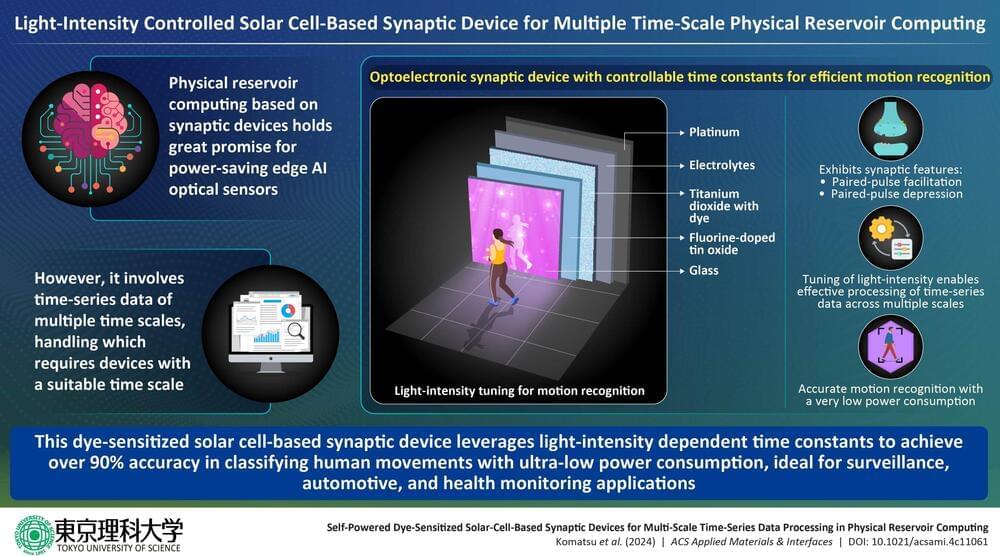

Researchers at Tokyo University of Science have developed a solar cell-based optoelectronic device that mimics human synapses for efficient edge AI processing.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming increasingly useful for the prediction of emergency events such as heart attacks, natural disasters, and pipeline failures. This requires state-of-the-art technologies that can rapidly process data. In this regard, reservoir computing, specially designed for time-series data processing with low power consumption, is a promising option.

It can be implemented in various frameworks, among which physical reservoir computing (PRC) is the most popular. PRC with optoelectronic artificial synapses (junction structures that permit a nerve cell to transmit an electrical or chemical signal to another cell) that mimic human synaptic elements are expected to have unparalleled recognition and real-time processing capabilities akin to the human visual system.

However, PRC based on existing self-powered optoelectronic synaptic devices cannot handle time-series data across multiple timescales, present in signals for monitoring infrastructure, natural environment, and health conditions.