Micrometeorites, tiny space rocks, may have helped deliver nitrogen, a vital life ingredient, to Earth during our solar system’s early days. This finding was published in Nature Astronomy on November 30 by an international research team, including scientists from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and Kyoto University. They discovered that nitrogen compounds like ammonium salts are common in material from regions distant from the sun. However, how these compounds reached Earth’s orbit was unclear.

The study suggests that more nitrogen compounds were transported near Earth than previously thought. These compounds could have contributed to life on our planet. The research was based on material collected from the asteroid Ryugu by Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft in 2020. Ryugu, a small sun-orbiting rocky object, is carbon-rich and has experienced considerable space weathering due to micrometeorite impacts and solar charged ions.

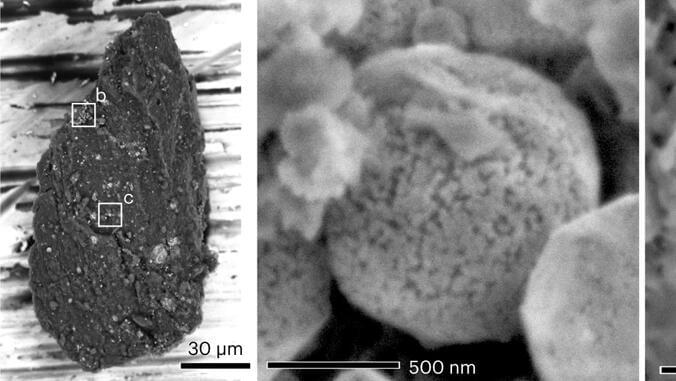

The scientists studied the Ryugu samples to understand the materials reaching Earth’s orbit. They used an electron microscope and found the Ryugu samples’ surface covered with tiny iron and nitrogen minerals. They theorized that micrometeorites carrying ammonia compounds collided with Ryugu. This collision sparked chemical reactions on magnetite, resulting in iron nitride formation.