“The reason a glucose-responsive insulin is important is that the biggest barrier to the effective use of insulin, especially in Type 1 diabetes, is the fear of the consequences of blood sugar going too low,” says study author Michael A. Weiss.

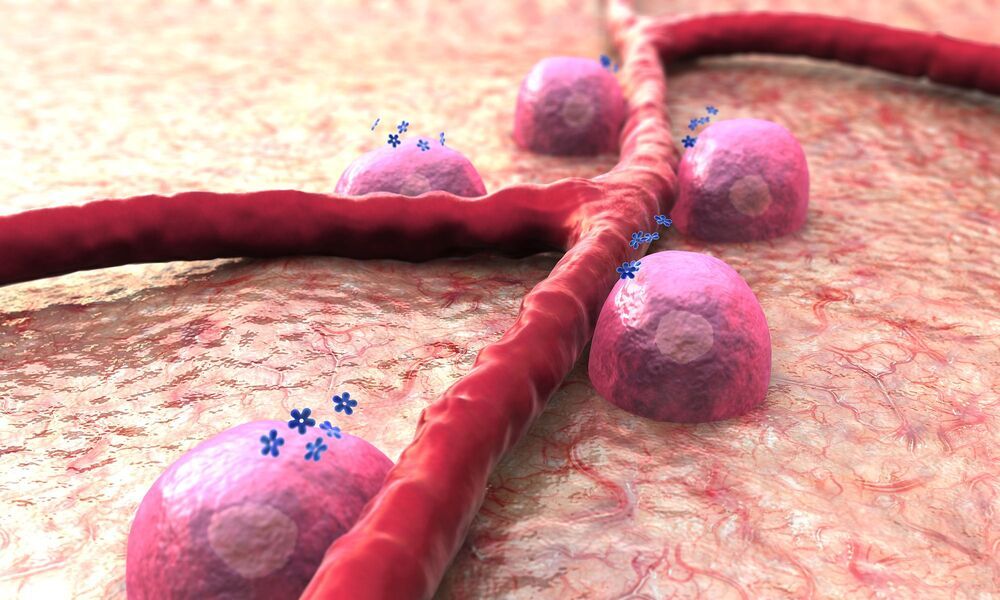

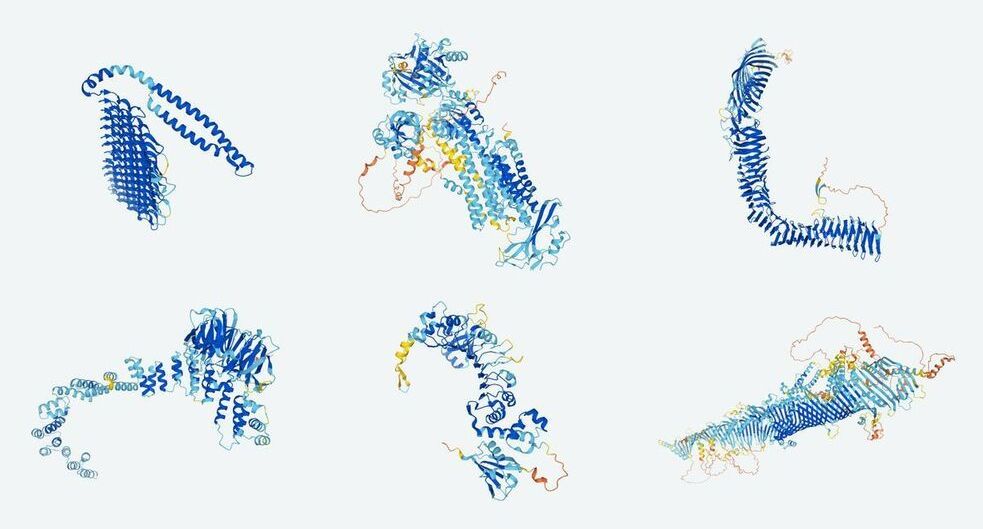

For sufferers of diabetes, keeping blood glucose levels within a healthy range can be a difficult and labor-intensive balancing act that often requires regular insulin injections, but some scientists imagine a future where medicine does the heavy lifting for them. A team at Indiana University School of Medicine has taken a promising step towards this future, demonstrating a type of “synthetic hinge” that swings into action when blood glucose levels call for corrective action.

The hormone insulin plays a vital role in keeping glucose at healthy levels in the blood, pulling it out of the bloodstream and helping turn it into energy. In diabetes patients, insufficient amounts or insulin that results in a reduction in effectiveness means that blood glucose levels are left to rise to potentially dangerous levels, which can have serious consequences.

Injections of insulin are a way for Type 1 diabetics to manage the condition, but one dangerous side effect of this is the potential for them to drive blood-sugar levels too low, a condition known as hypoglycemia. These concerns have moved scientists to explore a concept known as “glucose-responsive insulin,” an engineered form of the hormone that would self-adjust depending on the blood sugar levels of the patient.