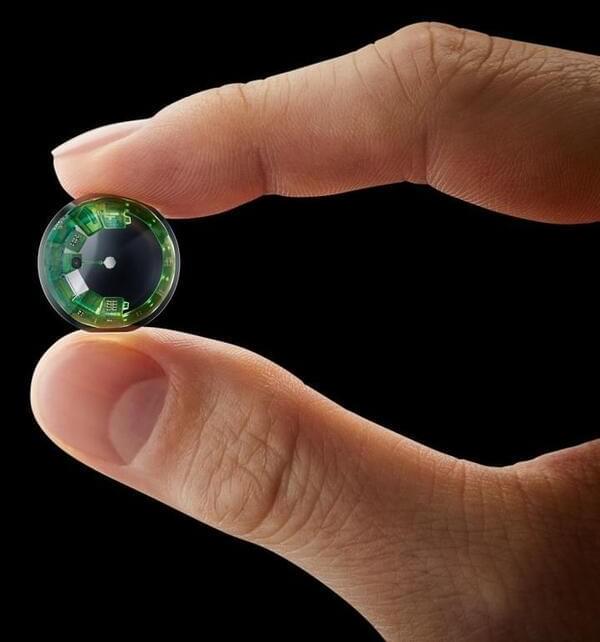

It’s a reference to the evil form in the ‘Lord of the Rings’ books. For those unfamiliar with the ‘Lord of the Rings” books and movies, the Eye of Sauron is the chief antagonist in the series, exemplified as a flaming eye and that is a metaphor for pure evil. It’s not something anyone would want to be compared to unless, of course, you are Meta founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

Mark Zuckerberg on Long-Term Strategy, Business and Parenting Principles, Personal Energy Management, Building the Metaverse, Seeking Awe, the Role of Religion, Solving Deep Technical Challenges (e.g., AR), and More | Brought to you by Eight Sleep’s Pod Pro Cover sleeping solution for dynamic cooling and heating (http://eightsleep.com/Tim), Magic Spoon delicious low-carb cereal (http://magicspoon.com/tim), and Helium 10 all-in-one software suite to sell on Amazon (https://helium10.com/tim).

Mark Zuckerberg (FB/IG) is the founder, chairman, and CEO of Meta, which he originally founded as Facebook in 2004. Mark is responsible for setting the overall direction and product strategy for the company. In October 2021, Facebook rebranded to Meta to reflect all of its products and services across its family of apps and a focus on developing social experiences for the metaverse—moving beyond 2D screens toward immersive experiences like augmented and virtual reality to help build the next evolution in social technology.

He is also the co-founder and co-CEO of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative with his wife Priscilla, which is leveraging technology to help solve some of the world’s toughest challenges—including supporting the science and technology that will make it possible to cure, prevent, or manage all diseases by the end of the twenty-first century.

Mark studied computer science at Harvard University before moving to Palo Alto, California, in 2004.