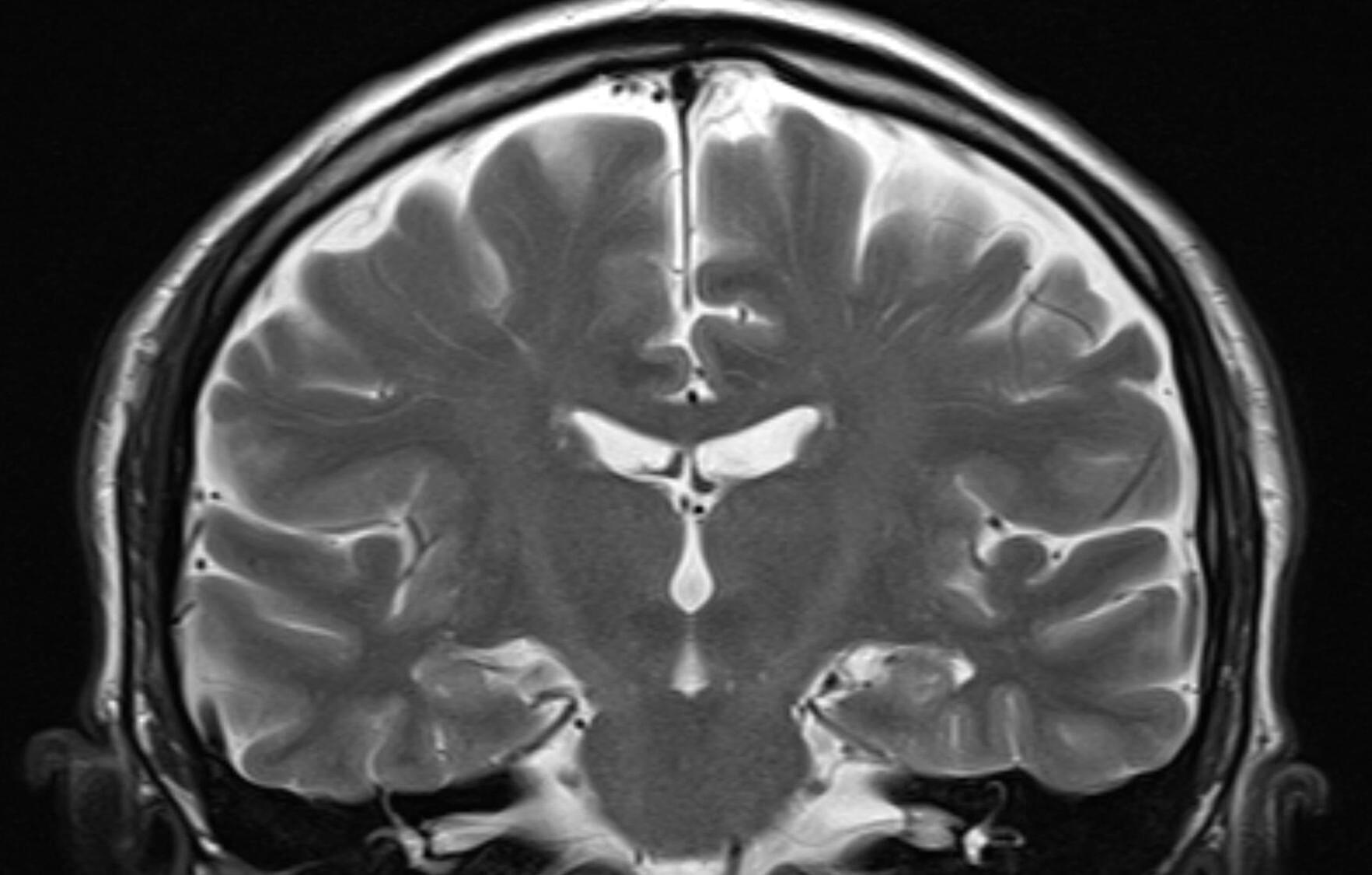

A CDC report has revealed that nine of 68 of children who died of flu this year had brain damage, but it’s unclear whether this influenza-associated encephalopathy is on the rise.

