Vibrations are everywhere—from the hum of machinery to the rumble of transport systems. Usually, these random motions are wasted and dissipated without producing any usable work.

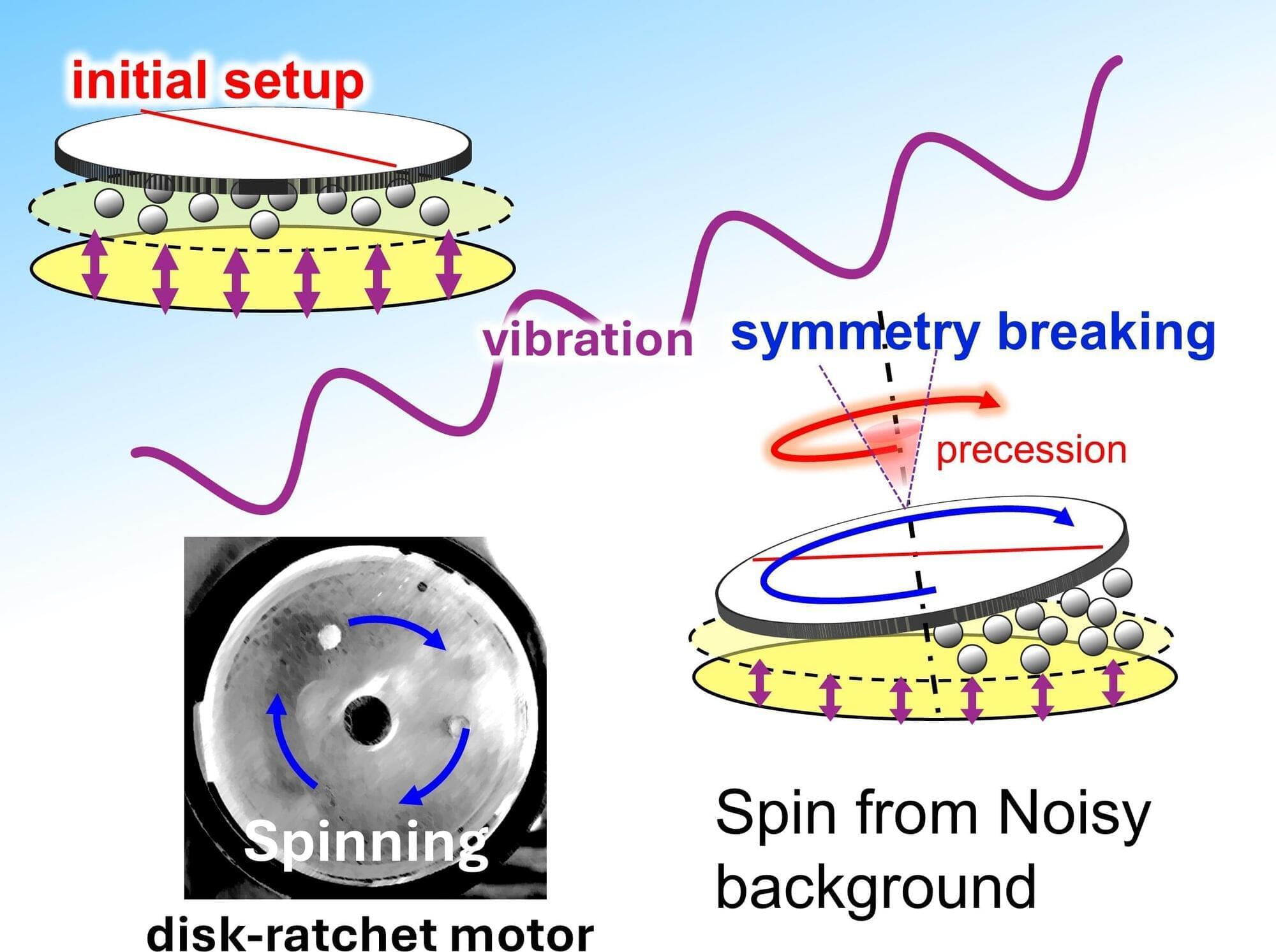

Recently, scientists have been fascinated by “ratchet systems,” which are mechanical systems that rectify chaotic vibrations into directional motion. In biology, molecular motors achieve this feat within living cells to drive the essential processes by converting random molecular collisions into purposeful motions. However, at a large scale, these ratchet systems have always relied on built-in asymmetry, such as gears or uneven surfaces.

Moving beyond this reliance on asymmetry, a team of researchers led by Ms. Miku Hatatani, a Ph.D. student at the Graduate School of Science and Engineering, along with Mr. Junpei Oguni, graduate school alumnus at the Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Professor Daigo Yamamoto and Professor Akihisa Shioi from the Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science at Doshisha University, demonstrate the world’s first symmetric ratchet motor.