A team of chemists at the University of Cambridge has developed a powerful new method for adding single carbon atoms to molecules more easily, offering a simple one-step approach that could accelerate drug discovery and the design of complex chemical products.

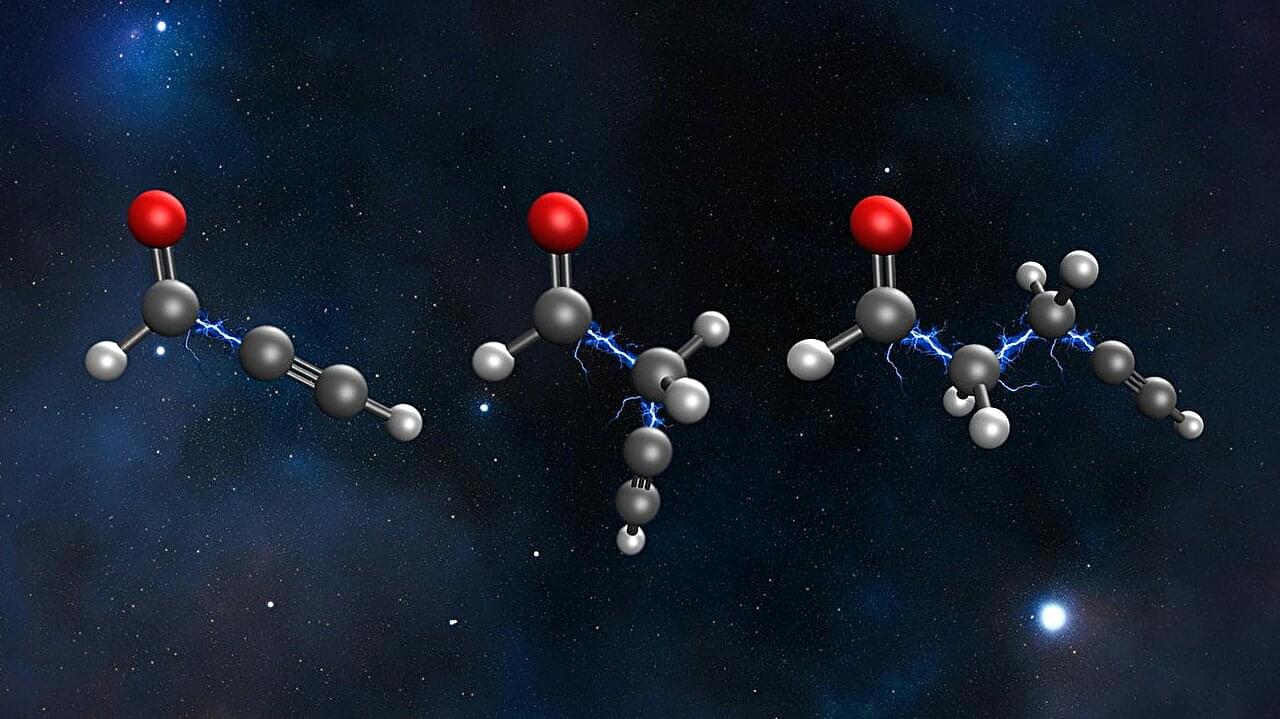

The research, recently published in the journal Nature under the title “One-carbon homologation of alkenes,” unveils a breakthrough method for extending molecular chains—one carbon atom at a time. This technique targets alkenes, a common class of molecules characterized by a double bond between two carbon atoms. Alkenes are found in a wide range of everyday products, from anti-malarial medicines like quinine to agrochemicals and fragrances.

