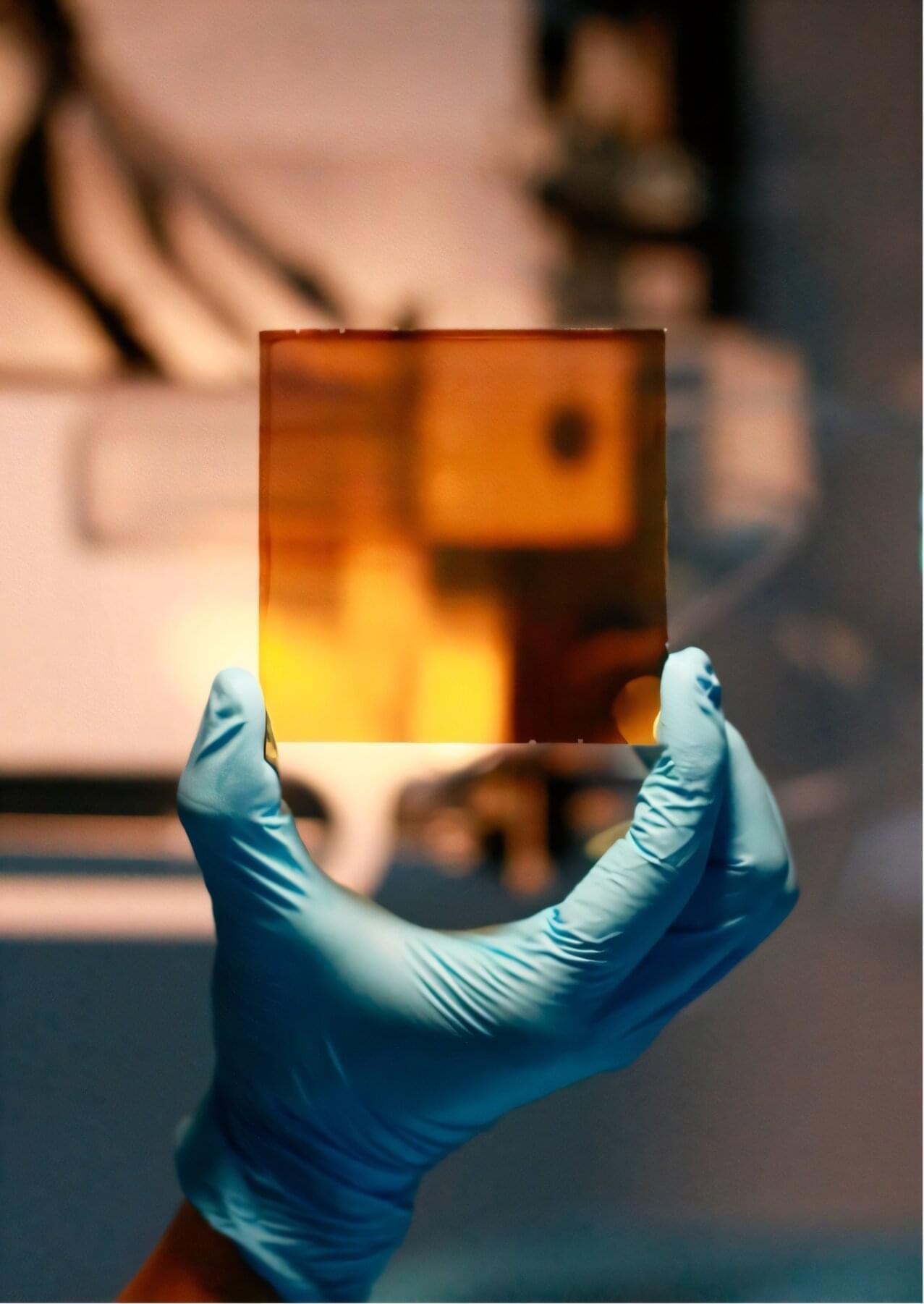

University of Queensland researchers have set a world record for solar cell efficiency with eco-friendly perovskite technology. A team led by Professor Lianzhou Wang has unveiled a tin halide perovskite (THP) solar cell capable of converting sunlight to electricity at a certified record efficiency of 16.65%. The research is published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Working across UQ’s Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology and the School of Chemical Engineering, Professor Wang said the certified reading achieved by his lab was nearly one percentage point higher than the previous best for THP solar cells.

“It might not seem like much, but this is a giant leap in a field that is renowned for delicate and incremental progress,” Professor Wang said.