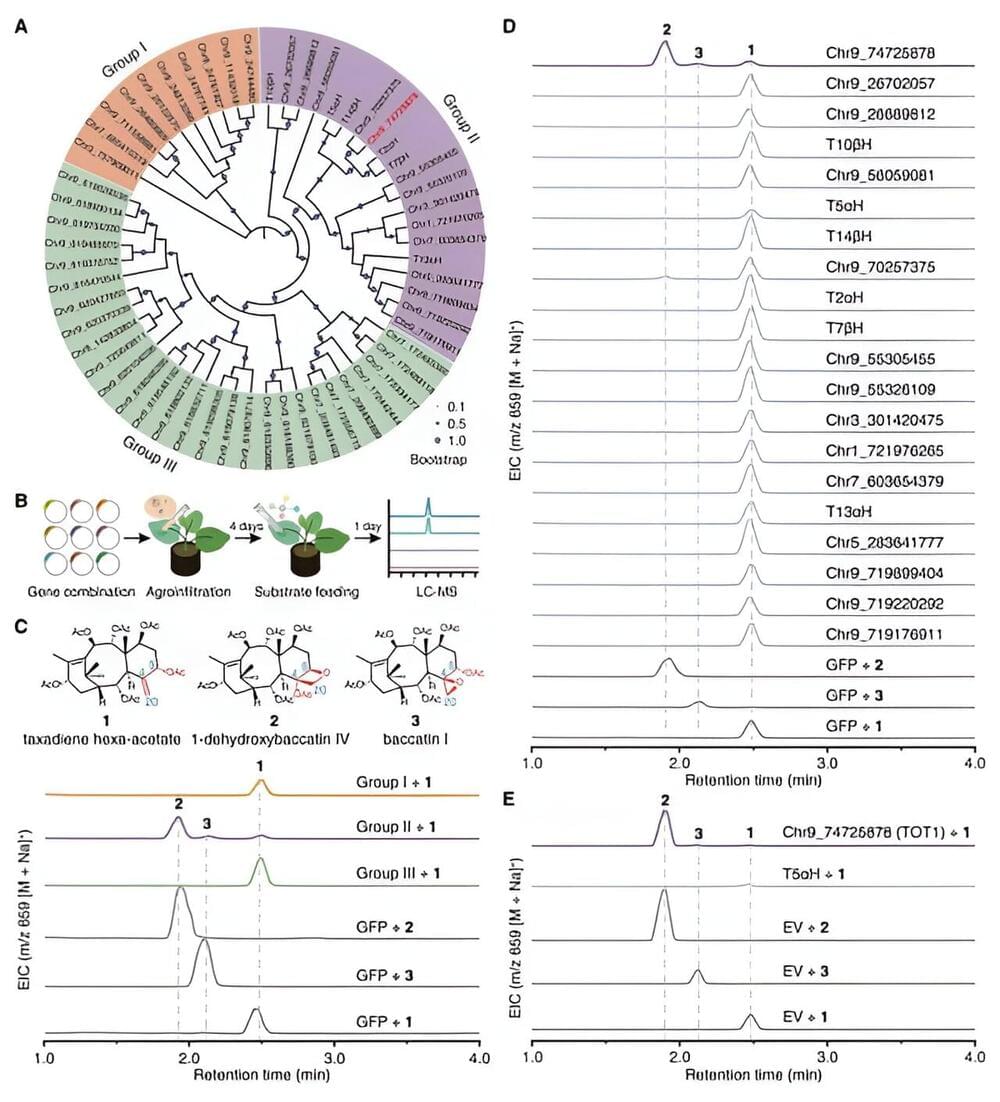

Quantum computers promise to efficiently predict the structure and behaviour of molecules. This Perspective explores how this could overcome existing challenges in computational drug discovery.

Scientists at the National University of Singapore (NUS) have created a microporous covalent organic framework with dense donor–acceptor lattices and engineered linkages for the efficient and clean production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) through the photosynthesis process with water and air.

