Physicists are devising clever new ways to exploit the extreme sensitivity of gravitational wave detectors like LIGO. But so far, they’ve seen no signs of exotica.

Despite the fact that the Milky Way Galaxy happens to have hundreds of millions of black holes, we have been able to find only a dozen of them. The incognito nature of most black holes have frustrated astronomers as it not only makes it hard to research them but it also makes space a scary space.

These monstrous cosmic entities lurking in the dark could threaten our existence. Imagine how dangerous it would be to discover a gigantic bottomless pit, from which there is no escape, in our neighborhood?

And now we have discovered one of those monster black holes right out of our culdesac at a stone’s throw on the cosmic scale. Even the mere thought of something with such an intense gravitational force that even light cannot escape… so close to us is spine-chilling.

Welcome to Factnomenal, and today’s video talks about a massive black hole discovered in our galactic backyard.

Buy us a coffee to show your support!

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/Factnomenal.

DON’T CLICK THIS LINK: https://tinyurl.com/357shs3j.

Thanks for watching Factnomenal!

The latest findings are “the next big step towards the realization of neutrino astronomy.”

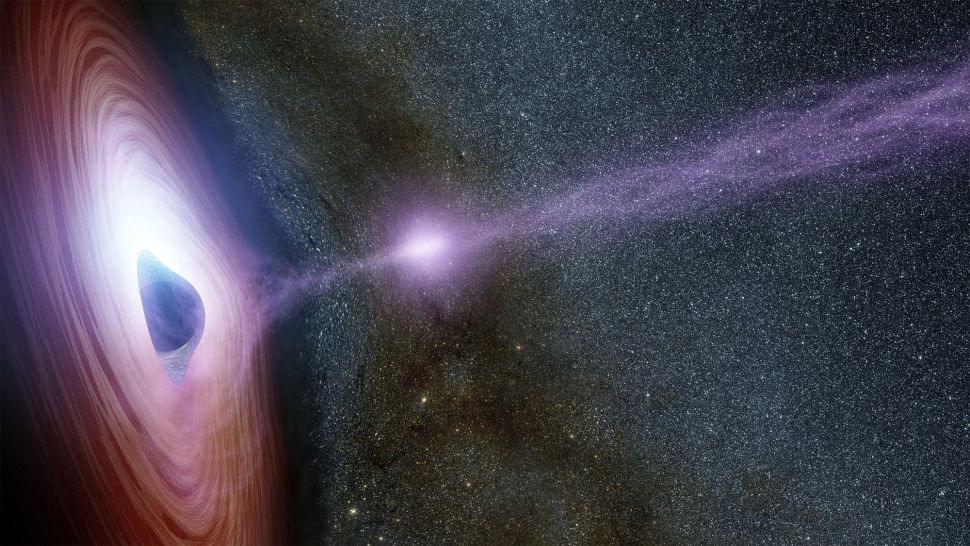

A black hole roughly 47 million light-years away, called NGC 1,068, is spewing out mysterious and elusive “ghost particles”, or neutrinos.

Neutrinos are notoriously difficult to detect as they require precise instruments deep below the Earth’s surface to avoid any interference from cosmic rays and background radiation.

