Marking a major breakthrough in medical development, scientists have used AI to design antibodies from scratch.

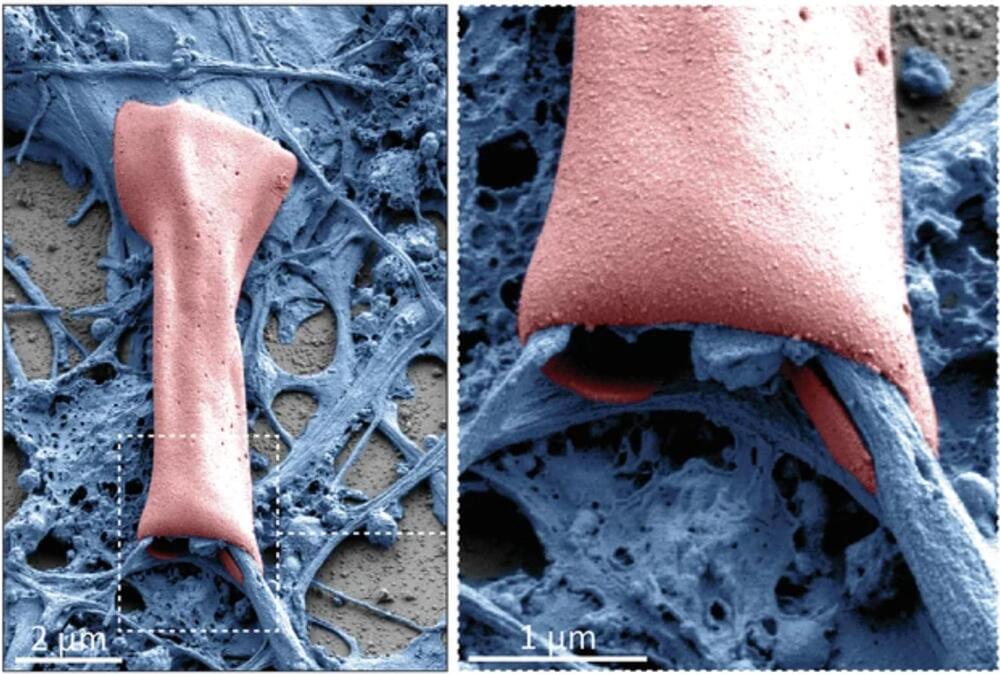

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a well-known gene delivery tool with a wide range of applications, including as a vector for gene therapies. However, the molecular mechanism of its cell entry remains unknown. Here, we performed coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations of the AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) capsid and the universal AAV receptor (AAVR) in a model plasma membrane environment. Our simulations show that binding of the AAV2 capsid to the membrane induces membrane curvature, along with the recruitment and clustering of GM3 lipids around the AAV2 capsid. We also found that the AAVR binds to the AAV2 capsid at the VR-I loops using its PKD2 and PKD3 domains, whose binding poses differs from previous structural studies. These first molecular-level insights into AAV2 membrane interactions suggest a complex process during the initial phase of AAV2 capsid internalization.

The small-scale FDA-cleared trial is designed to evaluate both the safety and initial efficacy of RB-ADSCs in nine patients with Alzheimer’s. Regeneration Biomedical’s CTAD presentation focused on the first three enrolled patients, who each received a single dose of RB-ADSCs delivered directly into the lateral ventricles of the brain using an “Ommaya reservoir” – a device implanted under the scalp to bypass the blood-brain barrier, a major obstacle in Alzheimer’s treatments.

Biomarker analysis at the 12-week mark demonstrated reductions in both p-Tau and amyloid-beta – two proteins strongly associated with Alzheimer’s disease progression. In cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from the three patients, p-Tau levels decreased to “normal” levels, while amyloid PET scans also showed a reduction in amyloid buildup.

Regeneration Biomedical also reported its treatment produced signs of cognitive improvement, with two of the three patients showing increased Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, a common measure of cognitive function.

In a groundbreaking Nature paper, researchers have developed synthetic regulatory sequences that could prevent targeted gene therapies from having effects in unwanted cell types.

More than methylation

While methylation is the most well-known regulator of gene expression, it isn’t the only thing that determines what is to be expressed when. Cis-regulatory elements (CREs), so called because they sit near the DNA sequences they regulate, are responsible for expressing the genes that are specific to each cell type [1]. While they are technically non-coding, as they do not directly code for functional proteins, CREs are critical to epigenomic function.

