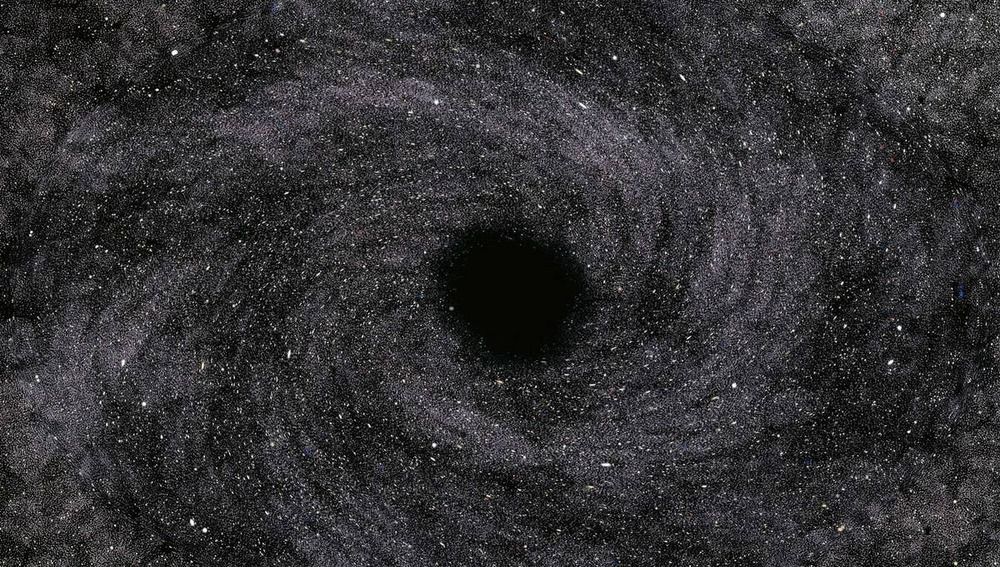

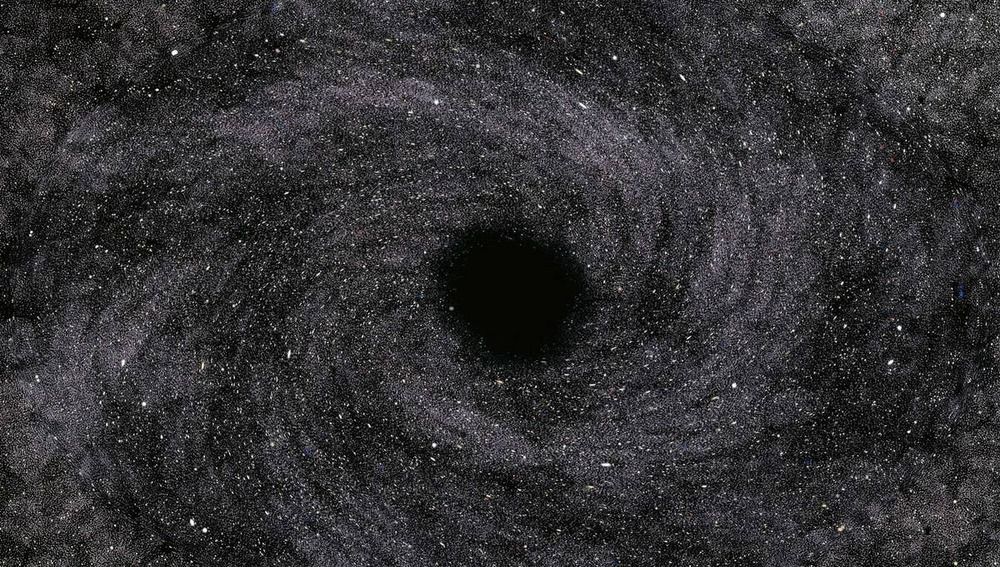

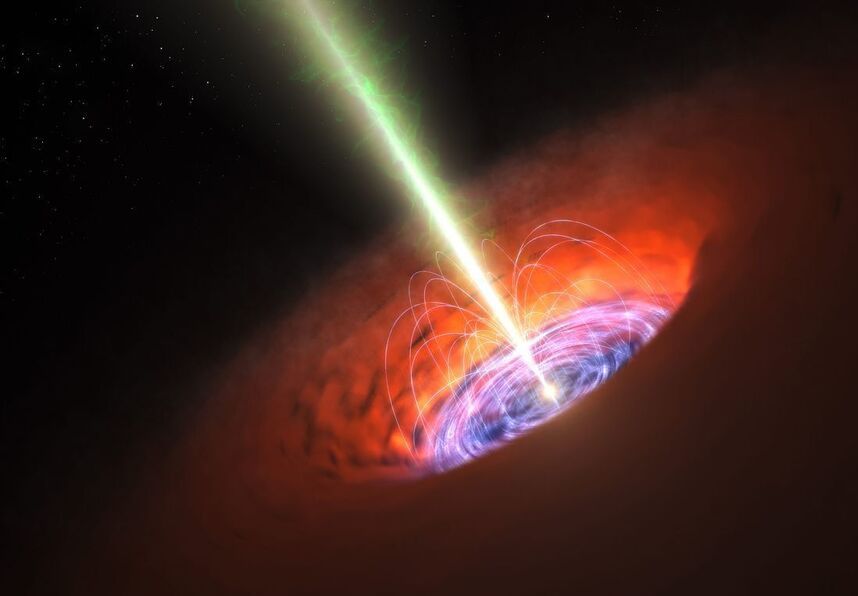

There’s no denying that black holes are the most destructive force in the universe, with their swirling, light-swallowing maw devouring anything that crosses its perilous event horizon.

