Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine have discovered a natural mechanism that clears existing amyloid plaques in the brains of mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and preserves cognitive function. The mechanism involves recruiting brain cells known as astrocytes, star shaped cells in the brain, to remove the toxic amyloid plaques that build up in many Alzheimer’s disease brains. Increasing the production of Sox9, a key protein that regulates astrocyte functions during aging, triggered the astrocytes’ ability to remove amyloid plaques. The study, published in Nature Neuroscience, suggests a potential astrocyte-based therapeutic approach to ameliorate cognitive decline in neurodegenerative disease.

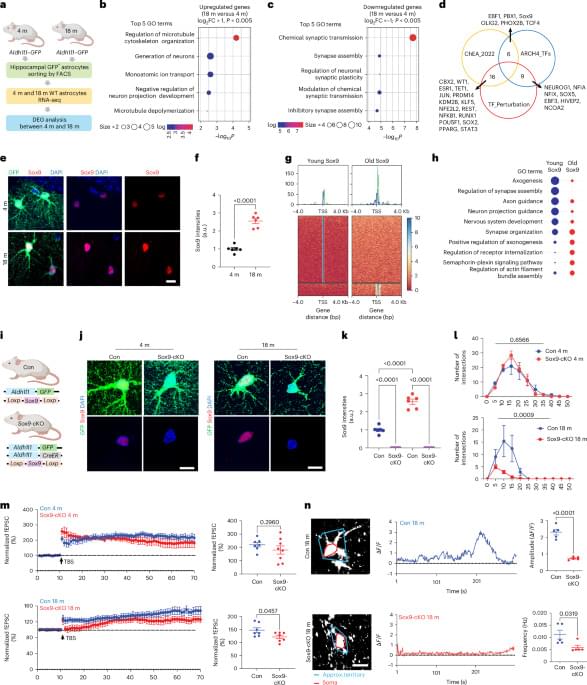

“Astrocytes perform diverse tasks that are essential for normal brain function, including facilitating brain communications and memory storage. As the brain ages, astrocytes show profound functional alterations; however, the role these alterations play in aging and neurodegeneration is not yet understood,” said first author Dr. Dong-Joo Choi, who was at the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy and the Department of Neurosurgery at Baylor while he was working on this project. Choi currently is an assistant professor at the Center for Neuroimmunology and Glial Biology, Institute of Molecular Medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Astrocytes are associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. We found that the transcription factor Sox9 functions to enhance astrocytic phagocytosis of Aβ plaques via MEGF10, and this clearance of plaques is associated with the preservation of cognitive function in mouse models.