There’s No Turning Back

Not long ago, solving the crystal structure of a protein required an entire PhD.

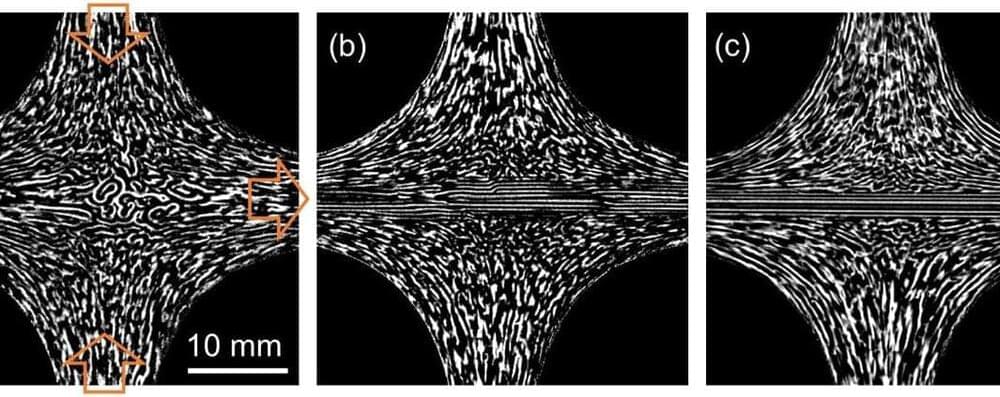

Growing crystals, collecting X-ray diffraction data, and interpreting electron density maps often took years of optimization and expensive instruments. Even then, solving all protein structures was a challenge, further compounding the “protein folding problem” in biology.