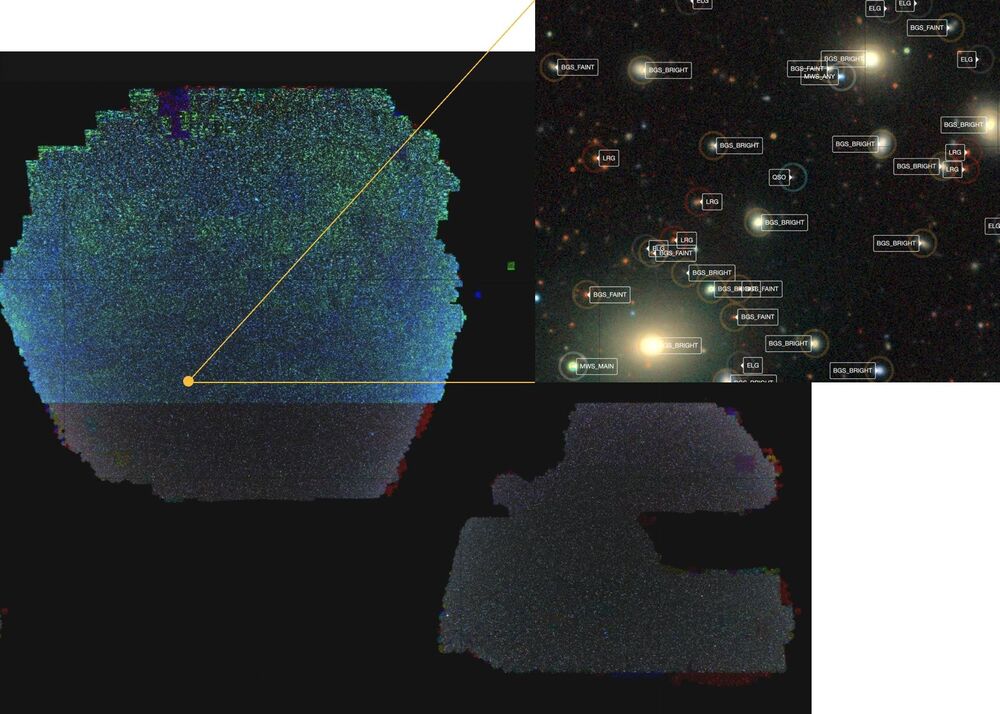

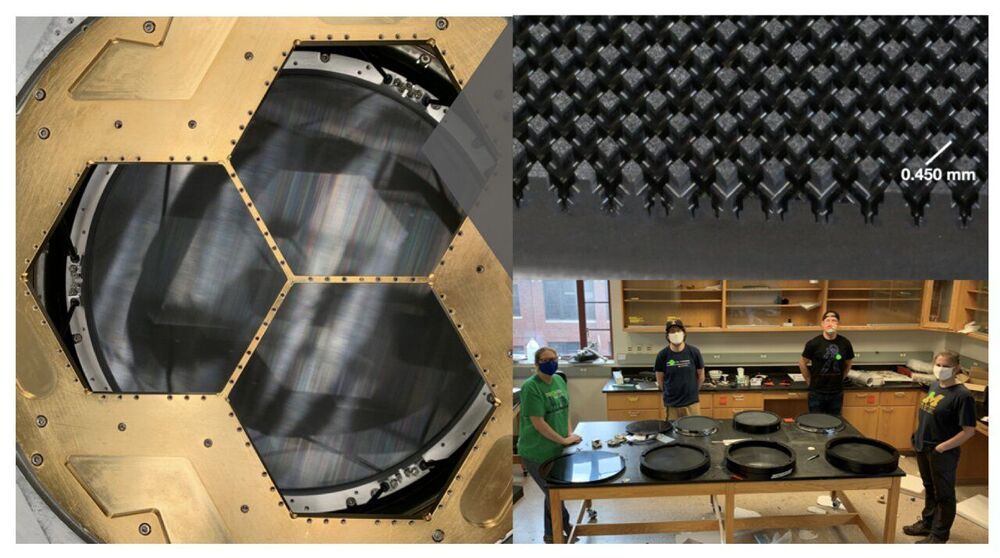

The Beijing-Arizona Sky Survey (BASS) team of National Astronomical Observatories of Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC) and their collaborators of the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) project released a giant 2D map of the universe, which paves the way for the upcoming new-generation dark energy spectroscopic survey.

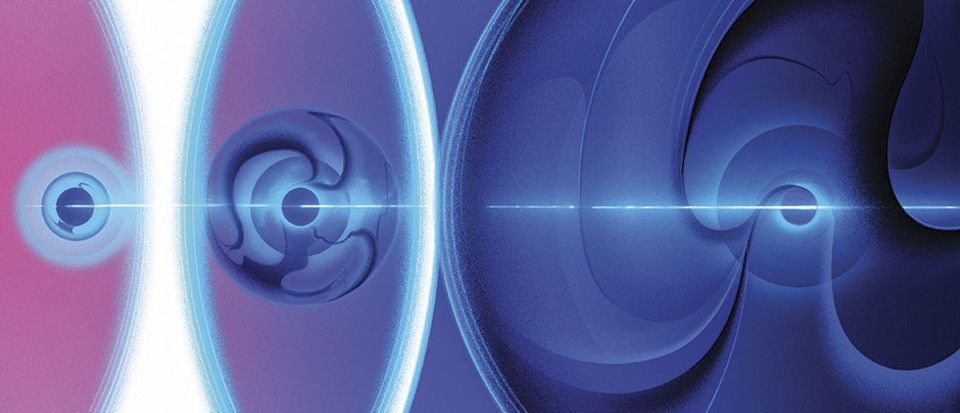