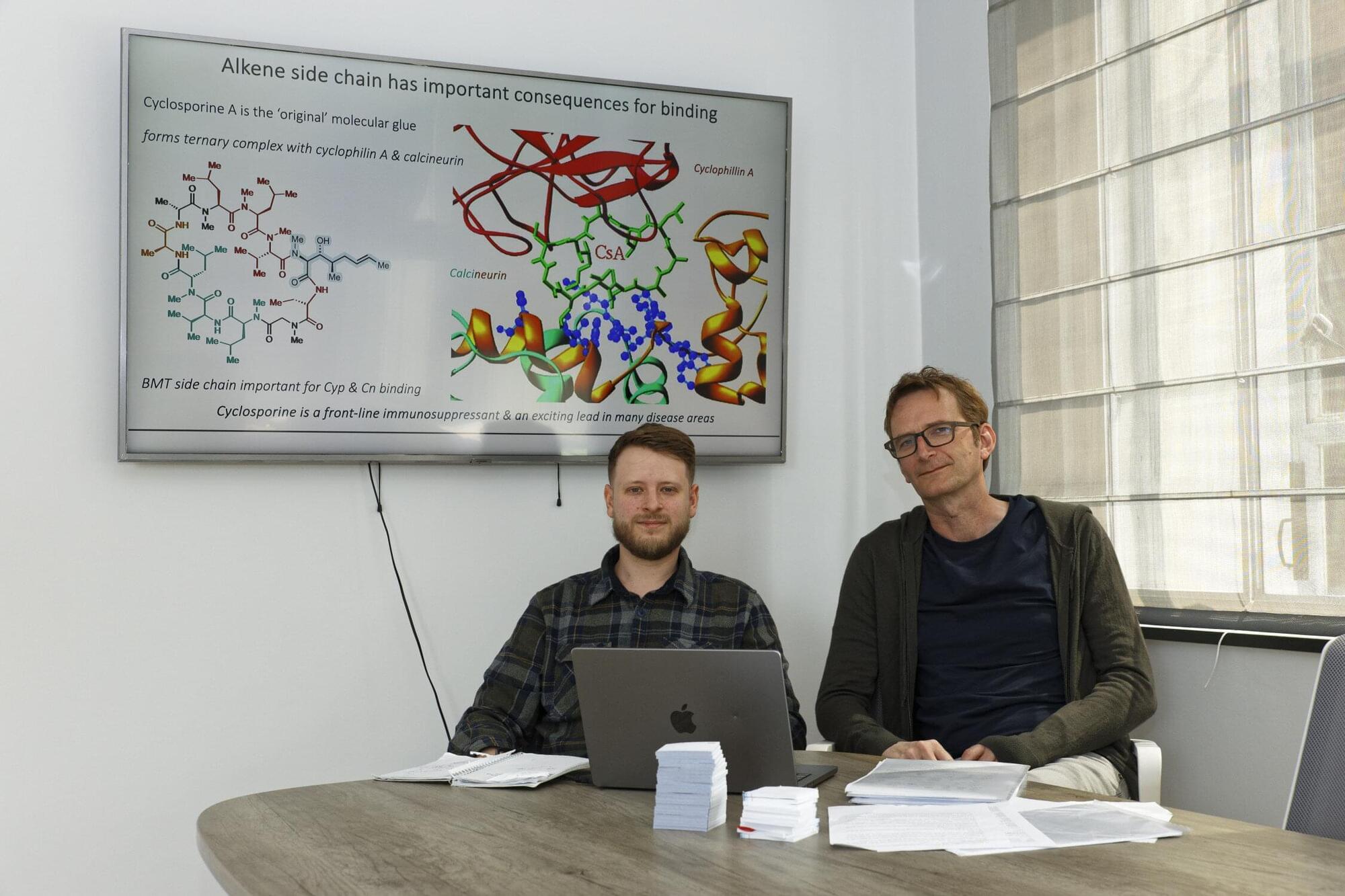

Led by Dr. Marcus Grocott and Professor Matthew Gaunt from the Yusuf Hamied Department of Chemistry at the University of Cambridge, the work replaces traditional multi-step procedures with a single-pot reaction that is compatible with a wide range of molecules.