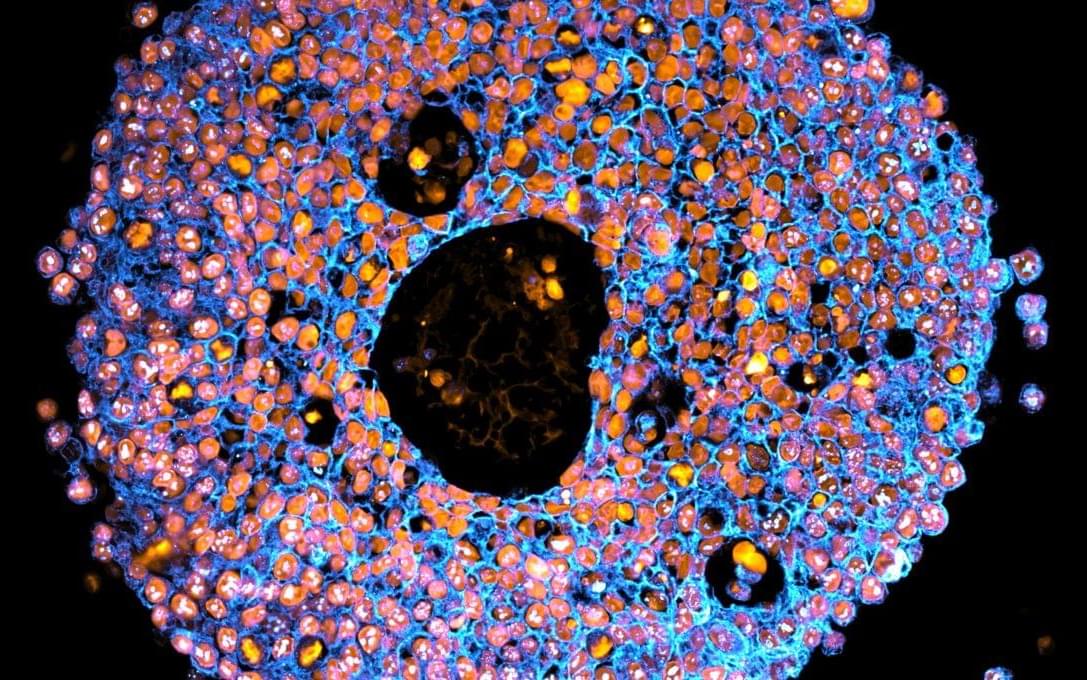

The human kidney filters about a cup of blood every minute, removing waste, excess fluid, and toxins from it, while also regulating blood pressure, balancing important electrolytes, activating Vitamin D, and helping the body produce red blood cells. This broad range of functions is achieved in part via the kidney’s complex organization. In its outer region, more than a million microscopic units, known as nephrons, filter blood, reabsorb necessary nutrients, and secrete waste in the form of urine.

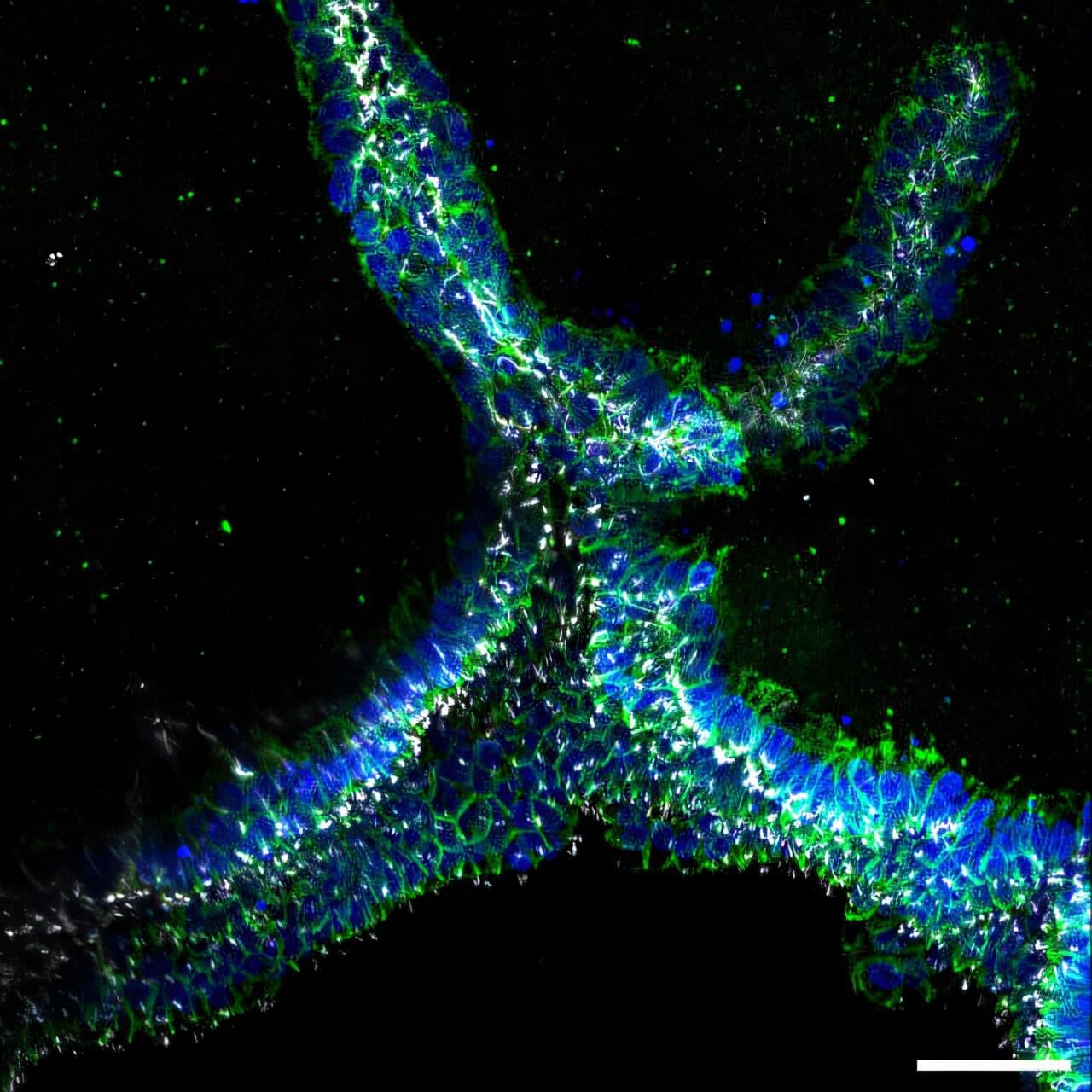

To direct urine produced by this enormous number of blood-filtering units to a single ureter, the kidney establishes a highly branched three-dimensional, tree-like system of “collecting ducts” during its development. In addition to directing urine flow to the ureter and ultimately out of the kidney, collecting ducts reabsorb water that the body needs to retain, and maintain, the body’s balance of salts and acidity at healthy levels.

Finding ways to recreate this system of collecting ducts is the focus of researchers and bioengineers who are interested in understanding how duct defects cause certain kidney diseases, underdeveloped kidneys, or even the complete absence of a kidney. Being able to fabricate the kidney’s plumbing system from the bottom up would be a giant step toward tissue replacement therapies for many patients waiting for a kidney donation: In the U.S. alone, 90,000 patients are on the kidney transplant waiting list. However, rebuilding this highly branched fluid-transporting ductal system is a formidable challenge and not possible yet.