Two direct-detection experiments see no evidence of a signal reported by their predecessor.

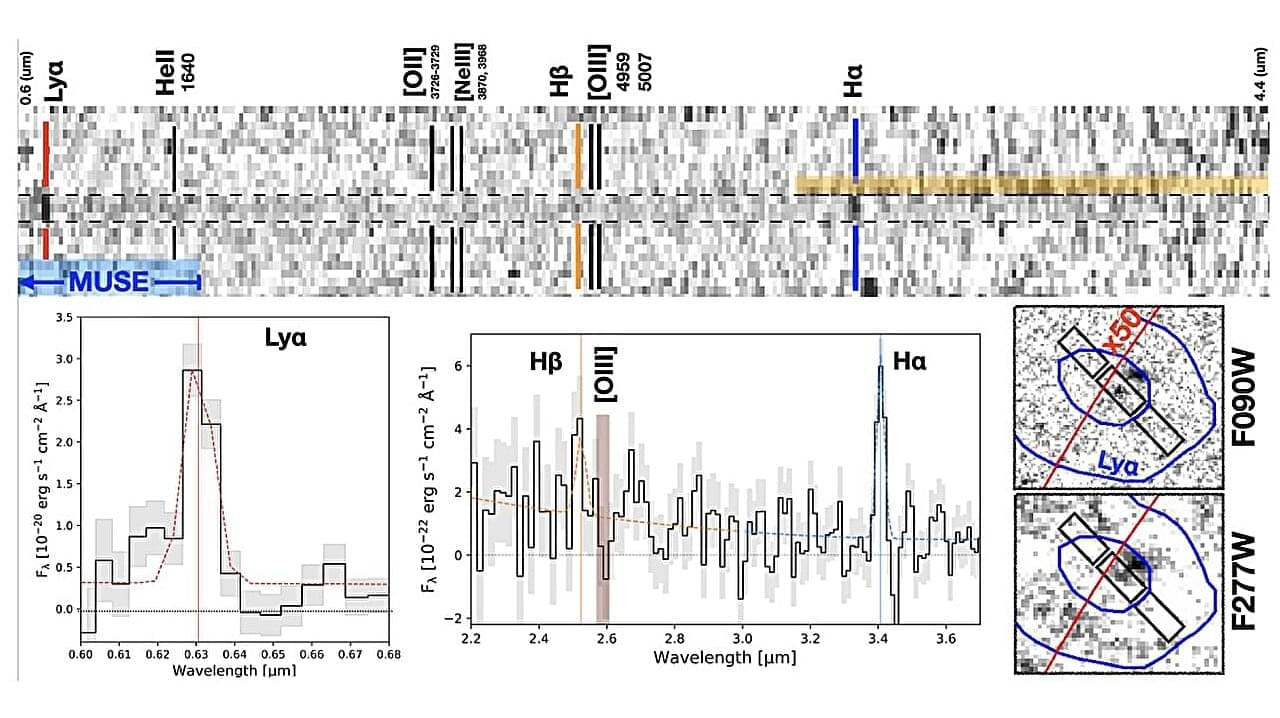

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have detected what appears to be a faint and small star-forming complex. The discovery of the new complex, which received the designation LAP2, is detailed in a research paper published Sept. 8 on the arXiv preprint server.

The hypothetical Population III stars, composed almost entirely of primordial gas, are theorized to be the first stars to form after the Big Bang. Finding very low-metallicity, low-mass sources at high-redshifts could be crucial to investigating these stars, as they provide a rare glimpse of galaxies under conditions similar to those of the early universe. This could help us understand, for instance, how the first generations of stars enriched the cosmos with heavier elements.

Recently, a team of astronomers led by Eros Vanzella of the Astrophysics and Space Science Observatory of Bologna, Italy, inspected one such high-redshift, metal-poor and low-mass source. The source was identified behind the galaxy cluster Abell 2,744, which acts as a strong lens.