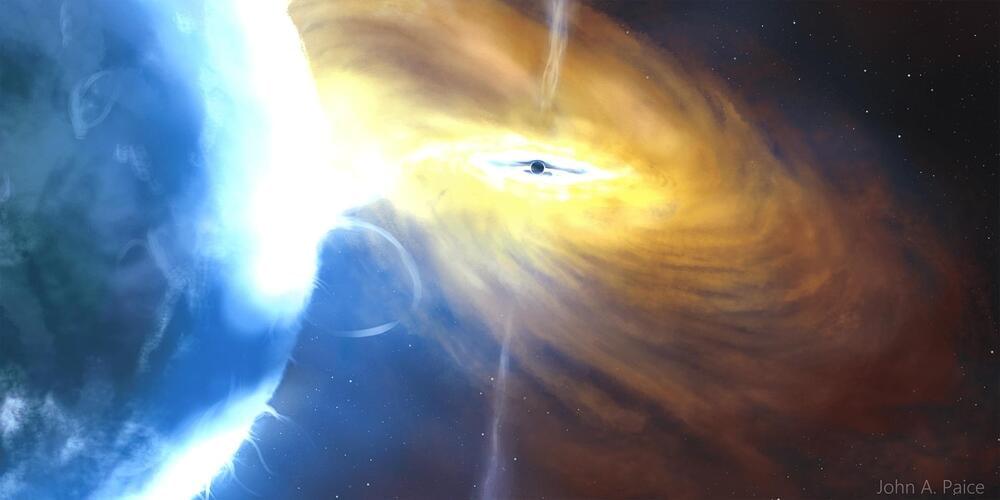

In 1961 astronomers discovered a powerful x-ray source coming from the constellation Cygnus. Not knowing what it was, they named the source Cygnus X-1. It’s one of the strongest x-ray sources in the sky, and we now know it is powered by a stellar-mass black hole. Since it is only about 7,000 light-years away, it also gives astronomers an excellent view of how stellar-mass black holes behave. Even after six decades of study, it continues to teach us a few things, as a recent study in Science shows.

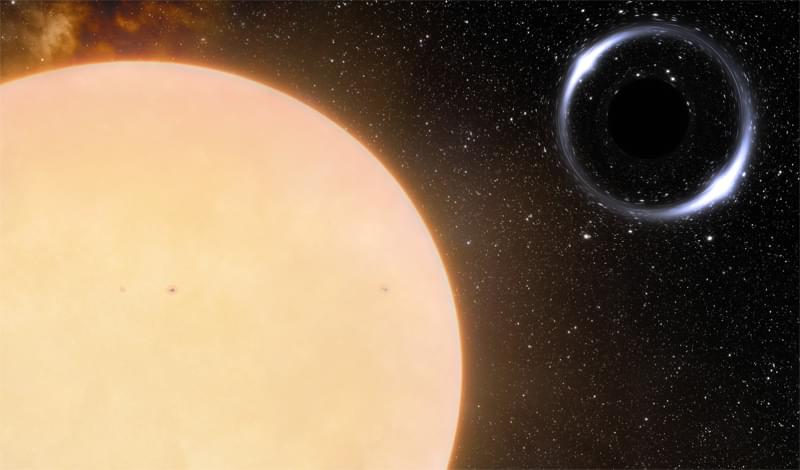

Cygnus X-1 is actually a binary system. The black hole itself is a 21 solar-mass stellar remnant, and it orbits a 41 solar-mass companion star. It’s a powerful x-ray source because material from the star is captured into an accretion disk of the black hole, which superheats the material and generates jets of plasma that flow away from the black hole. This is a common situation for black holes, but astronomers still don’t understand all the details of how this type of structure evolves.

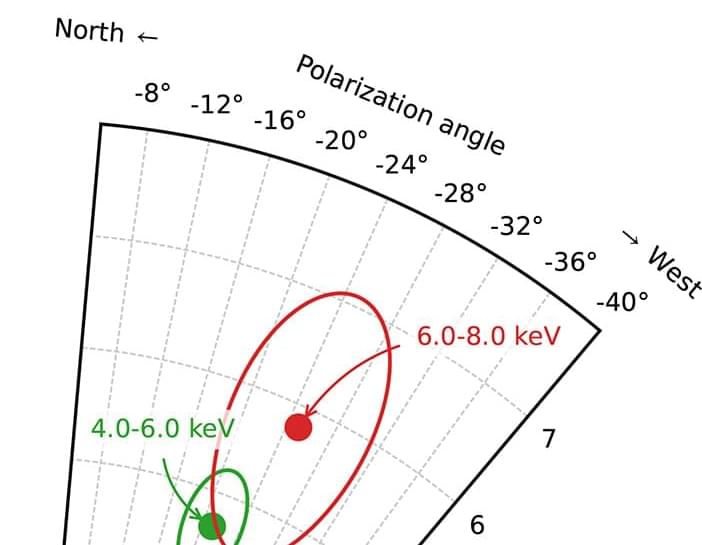

For this study, the team used data from the Imaging X-Ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE), which can capture not just x-rays but also their polarization. When they combined this data with other observations of Cygnus X-1, they found the x-rays are emitted not from the regions along the jets, but from a 2,000 km region perpendicular to the jets. In other words, the accretion disk itself is the primary x-ray source. This supports the model where the innermost region of the accretion disk is what powers a black hole’s jets.

