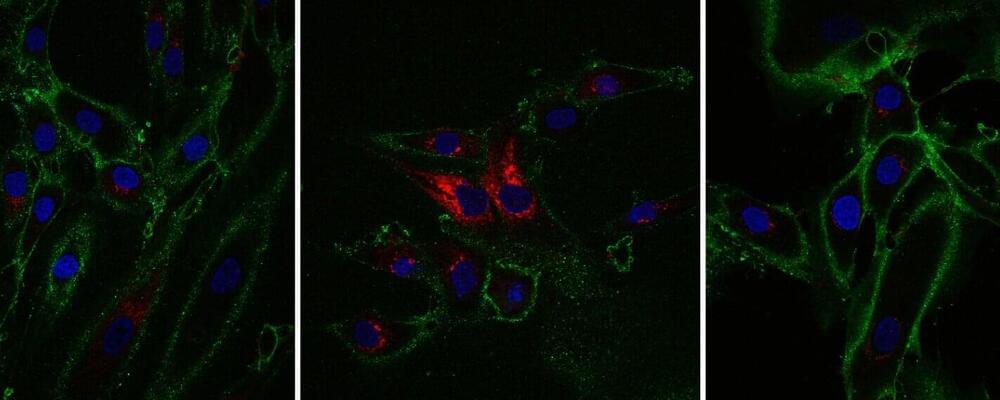

Research from the Babraham Institute has developed a method to “time jump” human skin cells by 30 years, turning back the aging clock for cells without losing their specialized function. Work by researchers in the Institute’s Epigenetics research program has been able to partly restore the function of older cells, as well as rejuvenating the molecular measures of biological age. The research is published today in the journal eLife, and while this topic is still at an early stage of exploration, it could revolutionize regenerative medicine.

What is regenerative medicine?

As we age, our cells’ ability to function declines and the genome accumulates marks of aging. Regenerative biology aims to repair or replace cells including old ones. One of the most important tools in regenerative biology is our ability to create “induced” stem cells. The process is a result of several steps, each erasing some of the marks that make cells specialized. In theory, these stem cells have the potential to become any cell type, but scientists aren’t yet able to reliably recreate the conditions to re-differentiate stem cells into all cell types.