Black holes are a hot topic in the news these days.

Black holes – regions in space where gravity is so strong that nothing can escape – are a hot topic in the news these days.

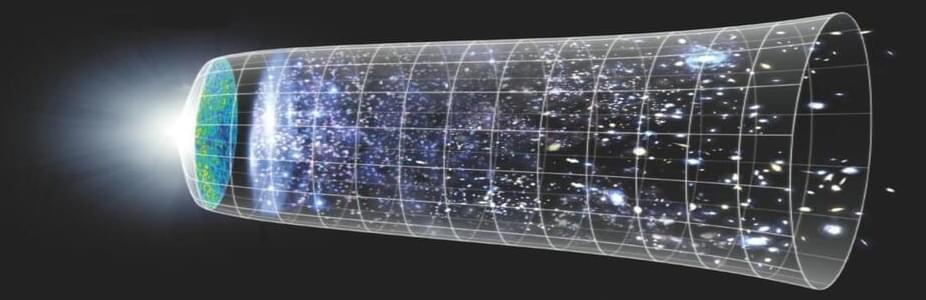

The Big Bang still happened a very long time ago, but it wasn’t the beginning we once supposed it to be.

Where did all this come from? In every direction we care to observe, we find stars, galaxies, clouds of gas and dust, tenuous plasmas, and radiation spanning the gamut of wavelengths: from radio to infrared to visible light to gamma rays. No matter where or how we look at the universe, it’s full of matter and energy absolutely everywhere and at all times. And yet, it’s only natural to assume that it all came from somewhere. If you want to know the answer to the biggest question of all — the question of our cosmic origins — you have to pose the question to the universe itself, and listen to what it tells you.

Today, the universe as we see it is expanding, rarifying (getting less dense), and cooling. Although it’s tempting to simply extrapolate forward in time, when things will be even larger, less dense, and cooler, the laws of physics allow us to extrapolate backward just as easily. Long ago, the universe was smaller, denser, and hotter. How far back can we take this extrapolation? Mathematically, it’s tempting to go as far as possible: all the way back to infinitesimal sizes and infinite densities and temperatures, or what we know as a singularity. This idea, of a singular beginning to space, time, and the universe, was long known as the Big Bang.

Thanks to LastPass for sponsoring PBS DS. You can check out LastPass by going to https://lastpass.onelink.me/HzaM/2019Q3JulyPBSspace.

PBS Member Stations rely on viewers like you. To support your local station, go to: http://to.pbs.org/DonateSPACE

Our universe started with the big bang. But only for the right definition of “our universe”. And of “started” for that matter. In fact, probably the Big Bang is nothing like what you were taught.

A hundred years ago we discovered the beginning of the universe. Observations of the retreating galaxies by Edwin Hubble and Vesto Slipher, combined with Einstein’s then-brand-new general theory of relativity, revealed that our universe is expanding. And if we reverse that expansion far enough – mathematically, purely according to Einstein’s equations, it seems inevitable that all space and mass and energy should once have been compacted into an infinitesimally small point – a singularity. It’s often said that the universe started with this singularity, and the Big Bang is thought of as the explosive expansion that followed. And before the Big Bang singularity? Well, they say there was no “before”, because time and space simply didn’t exist. If you think you’ve managed to get your head around that bizarre notion then I have bad news. That picture is wrong. At least, according to pretty much every serious physicist who studies the subject. The good news is that the truth is way cooler, at least as far as we understand it.

Check out the new Space Time Merch Store!

https://pbsspacetime.com/

Support Space Time on Patreon.

https://www.patreon.com/pbsspacetime.

Hosted by Matt O’Dowd.

Have you ever seen the popular movie called The Matrix? In it, the main character Neo realizes that he and everyone else he had ever known had been living in a computer-simulated reality. But even after taking the red pill and waking up from his virtual world, how can he be so sure that this new reality is the real one? Could it be that this new reality of his is also a simulation? In fact, how can anyone tell the difference between simulated reality and a non-simulated one? The short answer is, we cannot. Today we are looking at the simulation hypothesis which suggests that we all might be living in a simulation designed by an advanced civilization with computing power far superior to ours.

The simulation hypothesis was popularized by Nick Bostrum, a philosopher at the University of Oxford, in 2003. He proposed that members of an advanced civilization with enormous computing power may run simulations of their ancestors. Perhaps to learn about their culture and history. If this is the case he reasoned, then they may have run many simulations making a vast majority of minds simulated rather than original. So, there is a high chance that you and everyone you know might be just a simulation. Do not buy it? There is more!

According to Elon Musk, if we look at games just a few decades ago like Pong, it consisted of only two rectangles and a dot. But today, games have become very realistic with 3D modeling and are only improving further. So, with virtual reality and other advancements, it seems likely that we will be able to simulate every detail of our minds and bodies very accurately in a few thousand years if we don’t go extinct by then. So games will become indistinguishable from reality with an enormous number of these games. And if this is the case he argues, “then the odds that we are in base reality are 1 in billions”.

