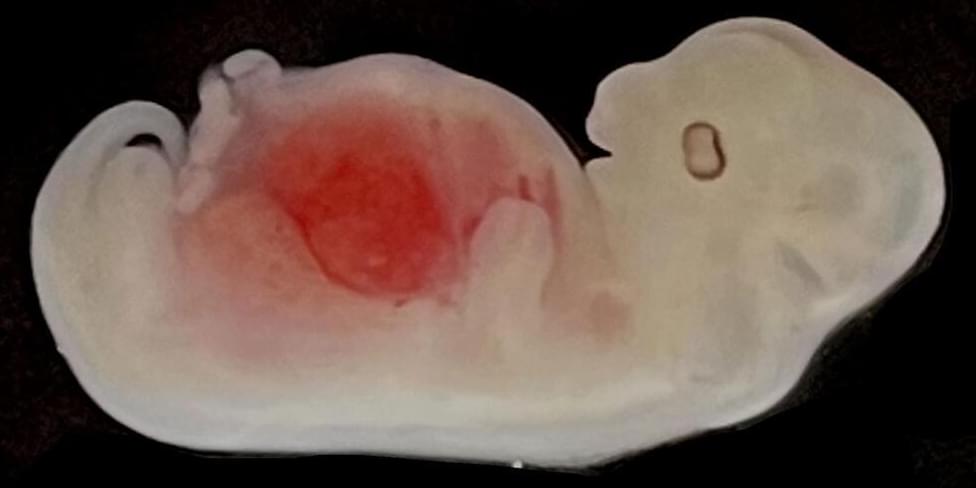

We don’t treat Isla’s vision loss as a sad circumstance or as something that is broken in her. It’s so important for us that she knows her vision impairment is not something that makes her less than. If anything, it makes her a stronger, more amazing person, and we couldn’t be prouder of who she is.

Vision impairment is the only symptom she displays of this disease, and we are fighting with everything we have to ensure it stays this way. We were told on diagnosis day that that day was the healthiest Isla would ever be, and that she was at her peak; two years later, and she has continued to defy that, Stockdale added.

The family believes that Isla’s incredible development is a result of the medication, called Miglustat, which she has been taking since November 2022.