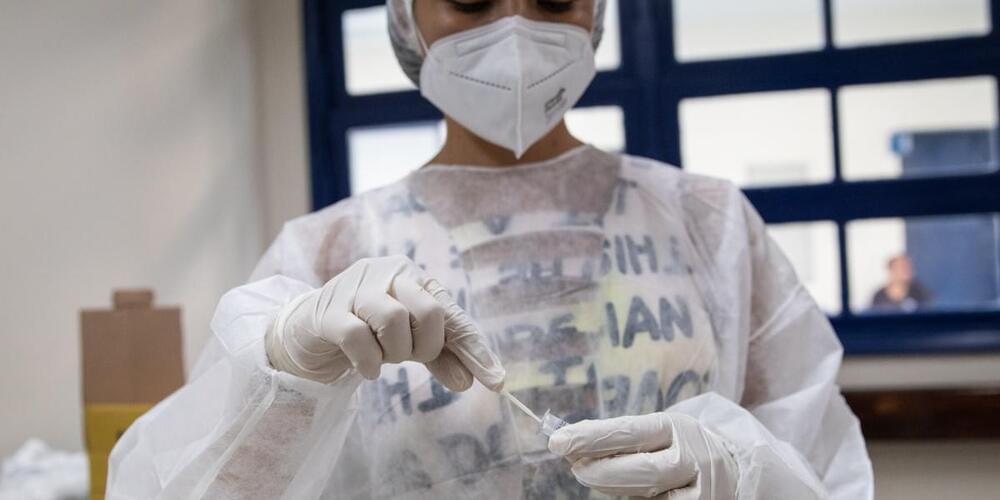

On 30 January 2020 COVID-19 was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) with an official death toll of 171. By 31 December 2020, this figure stood at 1 813 188. Yet preliminary estimates suggest the total number of global deaths attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 is at least 3 million, representing 1.2 million more deaths than officially reported.

With the latest COVID-19 deaths reported to WHO now exceeding 3.3 million, based on the excess mortality estimates produced for 2020, we are likely facing a significant undercount of total deaths directly and indirectly attributed to COVID-19.

COVID-19 deaths are a key indicator to track the evolution of the pandemic. However, many countries still lack functioning civil registration and vital statistics systems with the capacity to provide accurate, complete and timely data on births, deaths and causes of death. A recent assessment of health information systems capacity in 133 countries found that the percentage of registered deaths ranged from 98% in the European region to only 10% in the African region.