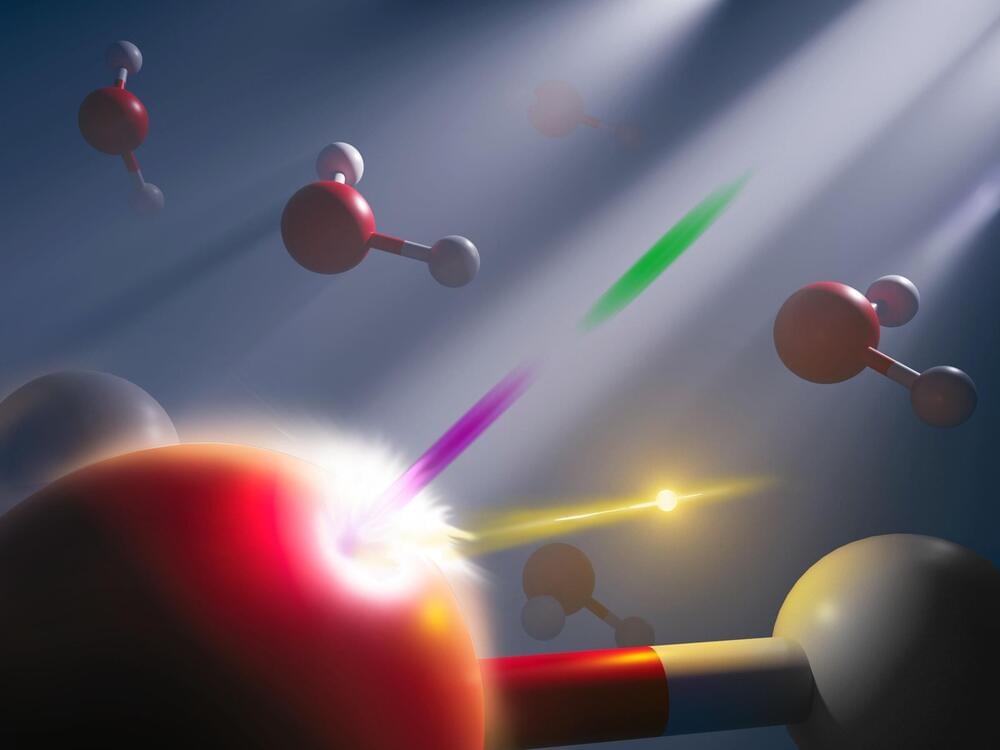

Cells need energy to function. Researchers at the University of Gothenburg can now explain how energy is guided in the cell by small atomic movements to reach its destination in the protein. Imitating these structural changes of the proteins could lead to more efficient solar cells in the future.

The sun’s rays are the basis for all the energy that creates life on Earth. Photosynthesis in plants is a prime example, where solar energy is needed for the plant to grow. Special proteins absorb the sun’s rays, and the energy is transported as electrons inside the protein, in a process called charge transfer. In a new study, researchers show how proteins deform to create efficient transport routes for the charges.

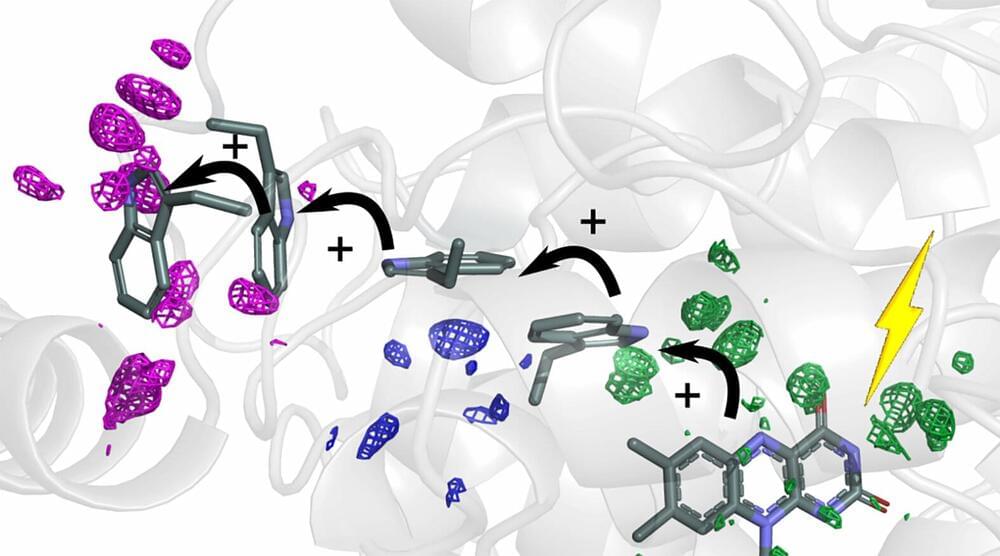

“We studied a protein, photolyase, in the fruit fly, whose function is to repair damaged DNA. The DNA repair is powered by solar energy, which is transported in the form of electrons along a chain of four tryptophans (amino acids). The interesting discovery is that the surrounding protein structure was reshaped in a very specific way to guide the electrons along the chain,” explains Sebastian Westenhoff, Professor of Biophysical Chemistry.