Traditional industrial production of H2O2 via the anthraquinone process using hydrogen and oxygen, is highly energy-intensive. This approach employs toxic solvents and expensive noble-metal catalysts, and generates substantial waste from side reactions.

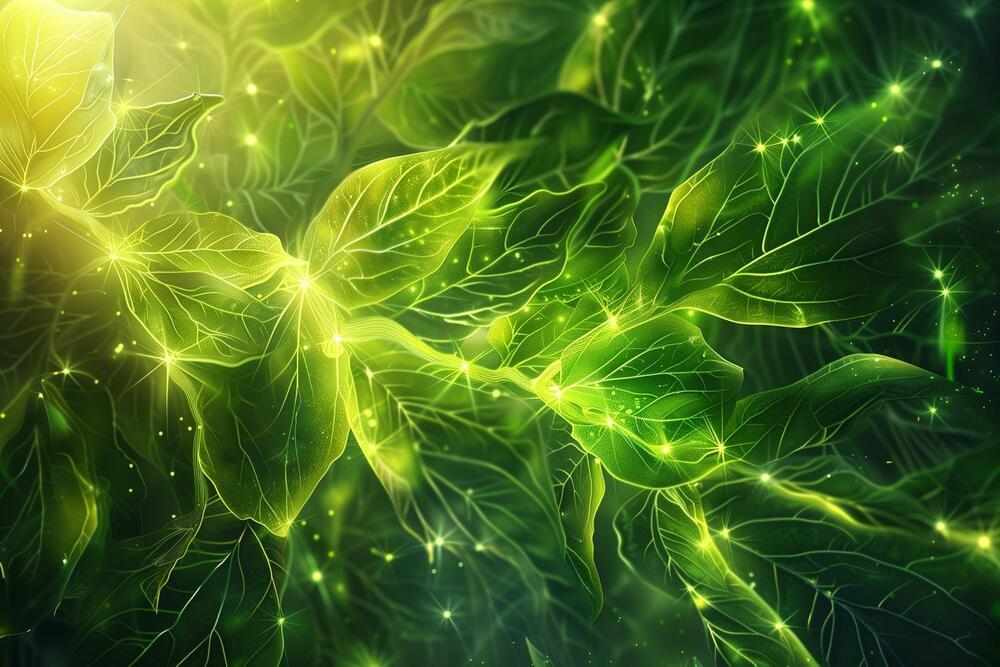

Paclitaxel is the world’s best-selling plant-based anticancer drug and one of the most effective anticancer drugs over the past 30 years. It is widely used in the treatment of various types of cancer, including breast cancer, lung cancer, and ovarian cancer.

In the late 1990s and early 21st century, the annual sales of paclitaxel exceeded $1.5 billion and reached $2.0 billion in 2001, making it the best-selling drug in 2001. In 2019, the market for paclitaxel and its derivatives was approximately $15 billion, and it is expected to reach $20 billion by 2025.

As an anticancer drug, the molecular structure of paclitaxel is extremely complex, with highly oxidized, intricate bridged rings and 11 stereocenters, making it widely recognized as one of the most challenging natural products to synthesize chemically. Since the first total synthesis of paclitaxel was reported by the Holton and Nicolaou research groups in 1994, more than 40 research teams have been engaged in the total synthesis of paclitaxel.

“Enriched cosmic dust, on the other hand, I think makes for a plausible source.”

Dr. Walton’s team now plans to test their theory experimentally, using large reaction vessels to recreate the conditions that might have prevailed in the primeval melt holes, then setting the initial conditions to those that probably existed in a cryoconite hole four billion years ago before waiting to see whether any chemical reactions of the kind that produce biologically relevant molecules do indeed develop.

The post Scientists say cosmic dust may have kick-started life on Earth appeared first on Talker.

