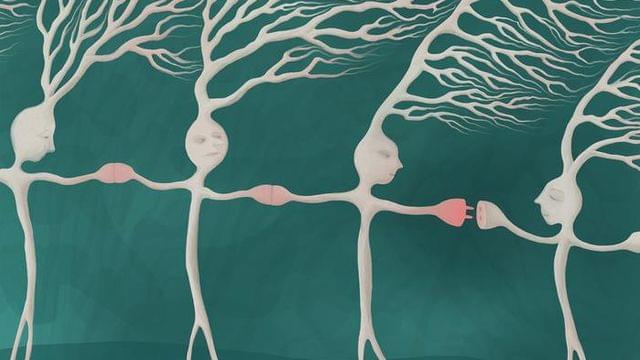

They are part of the brain of almost every animal species, yet they remain usually invisible even under the electron microscope. “Electrical synapses are like the dark matter of the brain,” says Alexander Borst, director at the MPI for Biological Intelligence, in foundation (i.f). Now a team from his department has taken a closer look at this rarely explored brain component: In the brain of the fruit fly Drosophila, they were able to show that electrical synapses occur in almost all brain areas and can influence the function and stability of individual nerve cells.

Neurons communicate via synapses, small contact points at which chemical messengers transmit a stimulus from one cell to the next. We may remember this from biology class. However, that is not the whole story. In addition to the commonly known chemical synapses, there is a second, little-known type of synapse: the electrical synapse. “Electrical synapses are much rarer and are hard to detect with current methods. That’s why they have hardly been researched so far,” explains Georg Ammer, who has long been fascinated by these hidden cell connections. “In most animal brains, we therefore don’t know even basic things, such as where exactly electrical synapses occur or how they influence brain activity.”

An electrical synapse connects two neurons directly, allowing the electrical current that neurons use to communicate, to flow from one cell to the next without a detour. Except in echinoderms, this particular type of synapse occurs in the brain of every animal species studied so far. “Electrical synapses must therefore have important functions: we just do not know which ones!” says Georg Ammer.