Modern astronomical observations reveal that the universe is expanding and appears to be accelerating. The power driving the expansion of the universe is called dark energy by astronomers. Dark energy is still a mystery and accounts for about 68% of the substance of the universe.

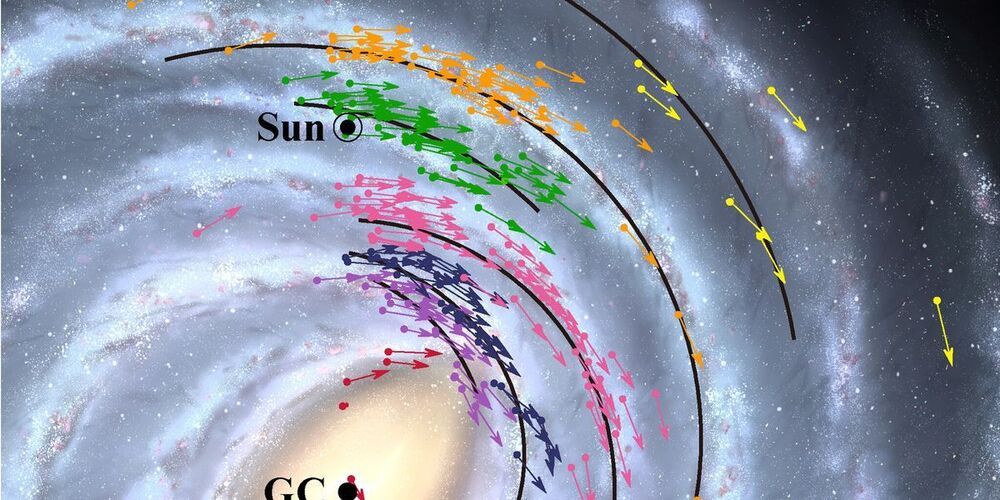

Large-scale redshift measurements of galaxies can describe the 3D distribution of the matter and reveal the effect of dark energy on the expansion of the universe.

