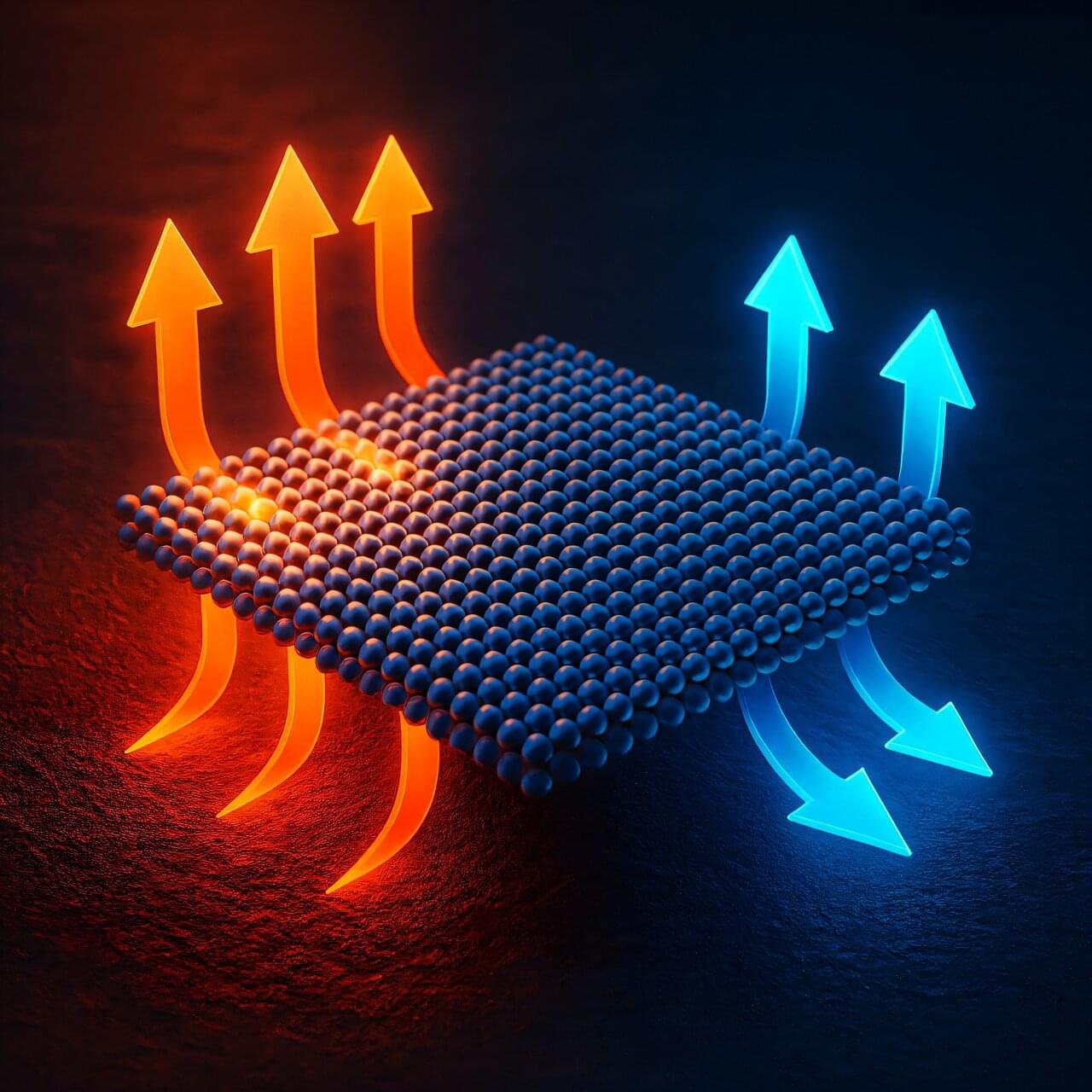

For much of my career, I have been fascinated by the ways in which materials behave when we reduce their dimensions to the nanoscale. Over and over, I’ve learned that when we shrink a material down to just a few nanometers in thickness, the familiar textbook rules of physics begin to bend, stretch, or sometimes break entirely. Heat transport is one of the areas where this becomes especially intriguing, because heat is carried by phonons—quantized vibrations of the atomic lattice—and phonons are exquisitely sensitive to spatial confinement.

A few years ago, something puzzling emerged in the literature. Molecular dynamics simulations showed that ultrathin silicon films exhibit a distinct minimum in their thermal conductivity at around one to two nanometers thickness, which corresponds to just a few atomic layers. Even more surprisingly, the thermal conductivity starts to increase again if the material is made even thinner, approaching extreme confinement and the 2D limit.

This runs counter to what every traditional model would predict. According to classical theories such as the Boltzmann transport equation or the Fuchs–Sondheimer boundary-scattering framework, reducing thickness should monotonically suppress thermal conductivity because there is simply less room for phonons to travel freely and carry heat around. Yet the simulations done by the team of Alan McGaughey at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh insisted otherwise, and no established theory could explain why.