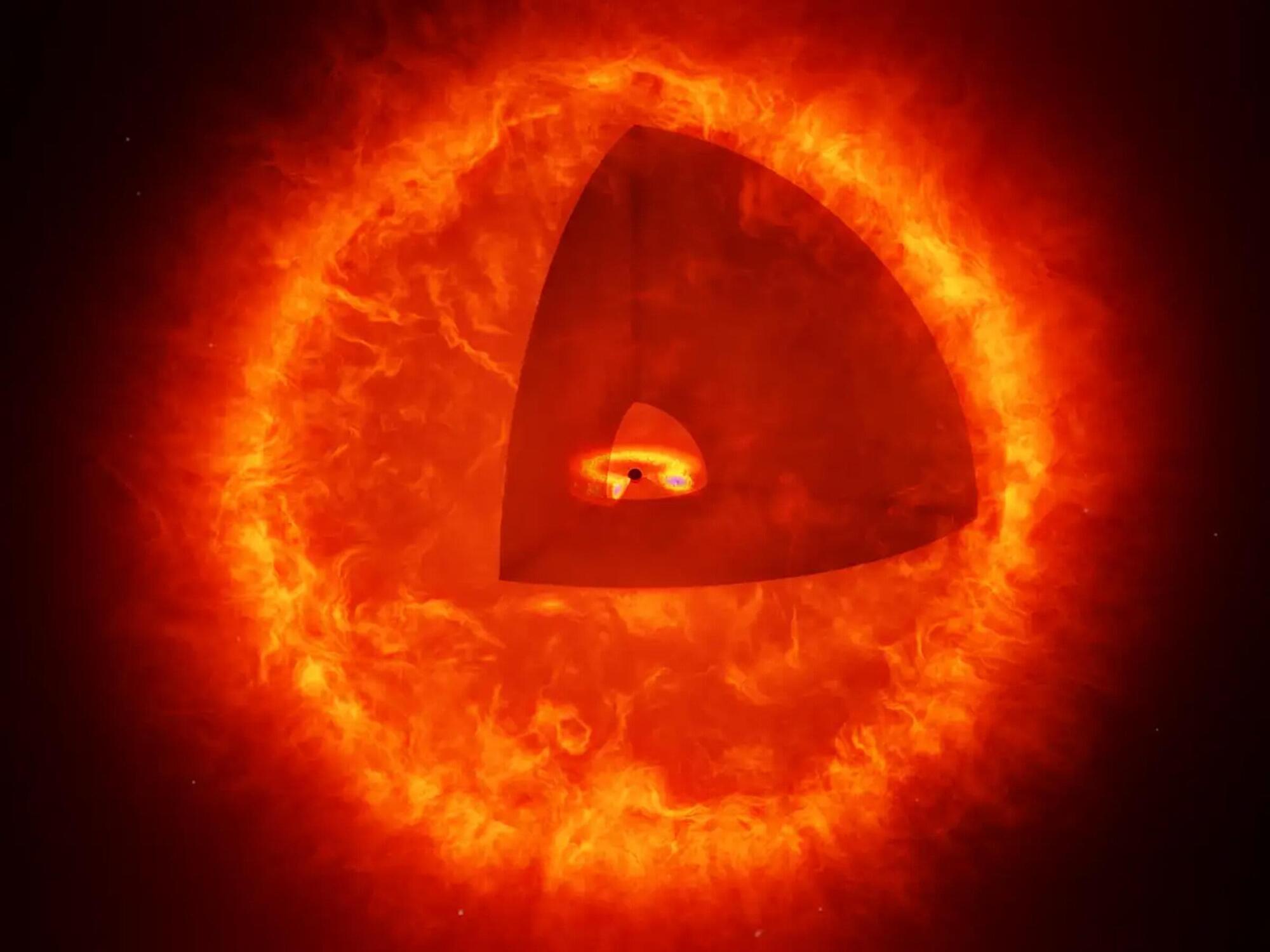

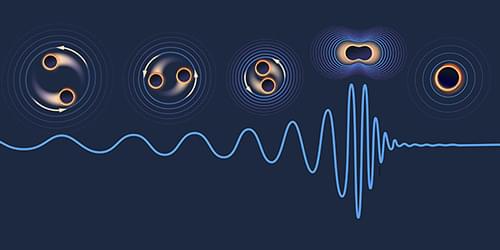

Ten years after scientists first detected gravitational waves emerging from two colliding black holes, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA collaboration, a research team that includes Columbia astronomy professor Maximiliano Isi, has recorded a signal from a nearly identical black hole collision.

Improvements in the detection technology allowed the researchers to see the black holes almost four times as clearly as they could a decade ago, and to confirm two important predictions: That merging black holes only ever grow or remain stable in size—as the late physicist Stephen Hawking predicted—and that, when disturbed, they ring like a bell, as predicted by Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

“This unprecedentedly clear signal of the black hole merger known as GW250114 puts to the test some of our most important conjectures about black holes and gravitational waves,” Isi said.

