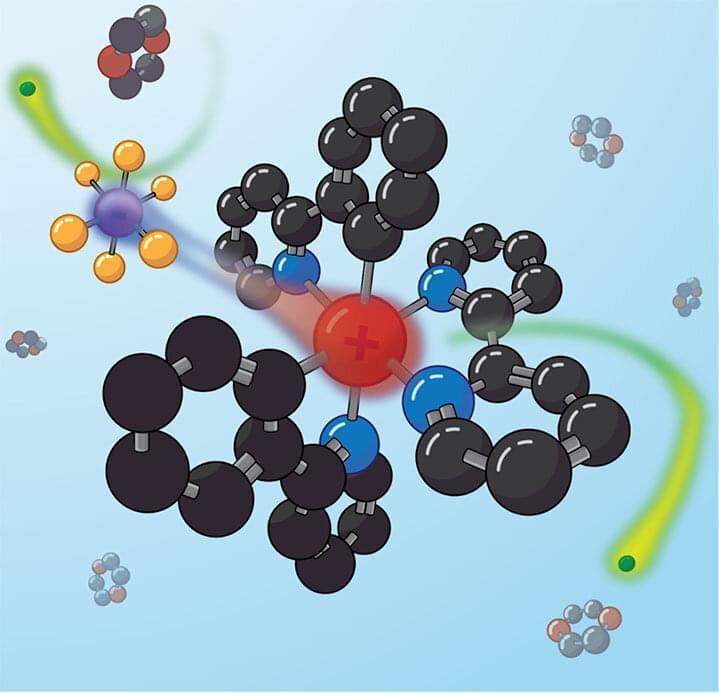

U.S. and European physicists have demonstrated a new method for predicting whether metallic compounds are likely to host topological states that arise from strong electron interactions.

Physicists from Rice University, leading the research and collaborating with physicists from Stony Brook University, Austria’s Vienna University of Technology (TU Wien), Los Alamos National Laboratory, Spain’s Donostia International Physics Center and Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids, unveiled their new design principle in a study published online today in Nature Physics.

The team includes scientists at Rice, TU Wien and Los Alamos who discovered the first strongly correlated topological semimetal in 2017. That system and others the new design principle seeks to identify are broadly sought by the quantum computing industry because topological states have immutable features that cannot be erased or lost to quantum decoherence.