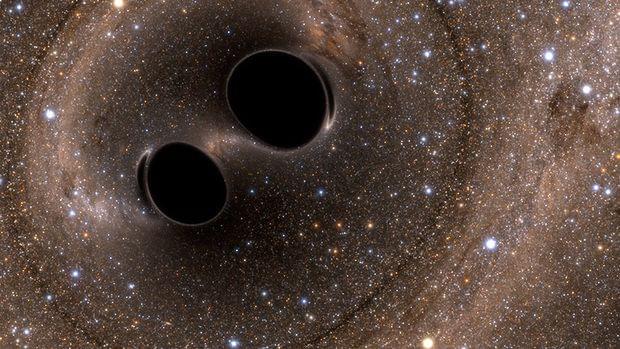

Scientists have discovered gravitational waves stemming from a black hole merger event that suggest the resultant black hole settled into a stable, spherical shape. These waves also reveal the combo black hole may be much larger than previously thought.

When initially detected on May 21, 2019, the gravitational wave event known as GW190521 was believed to have come from a merger between two black holes, one with a mass equivalent to just over 85 suns and the other with a mass equivalent to about 66 suns. Scientists believed the merger therefore created an approximately 142 solar mass daughter black hole.

Yet, newly studied spacetime vibrations from the merger-created black hole, rippling outward as the void resolved into a proper spherical shape, seem to suggest it’s more massive than initially predicted. Rather than possess 142 solar masses, calculations say it should have a mass equal to around 250 times that of the sun.