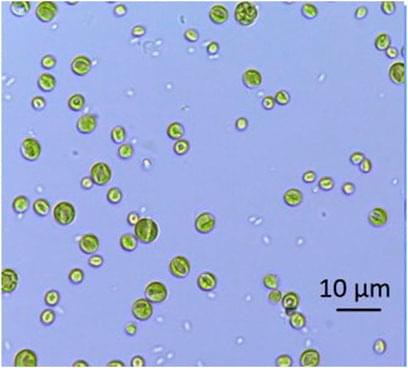

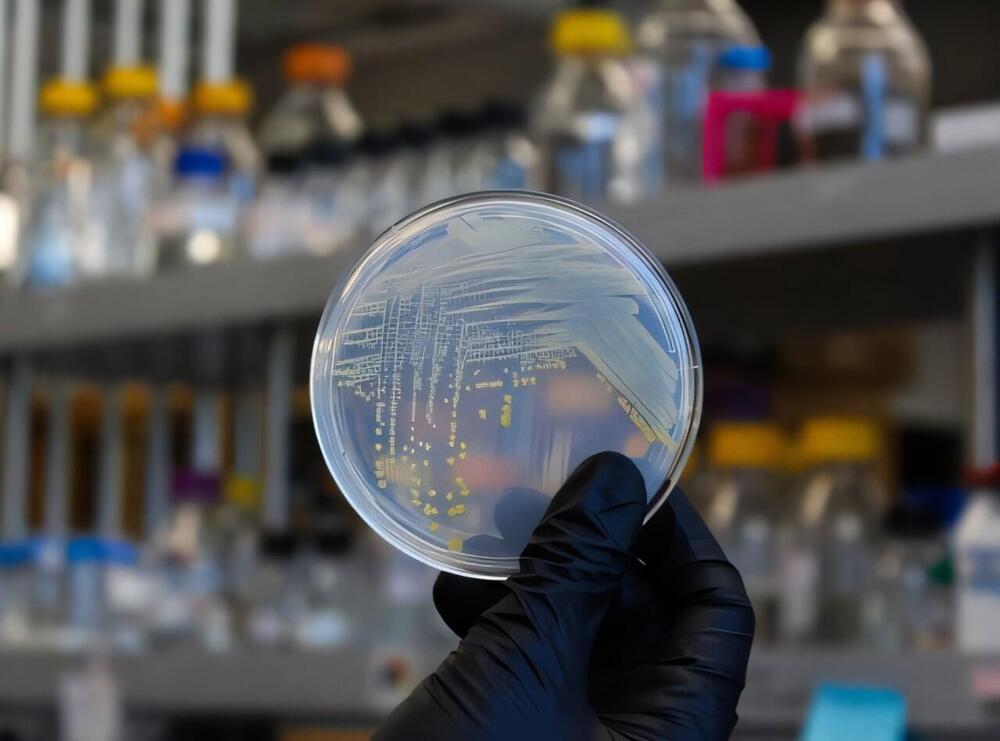

These scenarios pose several new challenges, since the environmental and operational conditions of the mission will strongly differ than those on the International Space Station (ISS). One critical parameter will be the increased mission duration and further distance from Earth, requiring a Life Support System (LSS) as independent as possible from Earth’s resources. Current LSS physico-chemical technologies at the ISS can recycle 90% of water and regain 42% of O2 from the astronaut’s exhaled CO2, but they are not able to produce food, which can currently only be achieved using biology. A future LSS will most likely include some of these technologies currently in use, but will also need to include biological components. A potential biological candidate are microalgae, which compared to higher plants, offer a higher harvest index, higher biomass productivity and require less water. Several algal species have already been investigated for space applications in the last decades, being Chlorella vulgaris a promising and widely researched species. C. vulgaris is a spherical single cell organism, with a mean diameter of 6 µm. It can grow in a wide range of pH and temperature levels and CO2 concentrations and it shows a high resistance to cross contamination and to mechanical shear stress, making it an ideal organism for long-term LSS. In order to continuously and efficiently produce the oxygen and food required for the LSS, the microalgae need to grow in a well-controlled and stable environment. Therefore, besides the biological aspects, the design of the cultivation system, the Photobioreactor (PBR), is also crucial. Even if research both on C. vulgaris and in general about PBRs has been carried out for decades, several challenges both in the biological and technological aspects need to be solved, before a PBR can be used as part of the LSS in a Moon base. Those include: radiation effects on algae, operation under partial gravity, selection of the required hardware for cultivation and food processing, system automation and long-term performance and stability.

The International Space Station (ISS) has been continuously inhabited for over twenty years. The Life Support System (LSS) on board the station is in charge of providing the astronauts with oxygen, water and food. For that, Physico-Chemical (PC) technologies are used, recycling 90% of the water and recovering 42% of the oxygen (O2) from the carbon dioxide (CO2) that astronauts produce (Crusan and Gatens, 2017), while food is supplied from Earth.

Space agencies currently plan missions beyond Low Earth Orbit, with a Moon base or a mission to Mars as potential future scenarios (ESA Blog 2016; ISEGC 2018; NASA 2020). The higher distance from Earth of a lunar base, compared to the ISS, might require the production of food in-situ, to reduce the amount of resources required from Earth. PC technologies are not able to produce food, which can only be achieved using biological organisms. Several candidates are currently being investigated, with a main focus on higher plants (Kittang et al., 2014; Hamilton et al., 2020) and microalgae (Detrell et al., 2020b; Poughon et al., 2020).