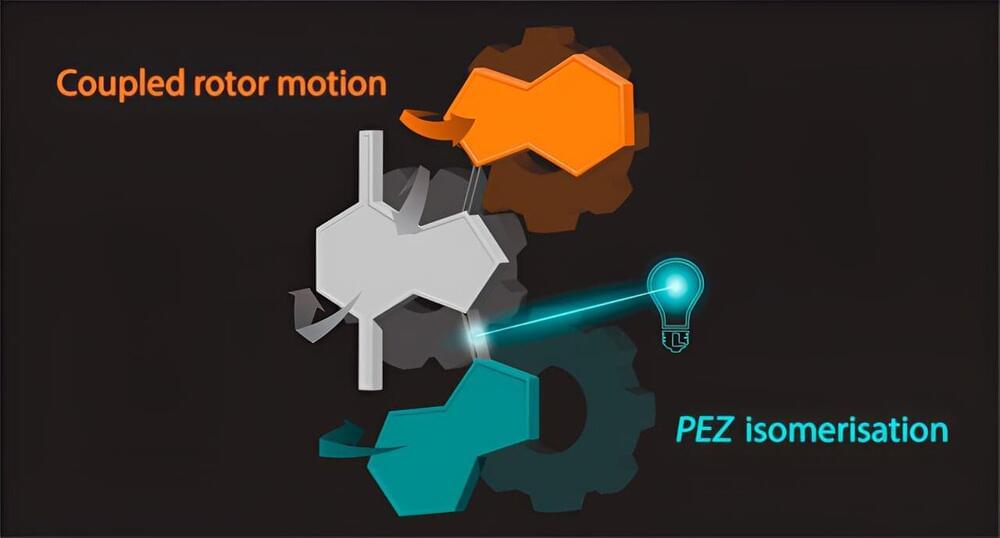

A pair of chemists at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, has observed communication between rotors in a molecular motor. In their study, reported in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, Carlijn van Beek and Ben Feringa conducted experiments with alkene-based molecular motors.

Molecular motors are natural or artificial molecular machines that convert energy into movement in living organisms. One example would be DNA polymerase turning single-stranded DNA into double-stranded DNA. In this new effort, the researchers were experimenting with light-driven, alkene-based molecular motors, using light to drive molecular rotors. As part of their experiments, they created a motor comprising three gears and two rotors and observed an instance of communication between two of the rotors.

To build their motor, the researchers started with parts of existing two motors, bridging them together. The resulting isoindigo structure, they found, added another dimension to their motor relative to other synthesized motors—theirs had a doubled, metastable intermediary connecting two of the rotors, allowing for communication between the two.

The story of how life started on Earth is one that scientists are eager to learn. Researchers may have uncovered an important detail in the plot of chapter one: an explanation of how bubbles of fat came to form the membranes of the very first cells.

A key part of the new findings, made by a team from The Scripps Research Institute in California, is that a chemical process called phosphorylation may have happened earlier than previously thought.

This process adds groups of atoms that include phosphorus to a molecule, bringing extra functions with it – functions that can turn spherical collections of fats called protocells into more advanced versions of themselves, able to be more versatile, stable, and chemically active.

Computing has already accelerated scientific discovery. Now scientists say a combination of advanced AI with next-generation cloud computing is turbocharging the pace of discovery to speeds unimaginable just a few years ago.

Microsoft and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) in Richland, Washington, are collaborating to demonstrate how this acceleration can benefit chemistry and materials science – two scientific fields pivotal to finding energy solutions that the world needs.

Scientists at PNNL are testing a new battery material that was found in a matter of weeks, not years, as part of the collaboration with Microsoft to use to advanced AI and high-performance computing (HPC), a type of cloud-based computing that combines large numbers of computers to solve complex scientific and mathematical tasks.

