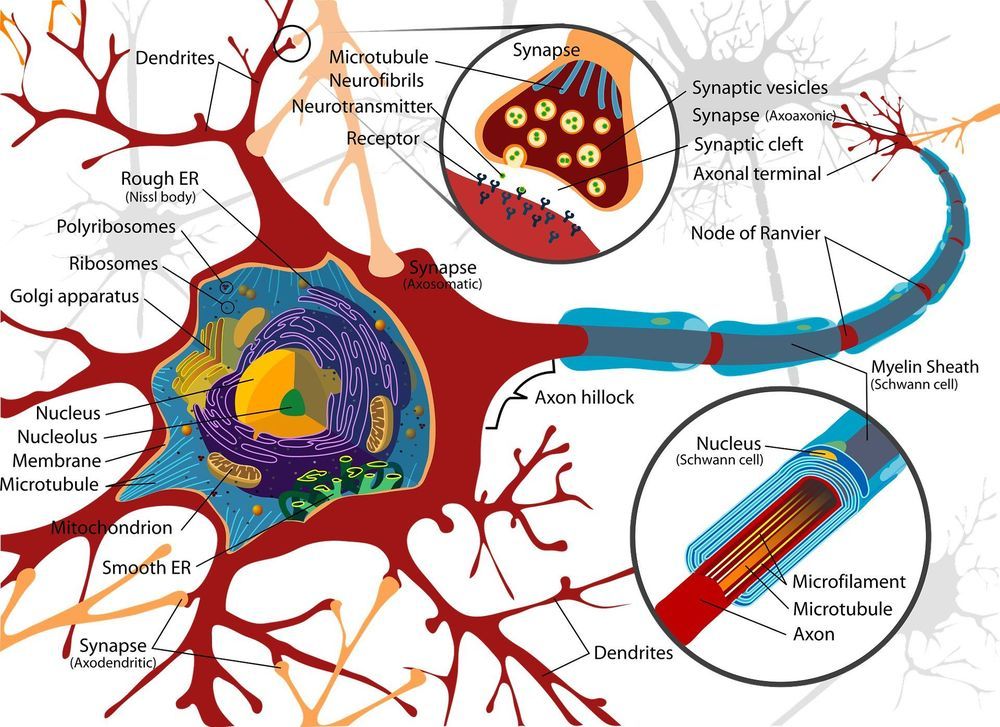

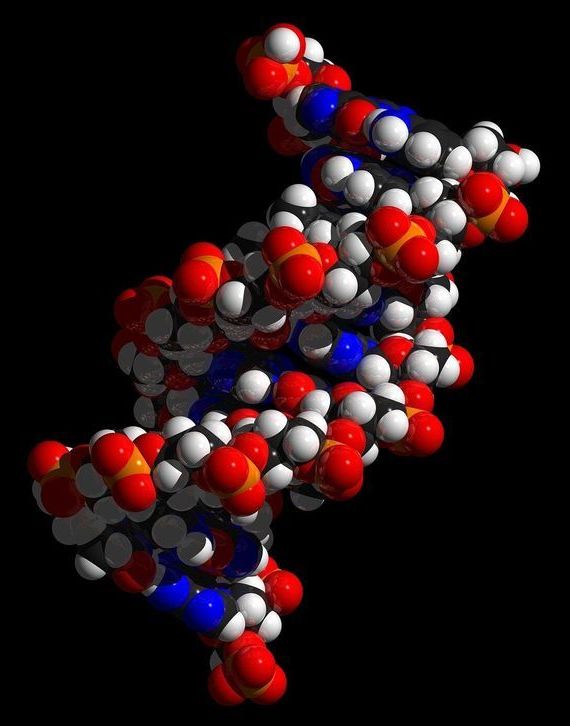

Synthetic biology researchers at Northwestern University have developed a system that can rapidly create cell-free ribosomes in a test tube, then select the ribosome that can perform a certain function.

The system, called ribosome synthesis and evolution (RISE), is an important step toward using ribosomes beyond their natural capabilities. The key feature of RISE is the ability to evolve ribosomes without cell viability constraints. The result could be new ways to synthesize materials, like nylon, or therapies, like new antibiotics that could address rising antibiotic resistance.

“Ribosomes have an extraordinary capability as the protein synthesis machinery of the cell,” said Michael Jewett, Walter P. Murphy Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering and director of the Center for Synthetic Biology at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering, who led the research. “But to synthesize proteins beyond those found in nature, we have to design and modify the ribosome to work with non-natural substrates. Developing ribosomes in vitro is an important part of that system, and we are very excited to have this new capability.”