Smartphone sales have had their worst quarterly performance in over a decade, a fact that raises two big questions. Have the latest models finally bored the market with mere incremental improvements? And if they have, what will the next form factor (and function) be? Today a deep tech startup called Xpanceo is announcing $40 million in funding from a single investor, Opportunity Ventures in Hong Kong, to pursue its take on one of the possible answers to that question: computing devices in the form of smart contact lenses.

The company wants to make tech more simple, and it believes the way to do that is to make it seamless and more connected to how we operate every day. “All current computers will be obsolete [because] they’re not interchangeable,” said Roman Axelrod, who co-founded the startup with material scientist and physicist Valentyn S. Volkov. “We are enslaved by gadgets.”

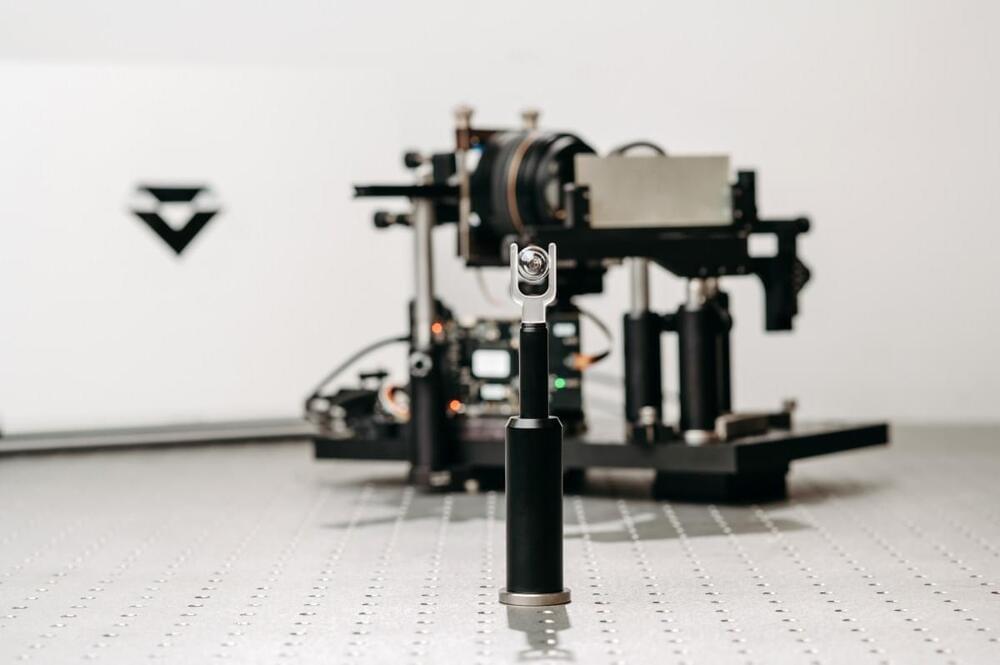

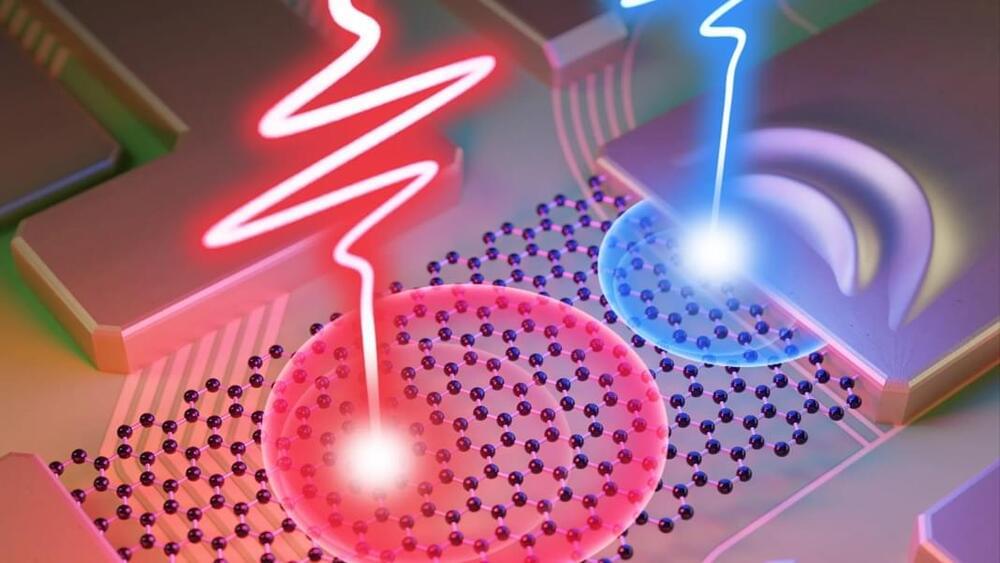

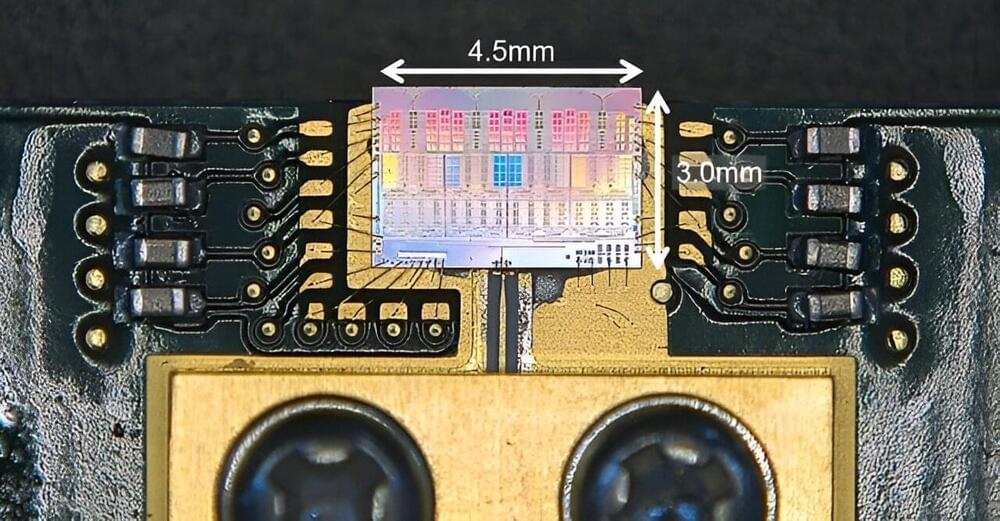

With a focus on new materials and moving away from silicon-based processing and towards new approaches to using optoelectronics, Xpanceo’s modest ambition, Axelrod said in an interview, is to “merge all the gadgets into one, to provide humanity with a gadget with an infinite screen. What we aim for is to create the next generation of computing.”