Solar cells and computer chips need silicon layers that are as perfect as possible. Every imperfection in the crystalline structure increases the risk of reduced efficiency or defective switching processes.

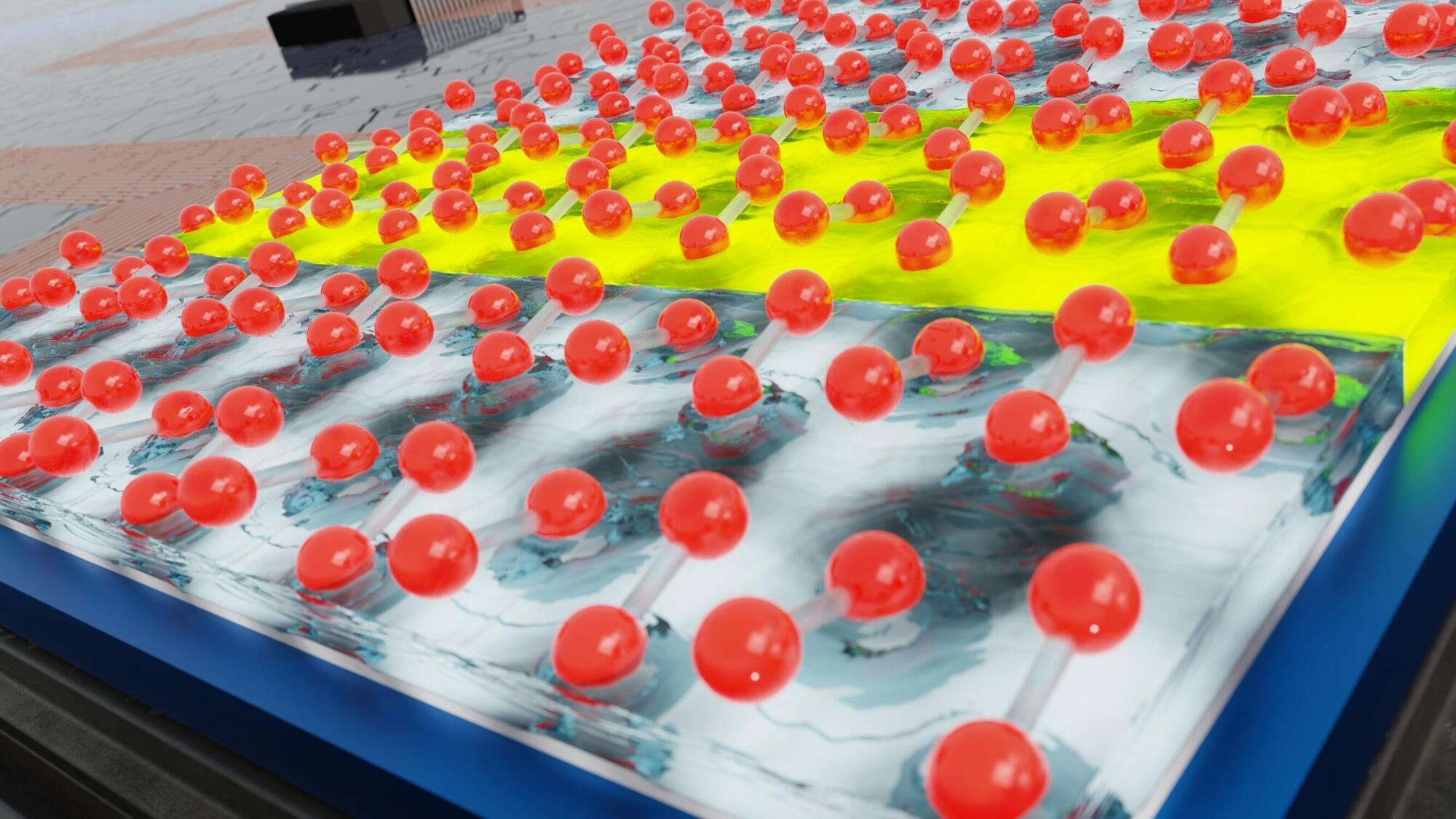

If you know how silicon atoms arrange themselves to form a crystal lattice on a thin surface, you gain fundamental insights into controlling crystal growth. To this end, an international research team analyzed the behavior of silicon that was flash-frozen. The study is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The results show that the speed of cooling has a major impact on the structure of silicon surfaces. The underlying mechanism may also have occurred during phase transitions in the early universe shortly after the Big Bang.