Researchers believe dark rocks at the site of a future Mars rover landing mission may be left over from ancient volcanic eruptions, and may be protecting signs of life — if there ever was life on Mars.

There is more research than ever focused on reflecting sunlight away from the planet to cool the climate – but there are still far more questions than answers about the effects.

There’s a good chance you owe your existence to the Haber-Bosch process.

This industrial chemical reaction between hydrogen and nitrogen produces ammonia, the key ingredient in synthetic fertilizers that supply much of the world’s food supply and enabled the population explosion of the last century.

It may also threaten the existence of future generations. The process consumes about 2% of the world’s total energy supply, and the hydrogen required for the reaction mostly comes from fossil fuels.

Amazon announced a major milestone in its electric vehicle transition, officially bringing 20,000 Rivian EDVs (electric delivery vans) into its fleet.

Back in 2019, Amazon announced its Climate Pledge to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2040. Part of the Pledge included a partnership with Rivian for 100,000 all-electric delivery vehicles. The goal was to have all EDVs on the road and in the Amazon fleet by 2030.

The first Amazon-Rivian EDV hit the road in 2022, and since then, the vans have made it to thousands of locations across the United States.

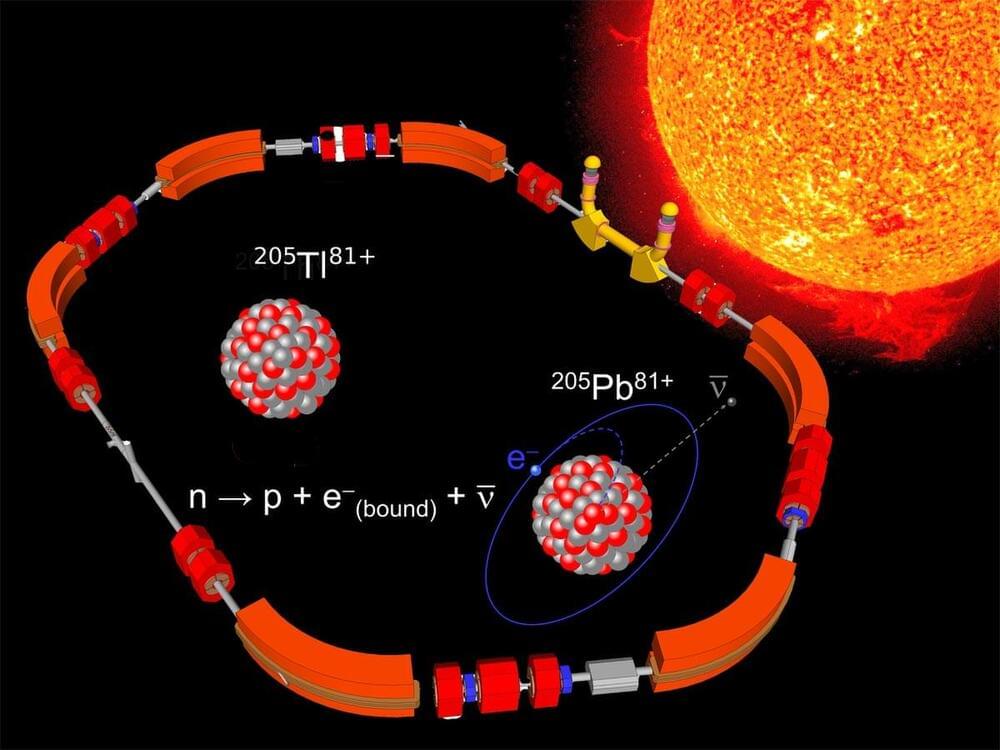

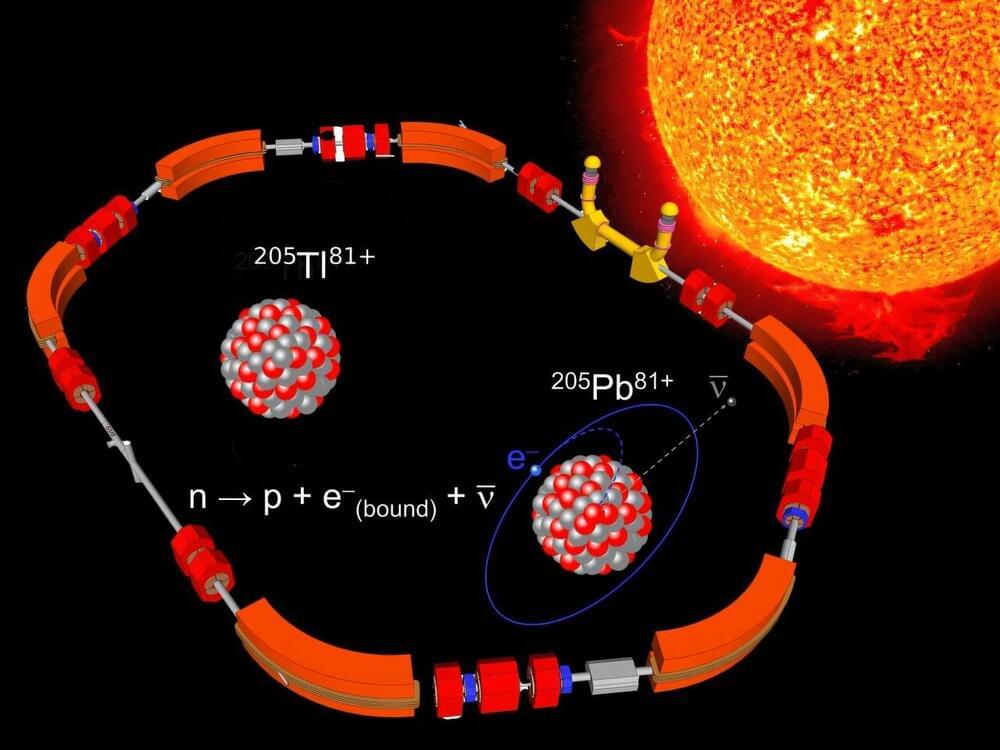

The LOREX experiment utilizes lorandite ore to gauge historical solar neutrino flux, revealing insights about the Sun’s development and climatic effects through advanced decay rate measurements.