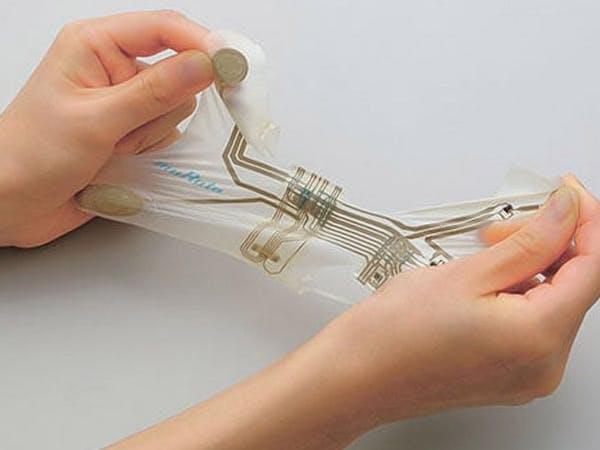

Murata is branching out from its usual ceramic components with the launch of flexible, stretchable electronics — a Stretchable Printed Circuit (SPC) platform it says is ideally positioned for wearable and medical devices.

In recent years, in the medical field, to make more accurate diagnoses, the…

Bendy, soft, stretchy devices target the wearable and medical markets.

Dr. Abba Zubair, MD: “Our hope is to study these space-grown cells to improve treatment for age-related conditions such as stroke, dementia, neurodegenerative diseases and cancer.”

What can microgravity teach us about stem cell growth? This is what a recent study published in NPJ Microgravity hopes to address as a pair of researchers from the Mayo Clinic investigated past research regarding the growth properties of stem cells, specifically regeneration, differentiation, and cell proliferation in microgravity and whether the stem cells can maintain these properties after returning to Earth. This study holds the potential to help researchers better understand how stem cell growth in microgravity can be transitioned into medical applications, including tissue growth for disease modeling.

“The goal of almost all space flight in which stem cells are studied is to enhance growth of large amounts of safe and high-quality clinical-grade stem cells with minimal cell differentiation,” said Dr. Abba Zubair, MD, who is a faculty at the Mayo Clinic and the sole co-author on the study. “Our hope is to study these space-grown cells to improve treatment for age-related conditions such as stroke, dementia, neurodegenerative diseases and cancer.”

For the study, the researchers examined past research that launched stem cell cultures to the International Space Station (ISS) to have astronauts onboard evaluate the stem cells’ growth patterns and behavior under microgravity conditions. Dr. Zunair has launched stem cells to the ISS on three occasions and the various types of stem cells examined on the ISS in previous research include mesenchymal stem cells, hematopoietic stem cells, cardiovascular progenitor stem cells, and neural stem cells.

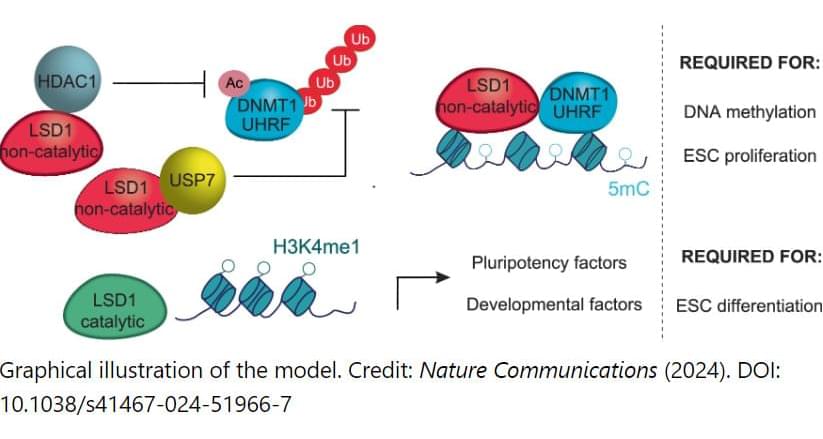

A study led by Umeå University, Sweden, presents new insights into how stem cells develop and transition into specialized cells. The discovery can provide increased understanding of how cells divide and grow uncontrollably so that cancer develops.

“The discovery opens a new track for future research into developing new and more effective treatments for certain cancers,” says Francesca Aguilo, associate professor at the Department of Molecular Biology at Umeå University and leader of the study in collaboration with various institutions including the University of Pavia, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Universidad de Extremadura, and others.

All cells in the body arise from a single fertilized egg. From this single origin, various specialized cells with widely differing tasks evolve through a process called cellular differentiation. Although all cells share the same origin and share the same genetic information, specialized cells use the information in different ways to perform different functions. This process is regulated by genetic and epigenetic mechanisms.

In a world where choices seem endless, could it be that our ‘free will’ is nothing more than an illusion?

When it comes to things like choosing a morning run over an extra hour of sleep, opting for an apple instead of that enticing pint of ice cream, or quitting your job on a whim…

…What’s truly guiding these decisions? Is it willpower, biology, environment, or perhaps a unique strength of character we’ve built over time?

Or… could it be something else entirely, something beyond our control?

Here’s where our guest, Dr. Robert Sapolsky — a renowned Professor of Biology, Neurology and Neurosurgery at Stanford University — offers us a slightly unsettling, yet eye-opening, perspective.

He suggests that every decision we make — from the podcasts we tune into, to judges making a case verdict, to choosing our life partner — isn’t shaped by any sort of conscious control or free will. Instead, he believes our actions are driven by factors beyond our grasp and influence.