Great new episode with Alex Filippenko, a University of California, Berkeley astronomer, who was part of the Nobel-winning teams that discovered dark energy in the late 1990s. Please listen.

Nearly 25 years after its discovery, the mystery at the core of dark energy persists. Astronomers are no closer to understanding what’s behind this cosmic repulsive force that counteracts gravity and causes the cosmos to expand at an accelerating rate than when it was first discovered in 1998. Guest Alexei Filippenko is a member of the Nobel Prize-winning team that detected dark energy via supernovae surveys. He gives us the inside scoop on how dark energy was detected; what it means for our existence and the prospects for unmasking this bizarre force of nature that makes up some 70 percent of the observable universe.

The cosmic microwave background, or CMB, is the electromagnetic echo of the Big Bang, radiation that has been traveling through space and time since the very first atoms were born 380000 years after our universe began. Mapping minuscule variations in the CMB tells scientists about how our universe came to be and what it’s made of.

New observations of the first black hole ever detected have led astronomers to question what they know about the Universe’s most mysterious objects.

Published today (February 182021) in the journal Science, the research shows the system known as Cygnus X-1 contains the most massive stellar-mass black hole ever detected without the use of gravitational waves.

Cygnus X-1 is one of the closest black holes to Earth. It was discovered in 1964 when a pair of Geiger counters were carried on board a sub-orbital rocket launched from New Mexico.

In the last decade, we’ve taken photos of a black holes, peered into the heart of atoms and looked back at the birth of the Universe. And yet, there are yawning gaps in our understanding of the Universe and the laws that govern it. These are the mysteries that will be troubling physicists and astronomers over the next decade and beyond.

Dark matter, the nature of time, aliens and supermassive black holes: these seven things will be puzzling astronomers for years to come.

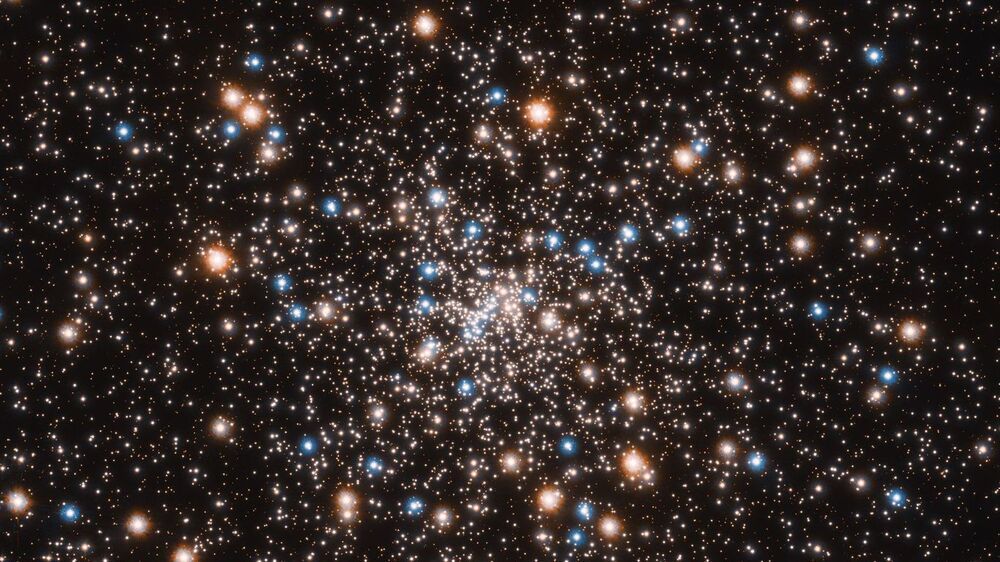

Scientists were expecting to find an intermediate-mass black hole at the heart of the globular cluster NGC 6397, but instead they found evidence of a concentration of smaller black holes lurking there. New data from the NASA /ESA Hubble Space Telescope have led to the first measurement of the extent of a collection of black holes in a core-collapsed globular cluster.

Globular clusters are extremely dense stellar systems, in which stars are packed closely together. They are also typically very old — the globular cluster that is the focus of this study, NGC 6397, is almost as old as the Universe itself. It resides 7800 light-years away, making it one of the closest globular clusters to Earth. Because of its very dense nucleus, it is known as a core-collapsed cluster.