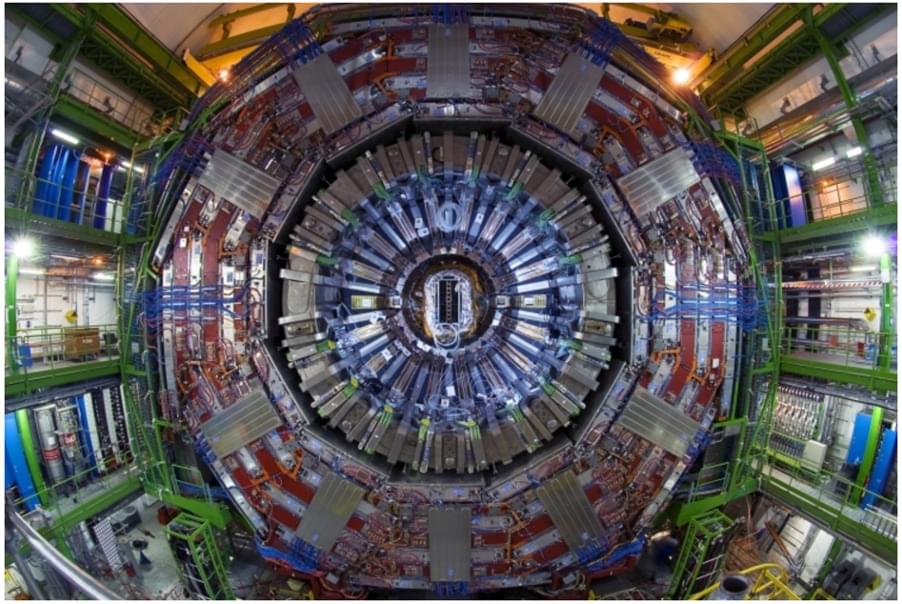

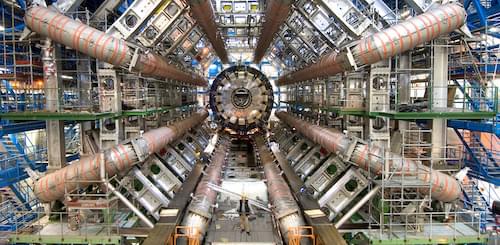

CMS scientists study the first-ever oxygen-oxygen collisions at the LHC, and observe signs of quarks and gluons losing energy when they travel through quark-gluon plasma – a state that existed just after the Big Bang.

When heavy ions such as lead (Pb) collide at nearly the speed of light inside the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), extreme conditions are created that can “melt” ordinary nuclear matter into a new state called the quark-gluon plasma (QGP). This hot and dense medium is believed to resemble the universe just microseconds after the Big Bang, when quarks and gluons – the fundamental building blocks of protons and neutrons – moved freely.

Physicists study the QGP medium by looking at how fast-moving quarks and gluons – collectively called partons – behave as they pass through it. Fast moving partons form sprays of particles, which can be seen as “jets” in particle detectors. In collisions of very small systems, such as proton-proton collisions, the observed jets are seen to retain the full energy or the original partons. In contrast, in heavy-ion collisions, the presence of the QGP medium leads to a significant loss of energy.

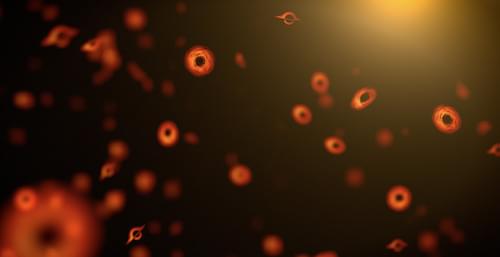

Tiny red objects spotted by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are offering scientists new insights into the origins of galaxies in the universe—and may represent an entirely new class of celestial object: a black hole swallowing massive amounts of matter and spitting out light.

Using the first datasets released by the telescope in 2022, an international team of scientists including Penn State researchers discovered mysterious “little red dots.” The researchers suggested the objects may be galaxies that were as mature as our current Milky Way, which is roughly 13.6 billion years old, just 500 to 700 million years after the Big Bang.

Informally dubbed “universe breakers” by the team, the objects were originally thought to be galaxies far older than anyone expected in the infant universe—calling into question what scientists previously understood about galaxy formation.

The clearest black hole merger signal ever measured has allowed researchers to test the Kerr nature of black holes and validate Stephen Hawking’s black hole area theorem.

Gravitational-wave astronomy is moving at breakneck speed. Just over a decade ago, the direct detection of gravitational waves was considered an elusive goal—perpetually said to be “five-to-ten years away.” Then came the 2015 breakthrough: the first observed merger of two black holes, known as GW150914 [1]. Detections have since become routine, with a catalog of black hole mergers now numbering in the hundreds. There is even evidence for a gravitational-wave background at nanohertz frequencies, plausibly sourced by a population of supermassive black hole binaries throughout the Universe. Now the LIGO detectors have captured the clearest merger signal ever recorded, GW250114 [2]. From such a signal, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) Collaboration was able to draw two spectacular conclusions. First, it confirmed that the nature of the merging objects is consistent with that of Kerr (spinning) black holes.

A deep neural network has proven essential in confirming a key prediction of one of the standard model’s cornerstones.

The Higgs mechanism explains why the electromagnetic and weak interactions have such drastically different strengths—that is, how their symmetry became broken a picosecond after the big bang. The Higgs does not interact with photons, rendering them massless, whereas they do interact with the carriers of the weak interaction (the W+, W–, and Z bosons), giving them masses of order 100 GeV. Their nonzero masses allow them to acquire a longitudinal polarization—that is, a spin orientation perpendicular to their direction of motion. Because of special relativity, photons and other massless bosons that travel at the speed of light can’t have longitudinal polarization, but the W and Z bosons and other massive particles can. If electroweak symmetry had been broken not by the Higgs mechanism but by a different interaction, there would be no Higgs boson to find.

Over the past decades, many research teams worldwide have been trying to detect dark matter, an elusive type of matter that does not emit, reflect or absorb light, using a variety of highly sensitive detectors. Ultimately, these detectors should be able to pick up the very small signals that would indicate the presence of dark matter or its weak interactions with regular matter.