SHA-256 is a one way hashing algorithm. Cracking it would have tectonic implications for consumers, business and all aspects of government including the military.

It’s not the purpose of this post to explain encryption, AES or SHA-256, but here is a brief description of SHA-256. Normally, I place reference links in-line or at the end of a post. But let’s get this out of the way up front:

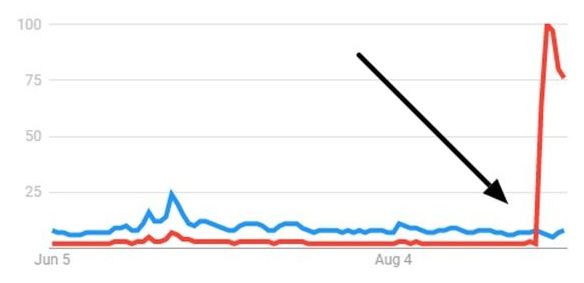

- Sept 11: Original disclosure

- Sept 11: Community skepticism

- Sept 12: Claim retracted: [announcement] [press]

One day after Treadwell Stanton DuPont claimed that a secret project cracked SHA-256 more than one year ago, they back-tracked. Rescinding the original claim, they announced that an equipment flaw caused them to incorrectly conclude that they had algorithmically cracked SHA-256.