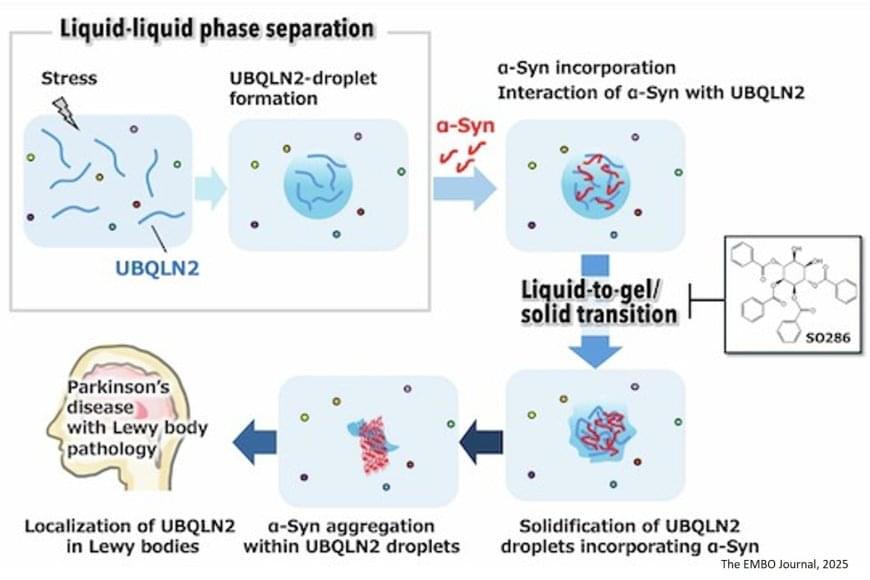

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is an age-related, progressive neurodegenerative disorder. The hallmark of PD pathogenesis is the Lewy bodies (LBs) that accumulate in neurons in the substantia nigra region of the brain, damaging these neurons and leading to the motor symptoms of the disease. α-synuclein (α-syn), a misfolded protein, aggregates and forms fibrils, which leads to the formation of LBs. The exact molecular mechanism behind this aggregation process is yet to be uncovered. With an increasing number of elderly patients suffering from Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative diseases worldwide, it is important to understand the aggregation process, find potential therapeutic targets to mitigate or inhibit the aggregation, and slow down the disease progression.

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), a process where a uniform mixture spontaneously divides into two liquid phases with differing component concentrations, is often considered the reason behind α-syn aggregation. Even though LLPS of α-syn was previously reported, the question remains: are they involved in catalyzing the early stage of aggregation? Ubiquilin-2 (UBQLN2) protein, mainly involved in maintaining protein homeostasis, also undergoes LLPS under certain physiological conditions. Interestingly, it is known to be associated with several neurodegenerative diseases.

Are liquid droplets formed by UBQLN2 catalyzing the α-syn protein aggregation? A team of researchers decided to unravel the involvement of UBQLN2 in α-syn aggregation and fibril formation. “By uncovering the mechanisms that trigger the aggregation process, we hope to find new ways to prevent it and ultimately contribute to the development of disease-modifying treatments,” mentioned the senior author of the study. The study was published in The EMBO Journal.