Have you ever seen the popular movie called The Matrix? In it, the main character Neo realizes that he and everyone else he had ever known had been living in a computer-simulated reality. But even after taking the red pill and waking up from his virtual world, how can he be so sure that this new reality is the real one? Could it be that this new reality of his is also a simulation? In fact, how can anyone tell the difference between simulated reality and a non-simulated one? The short answer is, we cannot. Today we are looking at the simulation hypothesis which suggests that we all might be living in a simulation designed by an advanced civilization with computing power far superior to ours.

The simulation hypothesis was popularized by Nick Bostrum, a philosopher at the University of Oxford, in 2003. He proposed that members of an advanced civilization with enormous computing power may run simulations of their ancestors. Perhaps to learn about their culture and history. If this is the case he reasoned, then they may have run many simulations making a vast majority of minds simulated rather than original. So, there is a high chance that you and everyone you know might be just a simulation. Do not buy it? There is more!

According to Elon Musk, if we look at games just a few decades ago like Pong, it consisted of only two rectangles and a dot. But today, games have become very realistic with 3D modeling and are only improving further. So, with virtual reality and other advancements, it seems likely that we will be able to simulate every detail of our minds and bodies very accurately in a few thousand years if we don’t go extinct by then. So games will become indistinguishable from reality with an enormous number of these games. And if this is the case he argues, “then the odds that we are in base reality are 1 in billions”.

There are other reasons to think we might be in a simulation. For example, the more we learn about the universe, the more it appears to be based on mathematical laws. Max Tegmark, a cosmologist at MIT argues that our universe is exactly like a computer game which is defined by mathematical laws. So for him, we may be just characters in a computer game discovering the rules of our own universe.

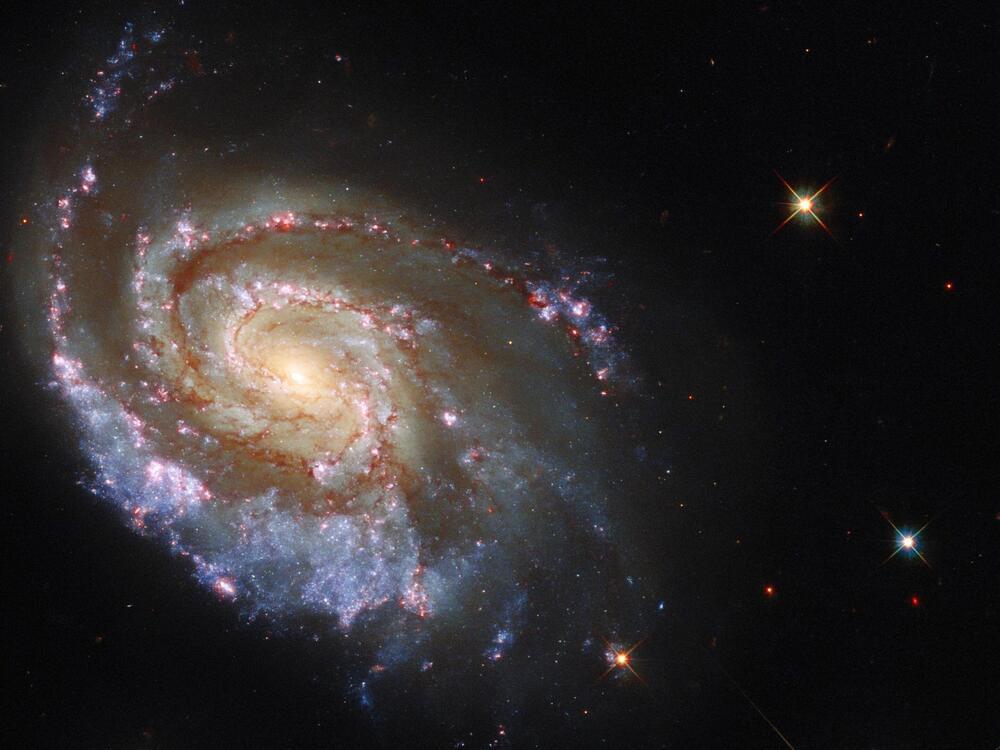

With our current understanding of the universe, it seems impossible to simulate the entire universe given a potentially infinite number of things within it. But would we even need to? All we need to simulate is the actual minds that are occupying the simulated reality and their immediate surroundings. For example, when playing a game, new environments render as the player approaches them. There is no need for those environments to exist prior to the character approaching them since this can save a lot of computing power. This can be especially true of simulations that are as big as our universe. So, it could be argued that distant galaxies, atoms, and anything that we are actively not observing simply does not exist. These things render into existence once someone starts to observe them.

On his podcast StarTalk, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson and comedian Chuck Nice discussed the simulation hypothesis. Nice suggested that maybe there is a finite limit to the speed of light because if there wasn’t, we would be able to reach other galaxies very quickly. Tyson was surprised by this statement and further added that the programmer put in this limit to make sure we cannot get too far away places before the programmer has the time to program them.