The TOI Tech Desk is a dedicated team of journalists committed to delivering the latest and most relevant news from the world of technology to readers of The Times of India. TOI Tech Desk’s news coverage spans a wide spectrum across gadget launches, gadget reviews, trends, in-depth analysis, exclusive reports and breaking stories that impact technology and the digital universe. Be it how-tos or the latest happenings in AI, cybersecurity, personal gadgets, platforms like WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook and more; TOI Tech Desk brings the news with accuracy and authenticity.

For example: “If you’re worried about immigration, you should be way more concerned about AI” — for the impact on jobs, cultural stability, and social predictability.

Ex-Google Insider and AI Expert TRISTAN HARRIS reveals how ChatGPT, China, and Elon Musk are racing to build uncontrollable AI, and warns it will blackmail humans, hack democracy, and threaten jobs…by 2027.

Tristan Harris is a former Google design ethicist and leading voice from Netflix’s The Social Dilemma. He is also co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, where he advises policymakers, tech leaders, and the public on the risks of AI, algorithmic manipulation, and the global race toward AGI.

Please consider sharing this episode widely. Using this link to share the episode will earn you points for every referral, and you’ll unlock prizes as you earn more points: https://doac-perks.com/

He explains:

Interleukin-17 (IL-17) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that participates in innate and adaptive immune responses and plays an important role in host defense, autoimmune diseases, tissue regeneration, metabolic regulation, and tumor progression. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are crucial for protein function, stability, cellular localization, cellular transduction, and cell death. However, PTMs of IL-17 receptor A (IL-17RA) have not been investigated. Here, we show that human IL-17RA was targeted by F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 11 (FBXW11) for ubiquitination, followed by proteasome-mediated degradation. We used bioinformatics tools and biochemical techniques to determine that FBXW11 ubiquitinated IL-17RA through a lysine 27-linked polyubiquitin chain, targeting IL-17RA for proteasomal degradation.

The synthesis and the characterisation of silicon nanowires (SiNWs) have recently attracted great attention due to their potential applications in electronics and photonics. As yet, there are no practical uses of nanowires, except for research purposes, but certain properties and characteristics of nanowires look very promising for the future.

In the next section, we’ll look at the ways scientists can grow nanowires from the bottom up.

Looking at the Nanoscale.

A nanoscientist’s microscope isn’t the same kind that you’ll find in a high school chemistry lab. When you get down to the atomic scale, you’re dealing with sizes that are actually smaller than the wavelength of visible light. Instead, a nanoscientist could use a scanning tunneling microscope or an atomic force microscope. Scanning tunneling microscopes use a weak electric current to probe the scanned material. Atomic force microscopes scan surfaces with an incredibly fine tip. Both microscopes send data to a computer, which assembles the information and projects it graphically onto a monitor.

Follow Nick on X: https://twitter.com/Telepath_8

Pre-order linkaChart for free: https://linkaChart.ai/?utm_term=ryan2

Generate AI voice audio via ElevenLabs: https://try.elevenlabs.io/xe894d3yv35h.

Neura Pod is a series covering topics related to Neuralink, Inc. Topics such as brain-machine interfaces, brain injuries, and artificial intelligence will be explored. Host Ryan Tanaka synthesizes information, shares the latest updates, and conducts interviews to easily learn about Neuralink and its future.

Sign up for Neuralink’s Patient Registry: https://neuralink.com/trials/

Join the Neuralink team: https://neuralink.com/careers/

I am many.

A dark ambient journey through feeling lost, detached, and emotionally numb.

use this mix for late-night thoughts, study, writing, sleep or to to calm down.

→▫️support me on ko-fi: https://ko-fi.com/blackridge.

→ download on bandcamp: https://blackridgeofficial.bandcamp.com/track/i-dont-recognize-myself-anymore.

→ get the wallpapers: https://ko-fi.com/s/a9d71bee15

#darkambient #backrooms #sad #liminalspace #sleep.

All audio has been modified, mixed, and mastered by blackridge.