The Sun, Earth’s life-sustaining powerhouse, generates immense energy through nuclear fusion while emitting a steady stream of neutrinos — subatomic particles that reveal its inner workings. While modern neutrino detectors shed light on the Sun’s current behavior, key questions remain about its stability over millions of years — a timeframe encompassing human evolution and major climate changes.

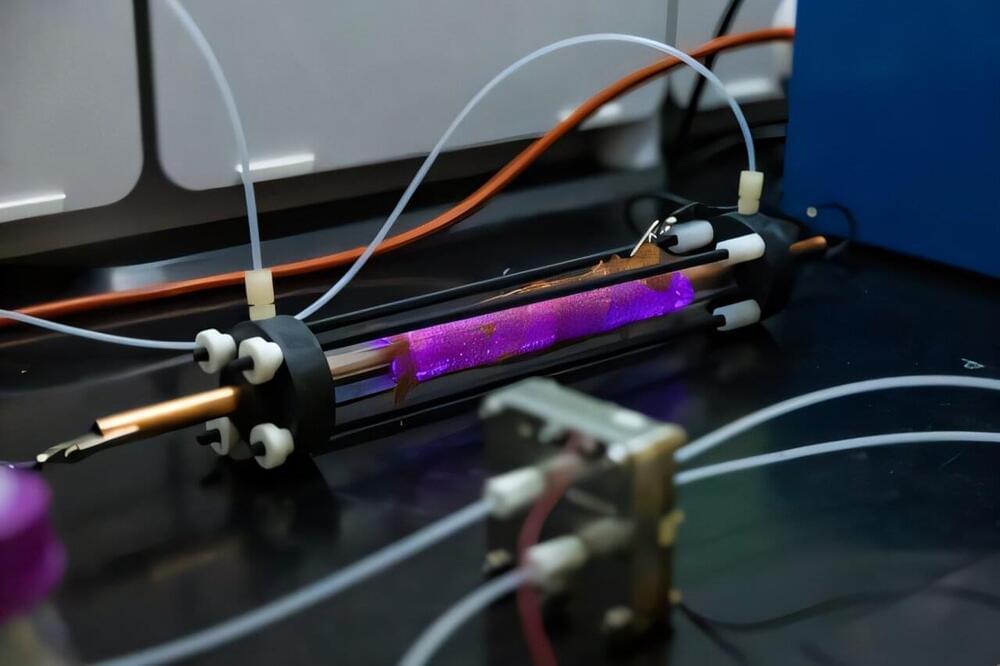

Addressing these questions is the mission of the LORandite EXperiment (LOREX), which depends on accurately determining the solar neutrino cross-section for thallium. An international team of scientists has now achieved this crucial measurement using the unique Experimental Storage Ring (ESR) at GSI/FAIR in Darmstadt. Their groundbreaking results, advancing our understanding of the Sun’s long-term stability, have been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Researchers at MIT are developing innovative agricultural technologies such as stress-signaling plants, microbial fertilizers, and protective seed coatings to adapt farming to climate change and enhance food security.

With global temperatures on the rise, agricultural practices must adapt to new challenges. Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of droughts, and some land may no longer be arable. Additionally, it is becoming increasingly difficult to feed an ever-growing population without expanding the production of fertilizer and other agrochemicals, which have a large carbon footprint that is contributing to global warming.

Now, scientists across MIT are tackling these issues from a variety of angles, including the development of plants that sound an alarm when they’re under stress and making seeds more resilient to drought. These technologies, and more yet to be devised, will be essential to feed the world’s population as the climate changes.