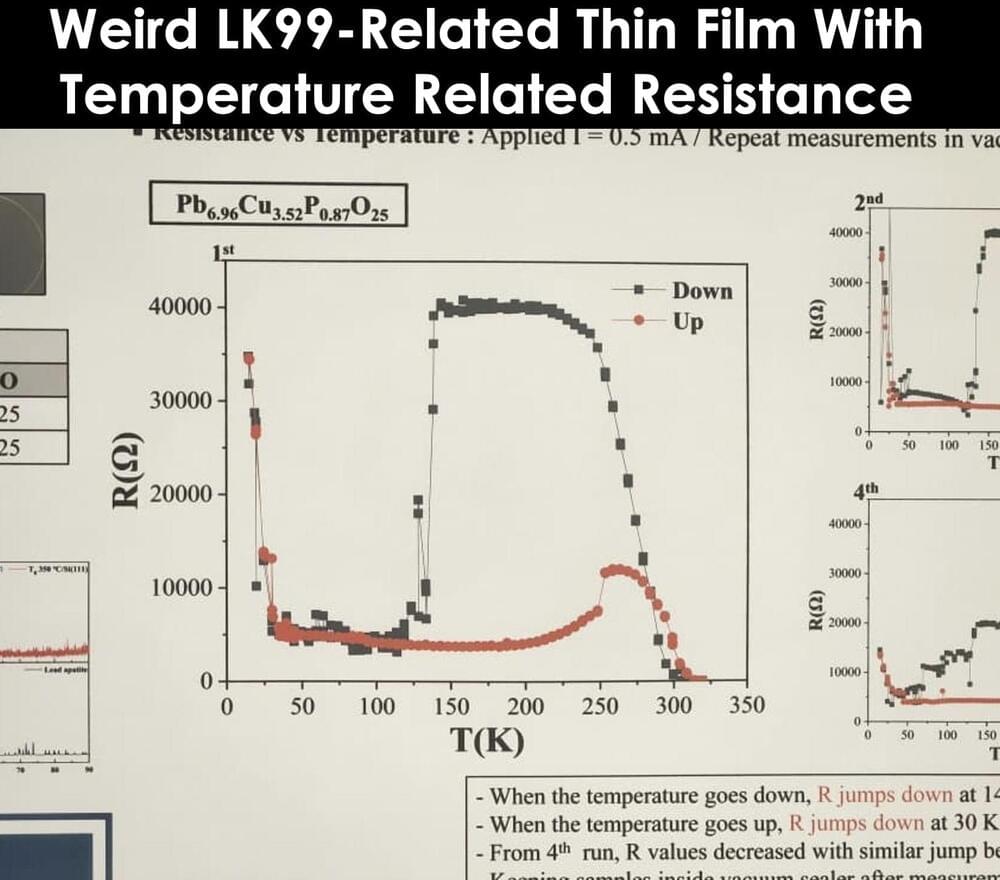

There was a APS presentation by Ulsan Korea University researchers.

It is being reported that numerous comments on the Chinese website Zhihu imply that the University of Ulsan’s data plot is so important that a certain superconductivity expert saw the decisive signal proving LK99’s superconductivity in the graph’s temperature rise curve near 200K.

Nextbigfuture does not understand how a resistance rise implies any superconductivity but it is a thin film LK99-related material. Previously, LK99 thin film analysis by the original Korea researchers had found superconducting levels of resistance with chemically vapor deposited thin film.

