1. Introduction.

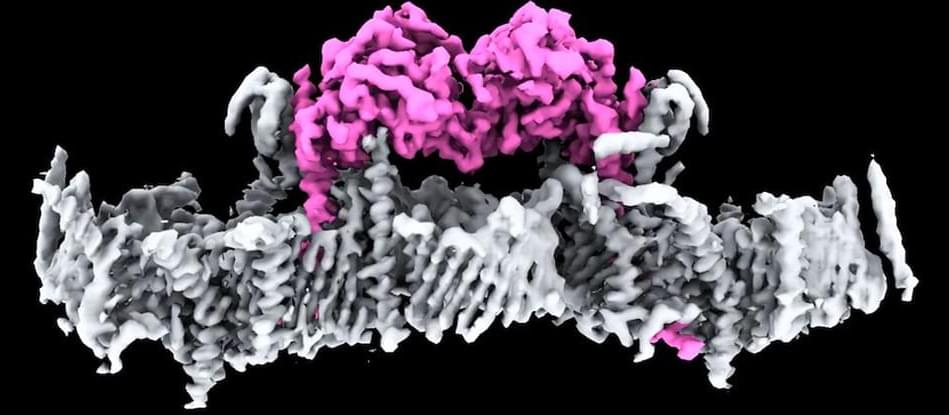

The natural production of EGF, a short polypeptide hormone, promotes the processes of proliferation, expansion, and division of cells [1]. For in vitro cell culture, EGF functions as a growth factor [2] and has an effective mitogenic effect on endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and most epithelial tissues. Its biological functions rely on associating itself with a specific cell membrane receptor [3]. Because EGF plays a crucial role as a mitogen in the proliferation of various cell types both in vivo and in vitro, it has been used in the therapeutic and cosmetic areas [4] to cover scars and reduce the appearance of aging skin [1]. Moreover, recombinant EGF is used topically for diabetic foot ulcers [5]. The structures and properties of proteins vary; favorable conditions are necessary for conformation, stability, and proper function. In contrast, a protein degrades, denatures, or precipitates when it is exposed to unfavorable conditions or when its natural environment changes suddenly. Recombinant human EGF is most frequently degraded by oxidation and deamidation [6]. These reactions typically have long-term implications. For protein solutions to remain stable and have a longer shelf life, excipients may need to be added, depending on how the protein is used in the experiment and other factors. When it comes to the chemical and physical degradation of proteins, the solution environment plays a crucial role in protein formulations. Of particular concern are buffer types, pH, and antioxidants [7]. Even though antioxidants assist in stability and solubility in liquid solutions, which help to preserve protein structure and function, they are frequently considered inactive ingredients in pharmaceutical compositions [8] [9].

Since an unstable protein solution can impact the product’s appearance, potency, purity, healing effects, and cell proliferation, in vitro protein stabilization is an essential practical consideration for the development of an effective EGF formulation. The stability of EGF in solution has been well documented in several in vivo solutions [10]. Though there have been numerous reports on EGF stability, none have specifically addressed treatment in cell culture conditions. Since it has a big influence on several aspects of the parenteral formulation creation process and EGF-based cell proliferation, the study of EGF stability in cell culture medium has gotten little attention. But since many of these in vitro tests are conducted in non-physiological settings, such as organic solvents or acidic solutions [11], they frequently fail to yield qualitatively positive results in cellular therapies.