Scientists at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have uncovered a surprising way in which harmful bacteria prepare to attack their hosts. The discovery, led by Ph.D. students Lior Aroeti, Netanel Elbaz under the guidance of Prof. Ilan Rosenshine from the Faculty of Medicine could one day help researchers find new ways to fight infectious diseases.

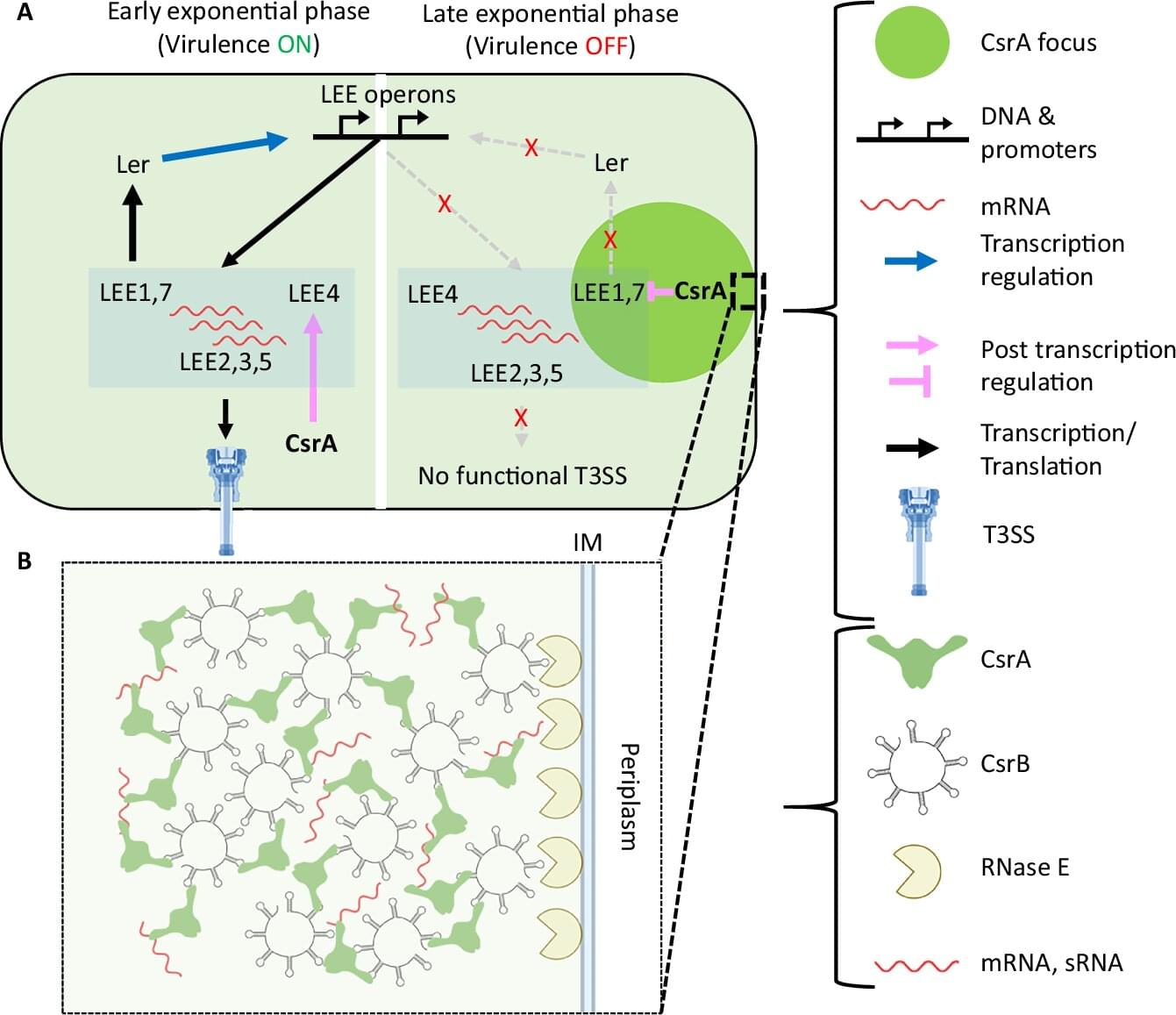

At the heart of this study, now published in Nature Communications, is a protein called CsrA, which acts like a switchboard operator inside bacterial cells. It helps bacteria decide which of their genes to turn on or off—especially the genes that make them dangerous to humans.

Researchers have long known that CsrA plays a central role in bacterial virulence—the ability of bacteria to cause disease. But the new study shows that CsrA doesn’t work alone. Instead, it gathers in a special, droplet-like structure inside the cell. This structure has no membrane, making it a “membraneless compartment,” which scientists now believe is crucial in regulating how bacteria behave.