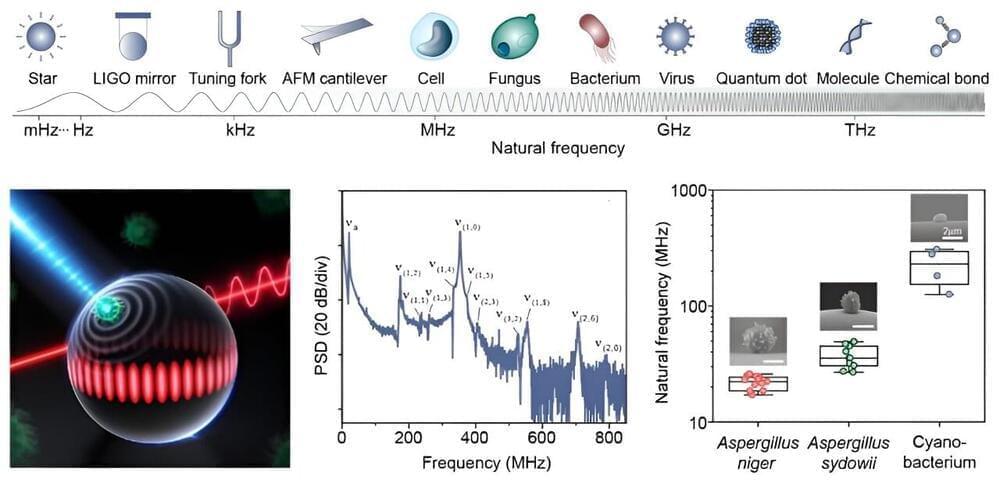

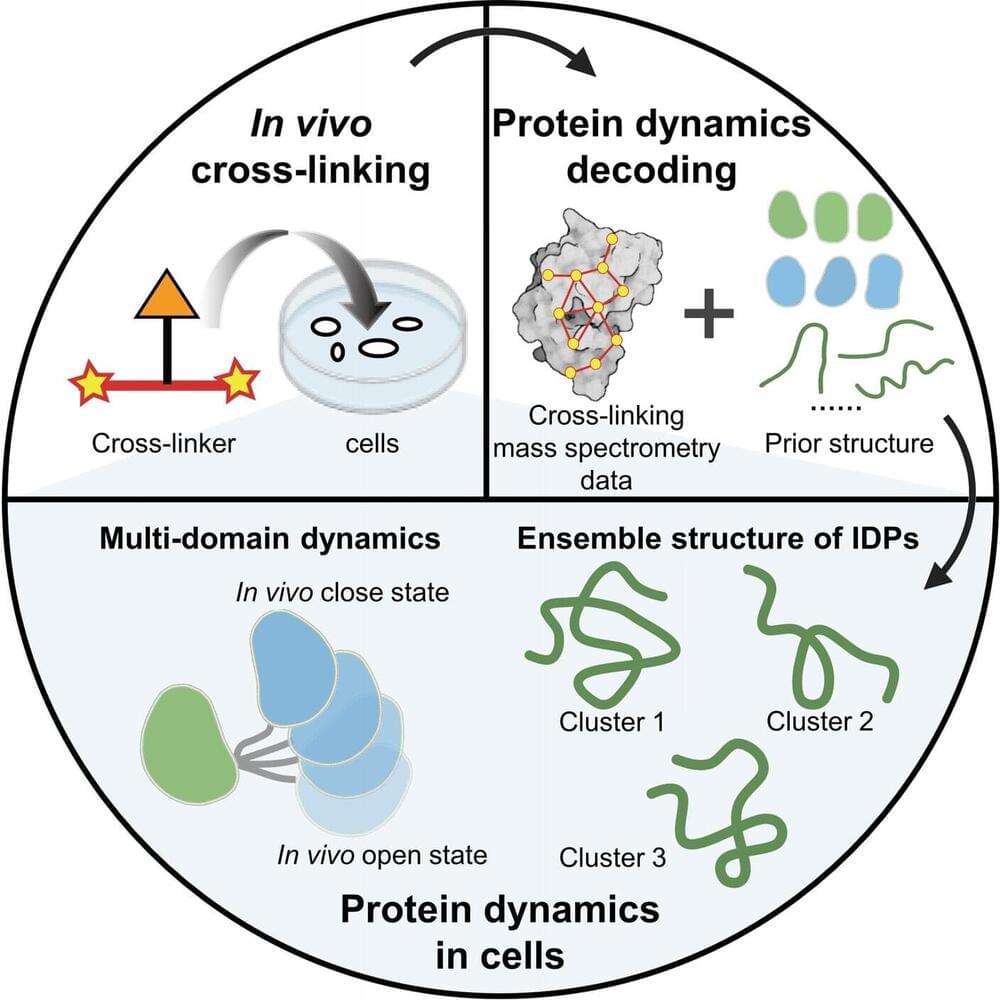

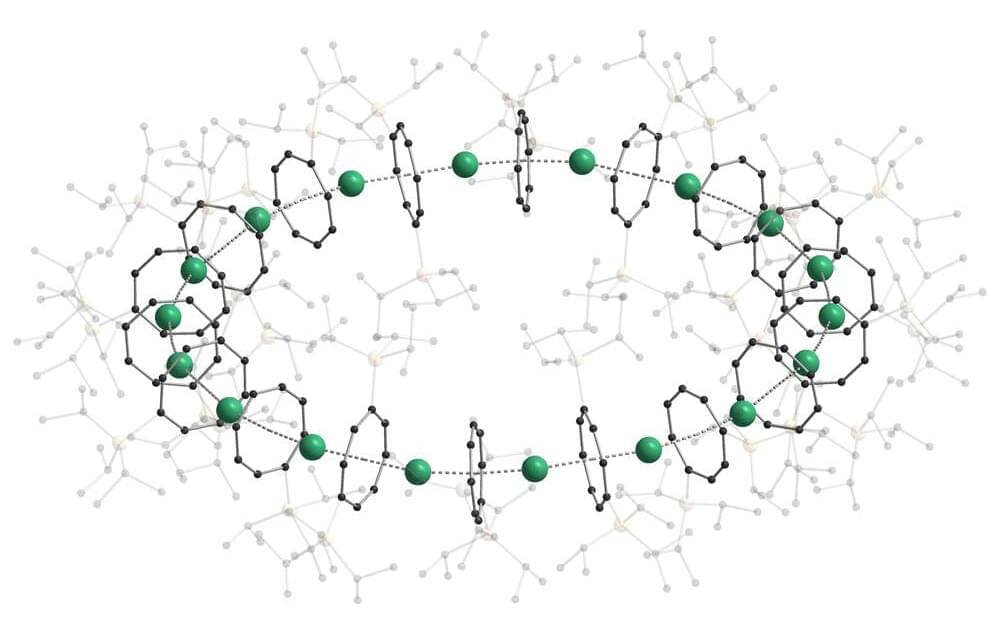

Weird things happen on the quantum level. Whole clouds of particles can become entangled, their individuality lost as they act as one.

Now scientists have observed, for the first time, ultracold atoms cooled to a quantum state chemically reacting as a collective, rather