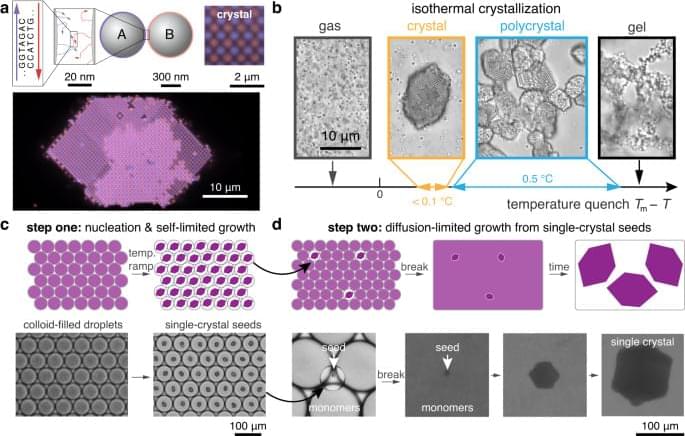

DNA-programmed self-assembly leverages the chemical specificity of DNA hybridization to stabilize user-prescribed crystal structures1,2. Pioneering studies have demonstrated that DNA hybridization can guide the self-assembly of a wide variety of nanoparticle crystal lattices, which can grow to micrometer dimensions and contain millions of particles3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Attention has now turned toward the goal of assembling photonic crystals from optical-scale particles (i.e., roughly 100‑1000 nm in diameter)10,11,12 using DNA-programmed interactions. To this end, progress over the past decade has established that DNA can indeed program the self-assembly of bespoke crystalline structures from micrometer-sized colloidal particles13,14,15,16,17,18,19. However, growing single-domain crystals comprising millions of DNA-functionalized, micrometer-sized colloidal particles remains an unresolved barrier to the development of practical technologies based on DNA-programmed assembly. Prior efforts have yielded either single-domain crystals no more than a few dozen micrometers in size13,14,15,16 or larger polycrystalline materials with heterogeneous domain sizes12,15,17,20. These features—small crystal domains, polycrystallinity, and size dispersity—have therefore precluded the use of DNA-coated colloidal crystals in photonic metamaterial applications.

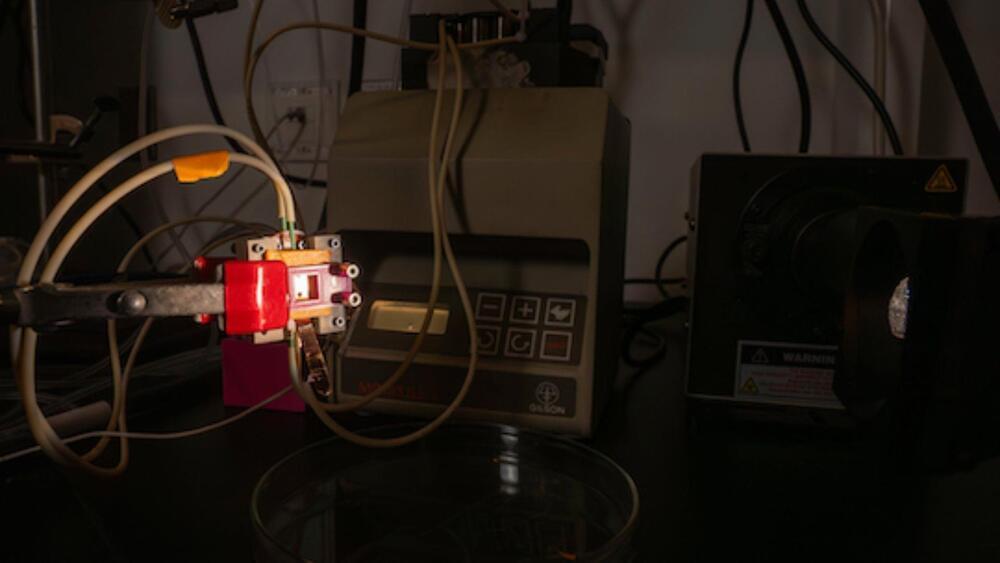

Assembling macroscopic materials from DNA-functionalized, micrometer-sized colloids is challenging due to the vastly different length scales between the DNA molecules and the colloidal particles (Fig. 1a). This combination leads to crystallization kinetics that are extremely sensitive to temperature and prone to kinetic trapping1,21,22,23. The resulting challenges are both practical and fundamental in nature. For example, recent work has shown that crystal nucleation rates can vary by orders of magnitude over a temperature range of only 0.25 °C19. Extremely precise temperature control would therefore be required to self-assemble single-domain crystals from a bulk solution (Fig. 1b). At the same time, annealing polycrystalline materials is difficult due to the combination of the short-range attraction and the friction arising from the DNA-mediated colloidal interactions, which slows the rolling and sliding of colloidal particles at crystalline interfaces15,19,24,25.