You can imagine starting at the beginning, evolving the Universe forward according to the laws of physics, and measuring those earliest signals and their imprints on the Universe to determine how it has expanded over time. Alternatively, you can imagine starting here and now, looking out at the distant objects as we see them receding from us, and then drawing conclusions as to how the Universe has expanded from that.

Both of these methods rely on the same laws of physics, the same underlying theory of gravity, the same cosmic ingredients, and even the same equations as one another. And yet, when we actually perform our observations and make those critical measurements, we get two completely different answers that don’t agree with one another. This is, in many ways, the most pressing cosmic conundrum of our time. But there’s still a possibility that no one is mistaken and everyone is doing the science right. The entire controversy over the expanding Universe could go away if just one new thing is true: if there was some form of “early dark energy” in the Universe. Here’s why so many people are compelled by the idea.

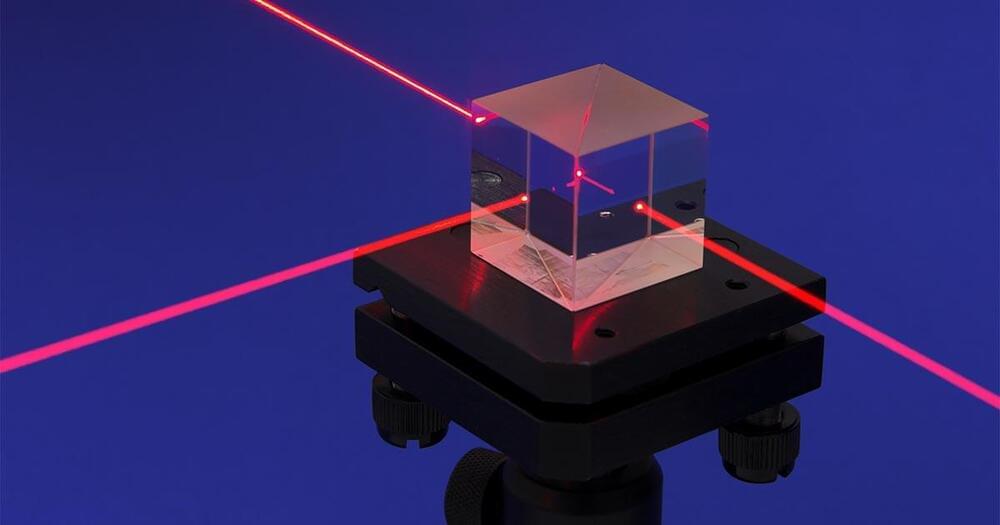

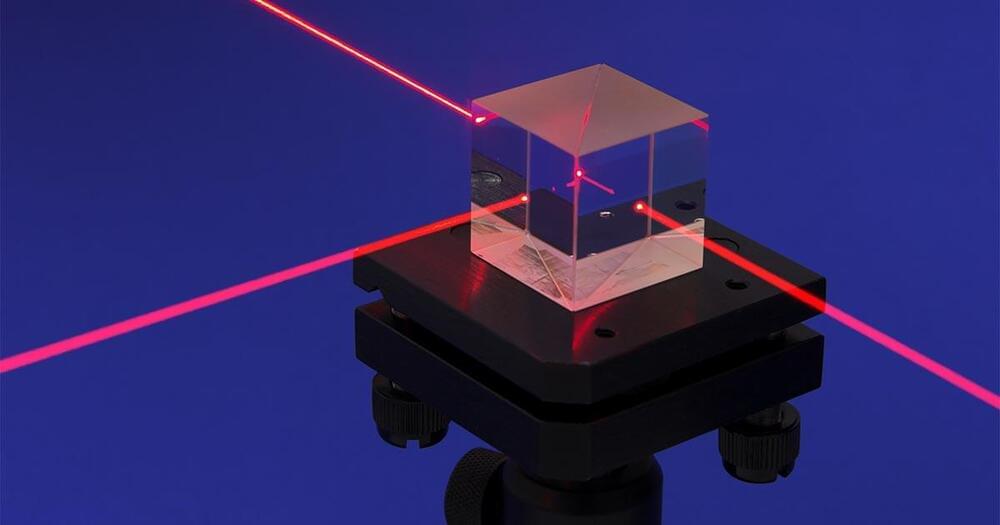

Researchers from Australia and Singapore are working on a new quantum technique that could enhance optical VLBI. It’s known as Stimulated Raman Adiabatic Passage (STIRAP), which allows quantum information to be transferred without losses. When imprinted into a quantum error correction code, this technique could allow for VLBI observations into previously inaccessible wavelengths. Once integrated with next-generation instruments, this technique could allow for more detailed studies of black holes, exoplanets, the Solar System, and the surfaces of distant stars.

The interferometry technique consists of combining light from multiple telescopes to create images of an object that would otherwise be too difficult to resolve. Very Long Baseline Interferometry refers to a specific technique used in radio astronomy where signals from an astronomical radio source (black holes, quasars, pulsars, star-forming nebulae, etc.) are combined to create detailed images of their structure and activity. In recent years, VLBI has yielded the most detailed images of the stars that orbit Sagitarrius A* (Sgr A•, the SMBH at the center of our galaxy.