than haphazardly forming new molecules after bumping into each other by chance.

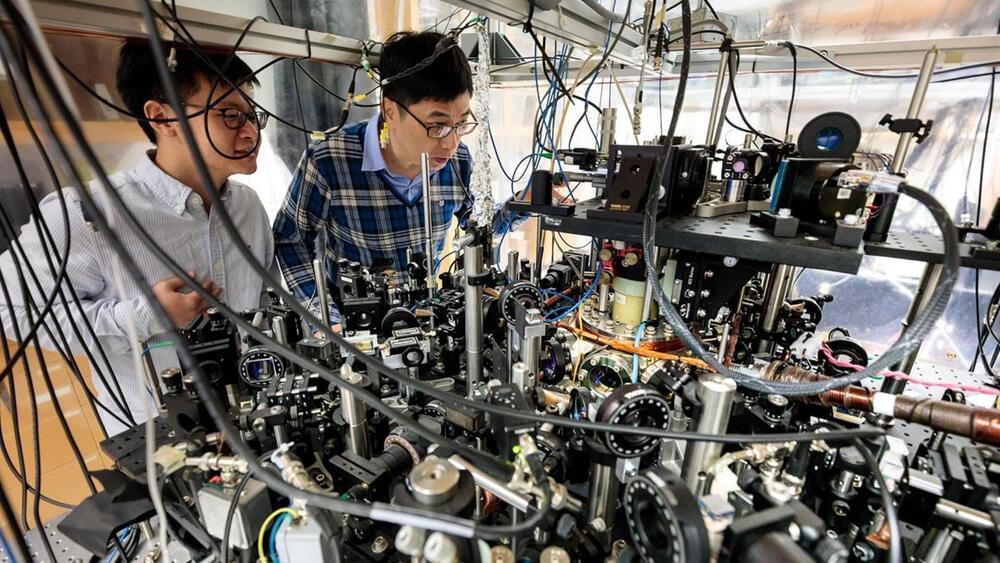

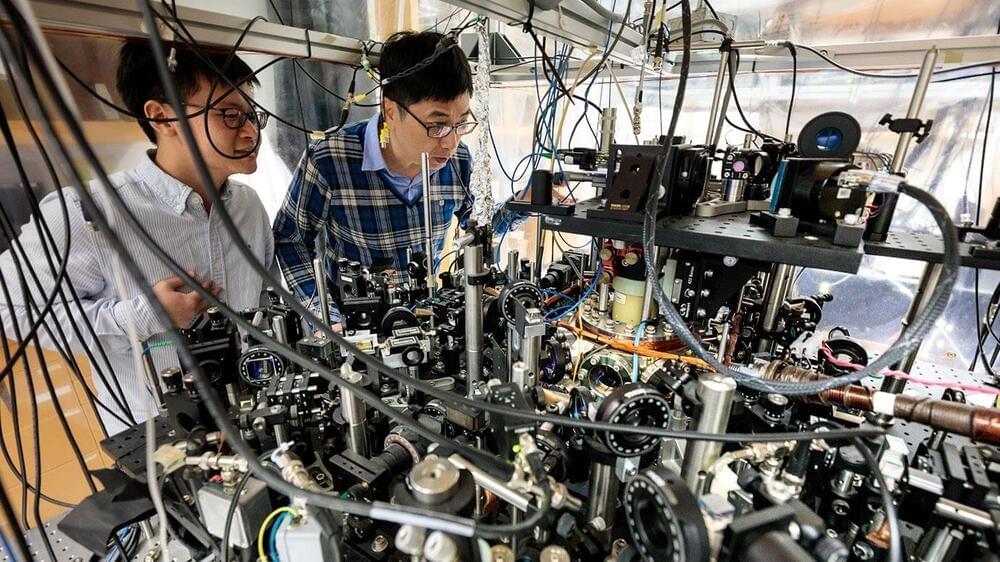

“What we saw lined up with the theoretical predictions,” says Cheng Chin, a physicist at the University of Chicago and senior author of the study. “This has been a scientific goal for 20 years, so it’s a very exciting era.”