There are other reasons to think we might be in a simulation. For example, the more we learn about the universe, the more it appears to be based on mathematical laws. Max Tegmark, a cosmologist at MIT argues that our universe is exactly like a computer game which is defined by mathematical laws. So for him, we may be just characters in a computer game discovering the rules of our own universe.

With our current understanding of the universe, it seems impossible to simulate the entire universe given a potentially infinite number of things within it. But would we even need to? All we need to simulate is the actual minds that are occupying the simulated reality and their immediate surroundings. For example, when playing a game, new environments render as the player approaches them. There is no need for those environments to exist prior to the character approaching them since this can save a lot of computing power. This can be especially true of simulations that are as big as our universe. So, it could be argued that distant galaxies, atoms, and anything that we are actively not observing simply does not exist. These things render into existence once someone starts to observe them.

On his podcast StarTalk, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson and comedian Chuck Nice discussed the simulation hypothesis. Nice suggested that maybe there is a finite limit to the speed of light because if there wasn’t, we would be able to reach other galaxies very quickly. Tyson was surprised by this statement and further added that the programmer put in this limit to make sure we cannot get too far away places before the programmer has the time to program them.

It’s awe-inspiring to realize that there is a complex intelligence in every living cell. Two questions arise: Is it the intelligence of the cell? That seems inconsistent with how we usually use the word “intelligence.” If we see that a one-celled life form functions with lot of intelligence, perhaps it is more like a book that contains great ideas. Paper doesn’t create ideas; neither, by itself, does protoplasm. Something else is at work.

If the cell itself does not create the intelligence it embodies, what does? Panpsychists argue that all of nature participates in some way in consciousness and humans are the most highly developed example. Theists argue that only a mind outside the universe could create something like human consciousness.

As we learn more and more about the intricate complexities of nature, perhaps debates over the origin of life, intelligence, consciousness, and similar topics will increasingly be between panpsychists and theists rather than materialists and theists. A whole new environment.

Sabine Hossenfelder, Anil Seth, Massimo Pigliucci & Anders Sandberg discuss whether humanity is stuck in the matrix.

If you enjoy this video check out more content on the mind, reality and reason from the world’s biggest speakers at https://iai.tv/debates-and-talks?channel=philosophy%3Amind-a…the-matrix.

00:00 Introduction.

02:21 Anders Sandberg | We could be living in a superior race’s simulation.

04:16 Sabine Hossenfelder | The simulation hypothesis is pseudoscience.

06:20 Anil Seth | Is whether we are a simulation even important?

09:29 Massimo Pigliucci | The mind is too complex to be replicated.

13:14 Is it reasonable to question the existence of reality?

23:55 How do we define reality?

29:34 Are we victim to Hollywood fantasy?

Are we living in a computer simulated reality? Until recently the possibility that we are living in a computer simulation was largely limited to fans of The Matrix with an over active imagination or sci-fi fantasists. But now some are arguing that strange quirks of our universe, like the indeterminateness of quantum theory and the black hole information paradox are evidence that our reality is in actuality a created simulation. Moreover, tech guru Elon Musk has come out supporting the theory, arguing that ““we are most likely in a simulation””.

Should we take the idea that we are living in a computer simulation seriously? Groundbreaking consciousness researcher Anil Seth, stoic philosopher Massimo Pigliucci, maverick physicist and Youtube sensation Sabine Hossenfelder and Oxford transhumanist Anders Sandberg ask if we are stuck in the matrix. The debate is hosted by Güneş Taylor.

#AnilSeth #MassimoPigliucci #ComputerSimulatedReality.