For the better part of a century, quantum physics and the general theory of relativity have been a marriage on the rocks. Each perfect in their own way, the two just can’t stand each other when in the same room.

Now a mathematical proof on the quantum nature of black holes just might show us how the two can reconcile, at least enough to produce a grand new theory on how the Universe works on cosmic and microcosmic scales.

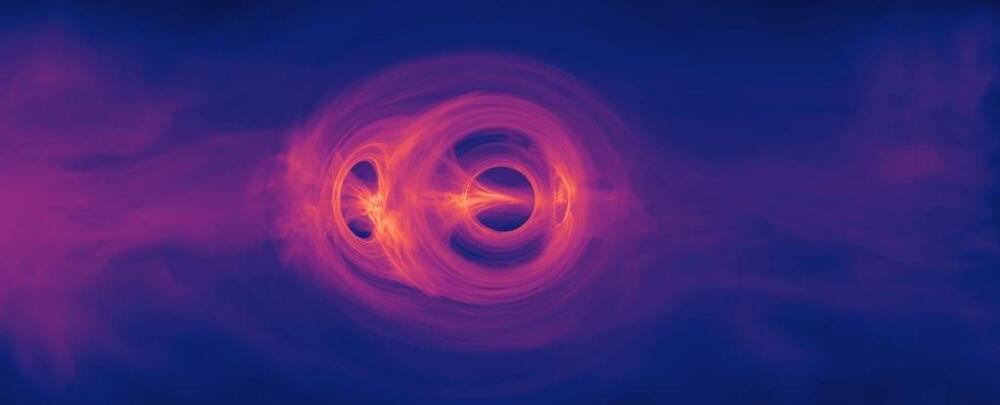

A team of physicists has mathematically demonstrated a weird quirk concerning how these mind-bendingly dense objects might exist in a state of quantum superposition, simultaneously occupying a spectrum of possible characteristics.

For those of us who have done a bit of homework on space, and have a basic understanding of the properties of light and gravity, we may feel like have a lot of the answers. These two things have a huge impact on the known universe, as well as our conception of it.

However, the interaction of these two fundamental aspects of space gets a bit confusing.

We have heard adages like nothing can escape the gravitational pull of a black hole, and we often think of black holes as cosmic vacuum cleaners that can suck up entire galaxies and anything else that has mass. We also think of light as being composed of massless photons, and as the fastest-moving thing in the universe – moving at roughly 300,000 km/second.

O.o!!!

A black hole x-ray binary (XRB) system forms when gas is stripped from a normal star and accretes onto a black hole, which heats the gas sufficiently to emit x-rays. We report a polarimetric observation of the XRB Cygnus X-1 using the Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer. The electric field position angle aligns with the outflowing jet, indicating that the jet is launched from the inner x-ray emitting region. The polarization degree is 4.01 ± 0.20% at 2 to 8 kiloelectronvolts, implying that the accretion disk is viewed closer to edge-on than the binary orbit. The observations reveal that hot x-ray emitting plasma is spatially extended in a plane perpendicular to the jet axis, not parallel to the jet.