High overhead, there is a layer of the atmosphere called the mesosphere. It is located roughly 31 to 55 miles above ground.

The mesosphere might seem pretty far removed from everyday concerns. Still, it can be disturbed by severe weather far below.

On the day Helene hit, NASA’s instruments captured signs of a type of atmospheric wave, not related to the space-time ones Einstein predicted, but rather ones formed by events like hurricanes.

The sun, the essential engine that sustains life on Earth, generates its tremendous energy through the process of nuclear fusion. At the same time, it releases a continuous stream of neutrinos—particles that serve as messengers of its internal dynamics. Although modern neutrino detectors unveil the sun’s present behavior, significant questions linger about its stability over periods of millions of years—a timeframe that spans human evolution and significant climate changes.

Finding answers to this is the goal of the LORandite EXperiment (LOREX) that requires a precise knowledge of the solar neutrino cross section on thallium. This information has now been provided by an international collaboration of scientists using the unique facilities at GSI/FAIR’s Experimental Storage Ring ESR in Darmstadt to obtain an essential measurement that will help to understand the long-term stability of the sun. The results of the measurements have been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

LOREX is the only long-time geochemical solar neutrino experiment still actively pursued. Proposed in the 1980s, it aims to measure solar neutrino flux averaged over a remarkable four million years, corresponding to the geological age of the lorandite ore.

How can tree placement impact urban temperatures? This is what a recent study published in Communications Earth & Environment hopes to address as an international team of researchers investigated how tree planting locations plays a vital role in mitigating the effects of climate change on urban environments. This study holds the potential to help researchers, climate scientists, the public, and city planners have the necessary tools and resources to combat climate change while still providing adequate ecology for their surroundings.

For the study, the researchers conducted a literature review on 182 past studies discussing how tree planting can decrease temperatures in urban environments, including 110 cities or regions worldwide and 17 climates, with the goal of quantifying this temperature decrease on a global scale. In the end, the team found that 83 percent of the cities used in the study experienced average monthly peak temperatures below 26 degrees Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit) while also noting that tree planting contributes to a decrease of 12 degrees Celsius (54 degrees Fahrenheit) in pedestrian-level temperatures.

“Our study provides context-specific greening guidelines for urban planners to more effectively harness tree cooling in the face of global warming,” said Dr. Ronita Bardhan, who is an Associate Professor of Sustainable Built Environment at the University of Cambridge and a co-author on the study. “Our results emphasize that urban planners not only need to give cities more green spaces, they need to plant the right mix of trees in optimal positions to maximize cooling benefits.”

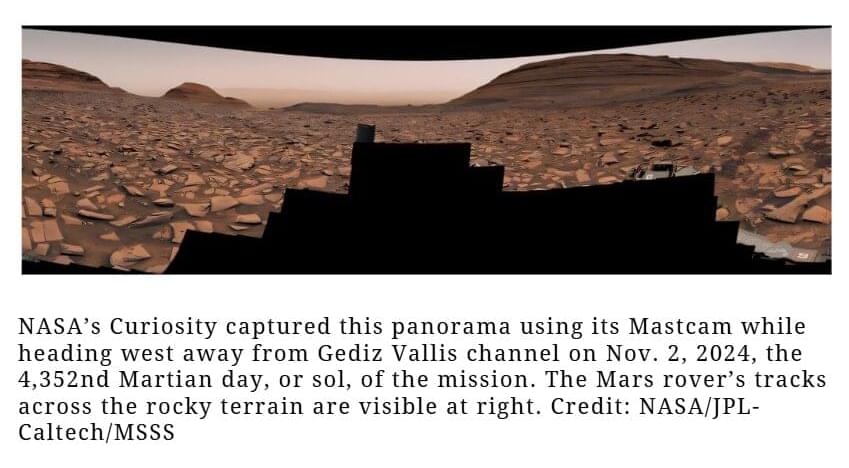

NASA’s Curiosity rover is preparing for the next leg of its journey, a months-long trek to a formation called the boxwork, a set of weblike patterns on Mars’s surface that stretches for miles. It will soon leave behind Gediz Vallis channel, an area wrapped in mystery. How the channel formed so late during a transition to a drier climate is one big question for the science team. Another mystery is the field of white sulfur stones the rover discovered over the summer.

Curiosity imaged the stones, along with features from inside the channel, in a 360-degree panorama before driving up to the western edge of the channel at the end of September.

The rover is searching for evidence that ancient Mars had the right ingredients to support microbial life, if any formed billions of years ago, when the Red Planet held lakes and rivers. Located in the foothills of Mount Sharp, a 3-mile-tall (5-kilometer-tall) mountain, Gediz Vallis channel may help tell a related story: what the area was like as water was disappearing on Mars. Although older layers on the mountain had already formed in a dry climate, the channel suggests that water occasionally coursed through the area as the climate was changing.