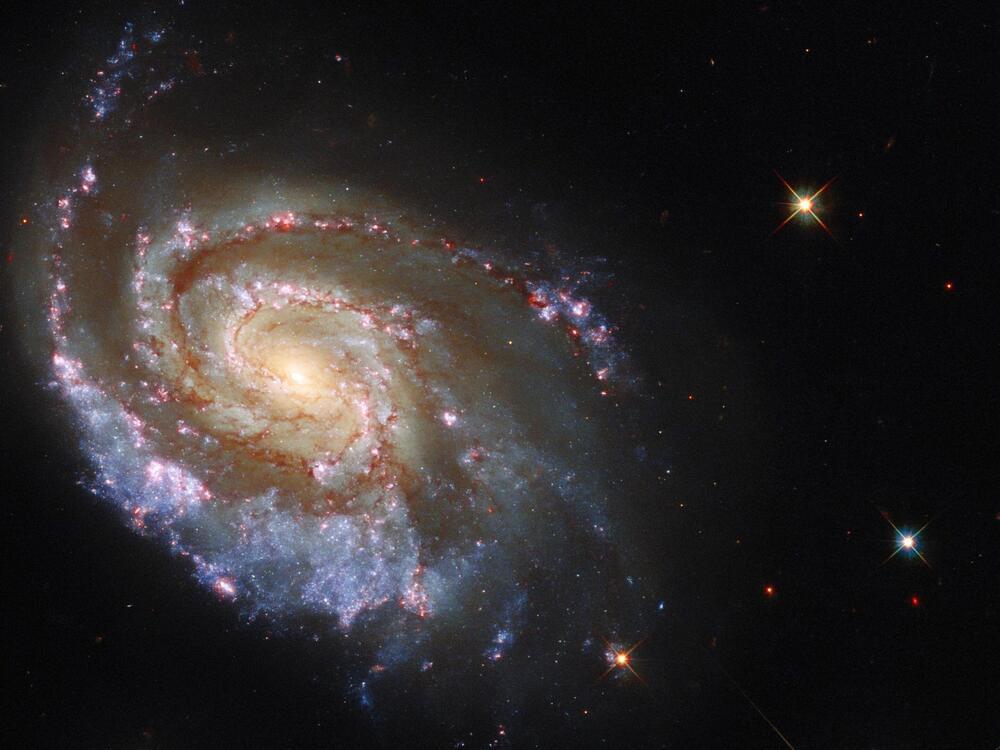

NASA /ESA Hubble Space Telescope Picture of the Week features the galaxy NGC 6,984 an elegant spiral galaxy in the constellation Indus roughly 200 million light-years away from Earth. The galaxy is a familiar sight for Hubble, having already been captured in 2013. The sweeping spiral arms are threaded through with a delicate tracery of dark lanes of gas and dust, and studded with bright stars and luminous star-forming regions.

These new observations were made following an extremely rare astronomical event — a double supernova in NGC 6984. Supernovae are unimaginably violent explosions on a truly vast scale, precipitated by the deaths of massive stars. These events are powerful but rare and fleeting — a single supernova can outshine its host galaxy for a brief time. The discovery of two supernovae at virtually the same time and location (in astronomical terms) prompted speculation from astronomers that the two supernovae may somehow be physically linked. Using optical and ultraviolet observations from Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 astronomers sought to get a better look at the site of the two supernovae, hopefully allowing them to discover if the two supernova explosions were indeed linked. Their findings could give astronomers important clues into the lives of binary stars.

As well as helping to unravel an astronomical mystery, these new observations added more data to the 2013 observations, and allowed this striking new image to be created. The observations — each of which covers only a narrow range of wavelengths — add new details and a greater range of colors to the image.

VR can soon become perceptually indistinguishable from the physical reality, even superior in many practical ways, and any artificially created “imaginary” world with a logically consistent ruleset of physics would be ultrarealistic. Advanced immersive technologies incorporating quantum computing, AI, cybernetics, optogenetics and nanotech would make this a new “livable” reality within the next few decades. Can this new immersive tech help us decipher the nature of our own “b… See more.

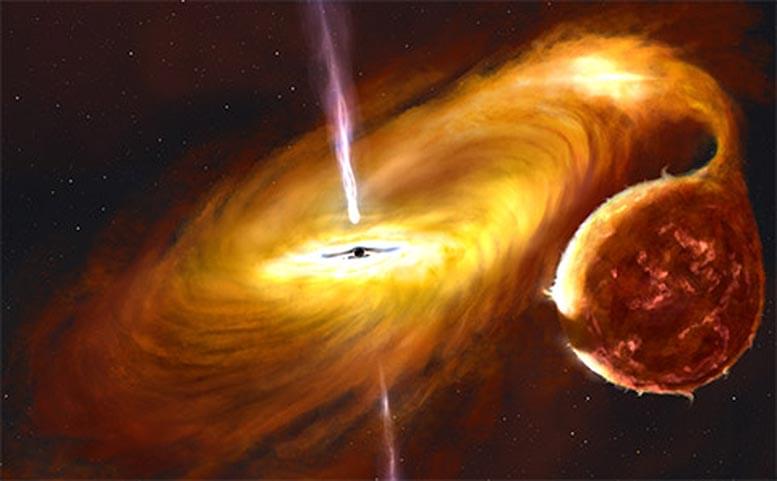

An international team of astrophysicists from South Africa, the UK, France and the US have found large variations in the brightness of light seen from around one of the closest black holes in our Galaxy, 9,600 light-years from Earth, which they conclude is caused by a huge warp in its accretion disc.

This object, MAXI J1820+070, erupted as a new X-ray transient in March 2018 and was discovered by a Japanese X-ray telescope onboard the International Space Station. These transients, systems that exhibit violent outbursts, are binary stars, consisting of a low-mass star, similar to our Sun and a much more compact object, which can be a white dwarf 0 neutron star 0 or black hole. In this case, MAXI J1820+070 contains a black hole that is at least 8 times the mass of our Sun.

The first findings have now been published in the international highly ranked journal, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, whose lead author is Dr. Jessymol Thomas, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO).

For the first time, physicists have been able to directly measure one of the ways exploding stars forge the heaviest elements in the Universe.

By probing an accelerated beam of radioactive ions, a team led by physicist Gavin Lotay of the University of Surrey in the UK observed the proton-capture process thought to occur in core-collapse supernovae.

Not only have scientists now seen how this happens in detail, the measurements are allowing us to better understand the production and abundances of mysterious isotopes called p-nuclei.