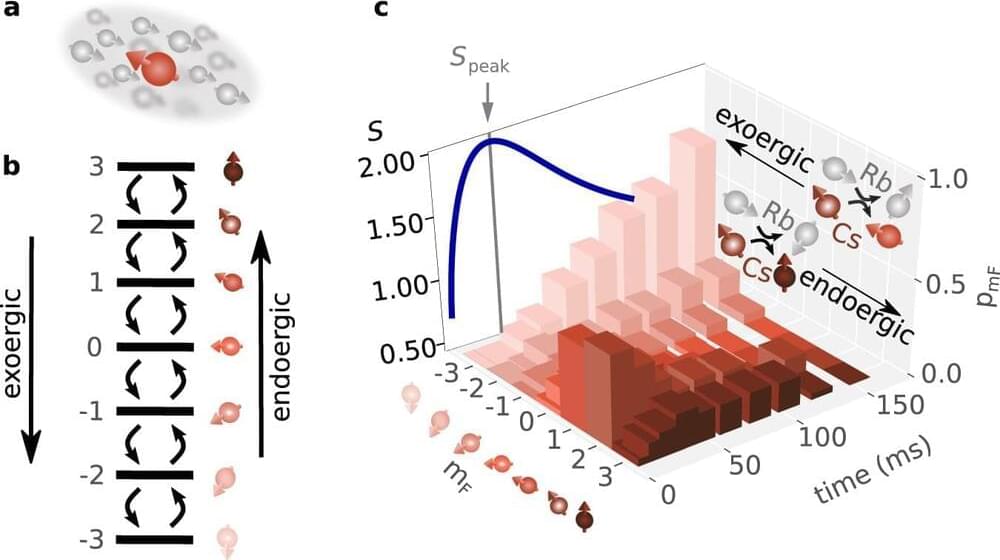

Universal behavior is a central property of phase transitions, which can be seen, for example, in magnets that are no longer magnetic above a certain temperature. A team of researchers from Kaiserslautern, Berlin and Hainan, China, has succeeded for the first time in observing such universal behavior in the temporal development of an open quantum system, a single cesium atom in a bath of rubidium atoms.

This finding helps to understand how quantum systems reach equilibrium. This is of interest to the development of quantum technologies, for example. The study has been published in Nature Communications.

Phase transitions in chemistry and physics are changes in the state of a substance, for example, the change from a liquid to a gaseous phase, when an external parameter such as temperature or pressure is changed.

Catalysts unlock pathways for chemical reactions to unfold at faster and more efficient rates, and the development of new catalytic technologies is a critical part of the green energy transition.

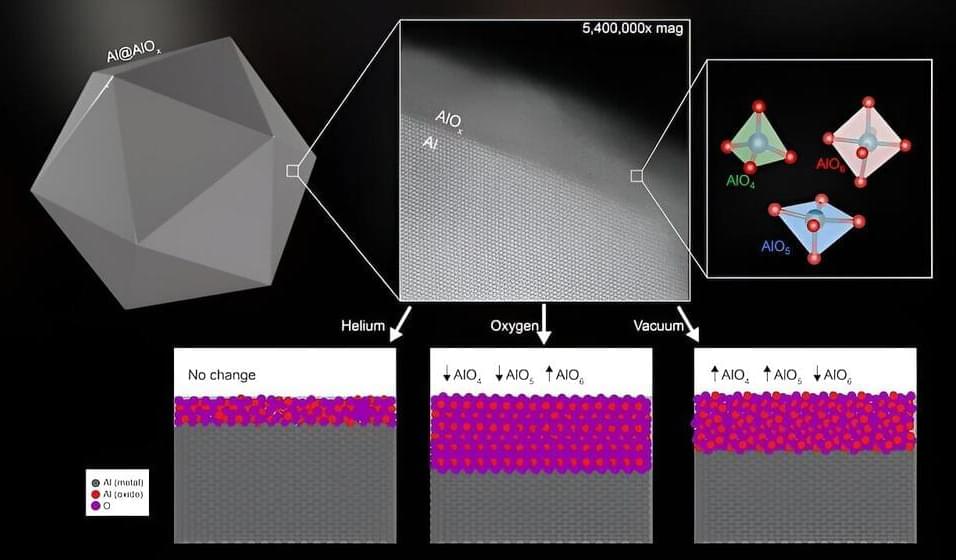

The Rice University lab of nanotechnology pioneer Naomi Halas has uncovered a transformative approach to harnessing the catalytic power of aluminum nanoparticles by annealing them in various gas atmospheres at high temperatures.

According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Rice researchers and collaborators showed that changing the structure of the oxide layer that coats the particles modifies their catalytic properties, making them a versatile tool that can be tailored to suit the needs of different contexts of use from the production of sustainable fuels to water-based reactions.