Further, “the necessity to secure private ideas, plans, and brain data from unpermitted viewing is accorded to Dr. Anita S Jwa by the phrase,” she argues. Besides that, the ethical implications in the fields of informed consent, coercion, and fairness with respect to the common attributes of the BCIs must be critically considered. For example, consider a scenario where a BCI is used to control a prosthetic limb. Without proper privacy measures, “unauthorised access to the BCI could lead to manipulation of the prosthetic limb,” posing risks to the user’s safety and autonomy.

Overcoming these difficulties requires the joint efforts of all the stakeholders, such as researchers, policymakers, and industry leaders. In the same way, we have to critically assess the technical, ethical, and accessibility issues in BCI. We may then be able to capture the potential of these BCIs and ultimately improve human lives.

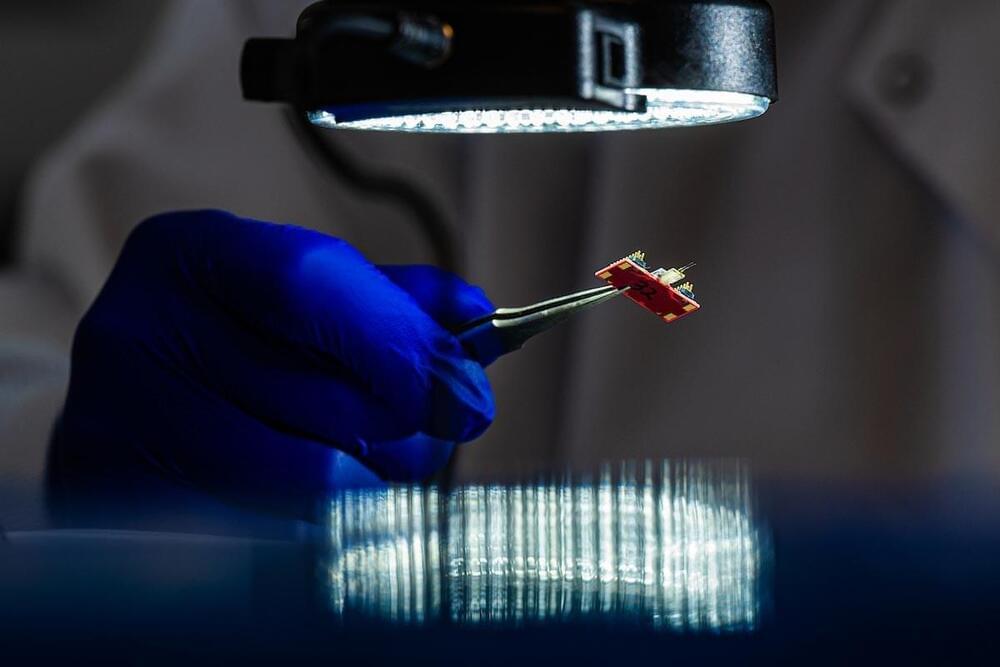

In this instance, just imagine that we are submerging into the future of BCIs, and to my surprise, it feels like living in a movie where sci-fi is a reality! BCIs are going to be able to do all kinds of really advanced things very soon. People are going to think that they are very cool. We are entering an entirely new realm of brainy gadgets that are becoming smaller, sleeker, and oh-so-wearable. It is now all gear change; the future of BCI is almost as organic as slipping on your dream pair of sunglasses.