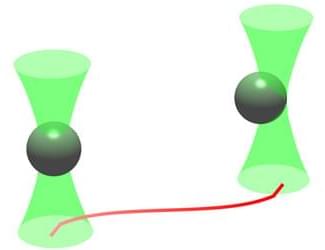

Reid was part of a 60-participant clinical trial that looked to use spinal cord stimulation to regain control of both hands. Similar treatments have shown promise in paraplegic patients, restoring the ability to walk in just a day. But those required surgery to place electrodes on the spinal cord.

ARC-EX therapy, by contrast, delivers two different types of electrical pulses through the skin—no surgery required. Developed by Grégoire Courtine and colleagues at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, the device improved hand strength, pinch, and other movements in 72 percent of participants.

Because the device is non-invasive, it’s a simple addition to physical rehabilitation programs—a sort of pilates for the fingers, explained the team. The trial only included two months of stimulation, and extending the timeline could potentially further improve results.