ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is among the most challenging neurological disorders: relentlessly progressive, universally fatal, and without a cure even after more than a century and a half of research. Despite many advances, a key unanswered question remains—why do motor neurons, the cells that control body movement, degenerate while others are spared?

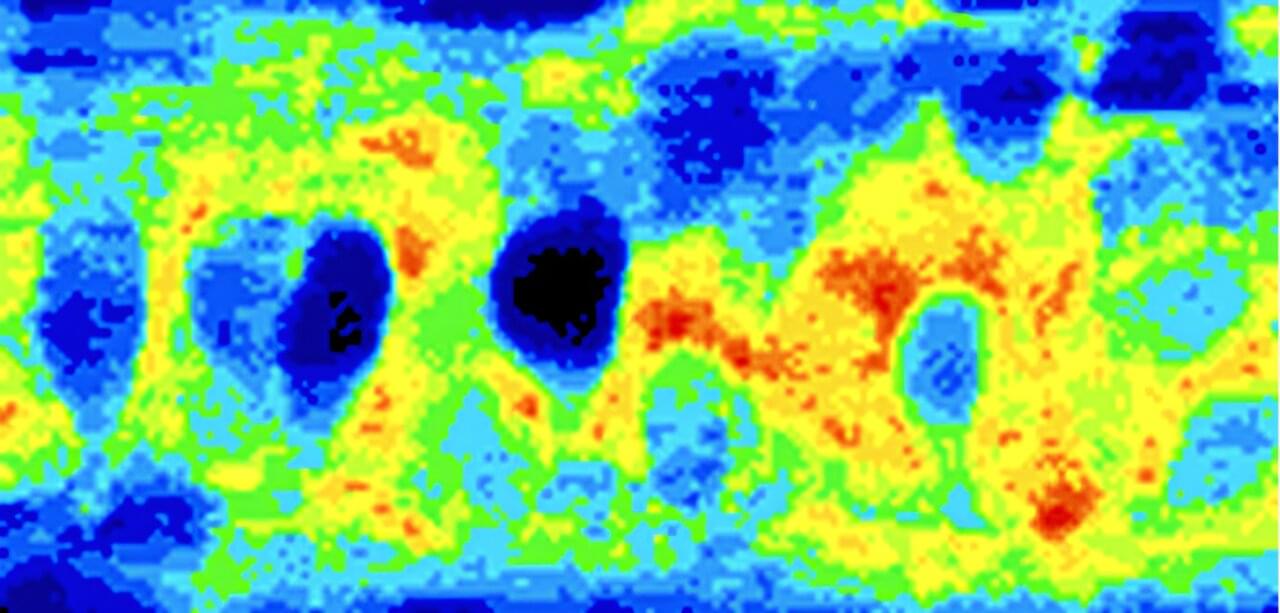

In a study appearing in Nature Communications, Kazuhide Asakawa and colleagues used single-cell–resolution imaging in transparent zebrafish to show that large spinal motor neurons —which generate strong body movements and are most vulnerable in ALS—operate under a constant, intrinsic burden of protein and organelle degradation.

These neurons maintain high baseline levels of autophagy, proteasome activity, and the unfolded protein response, suggesting a continuous struggle to maintain protein quality control.