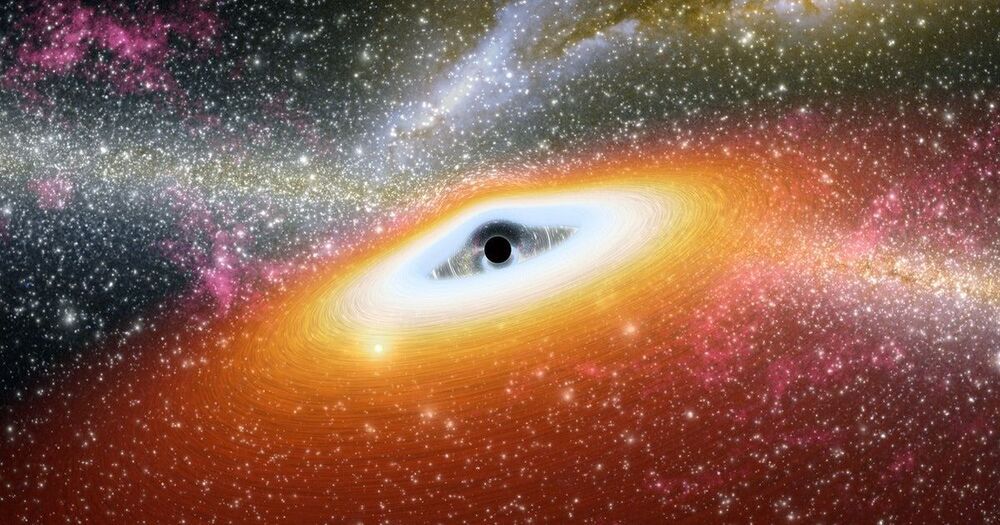

In the depths of space, there are celestial bodies where extreme conditions prevail: Rapidly rotating neutron stars generate super-strong magnetic fields. And black holes, with their enormous gravitational pull, can cause huge, energetic jets of matter to shoot out into space. An international physics team with the participation of the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) has now proposed a new concept that could allow some of these extreme processes to be studied in the laboratory in the future: A special setup of two high-intensity laser beams could create conditions similar to those found near neutron stars. In the discovered process, an antimatter jet is generated and accelerated very efficiently. The experts present their concept in the journal Communications Physics.

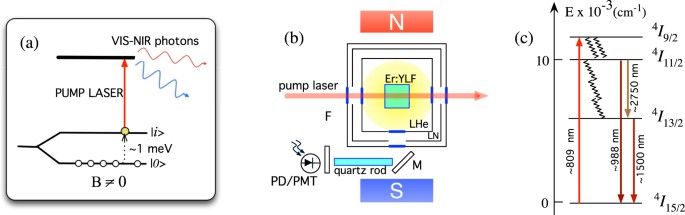

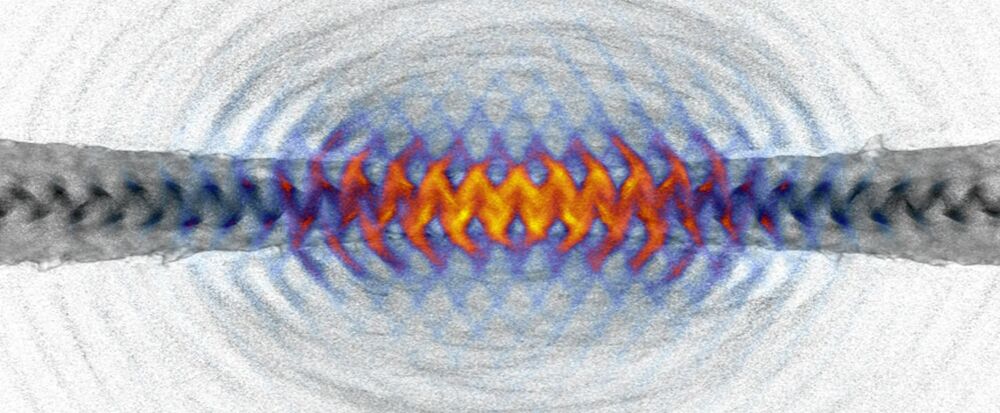

The basis of the new concept is a tiny block of plastic, crisscrossed by micrometer-fine channels. It acts as a target for two lasers. These simultaneously fire ultra-strong pulses at the block, one from the right, the other from the left — the block is literally taken by laser pincers. “When the laser pulses penetrate the sample, each of them accelerates a cloud of extremely fast electrons,” explains HZDR physicist Toma Toncian. “These two electron clouds then race toward each other with full force, interacting with the laser propagating in the opposite direction.” The following collision is so violent that it produces an extremely large number of gamma quanta — light particles with an energy even higher than that of X-rays.

The swarm of gamma quanta is so dense that the light particles inevitably collide with each other. And then something crazy happens: According to Einstein’s famous formula E=mc2, light energy can transform into matter. In this case, mainly electron-positron pairs should be created. Positrons are the antiparticles of electrons. What makes this process special is that “very strong magnetic fields accompany it,” describes project leader Alexey Arefiev, a physicist at the University of California at San Diego. “These magnetic fields can focus the positrons into a beam and accelerate them strongly.” In numbers: Over a distance of just 50 micrometers, the particles should reach an energy of one gigaelectronvolt (GeV) — a size that usually requires a full-grown particle accelerator.