The team took publicly available data from three studies of the Alzheimer’s brain that measured single-cell gene expression in brain cells from deceased donors with or without Alzheimer’s disease. They used this data to produce gene expression signatures for Alzheimer’s disease in neurons and glia.

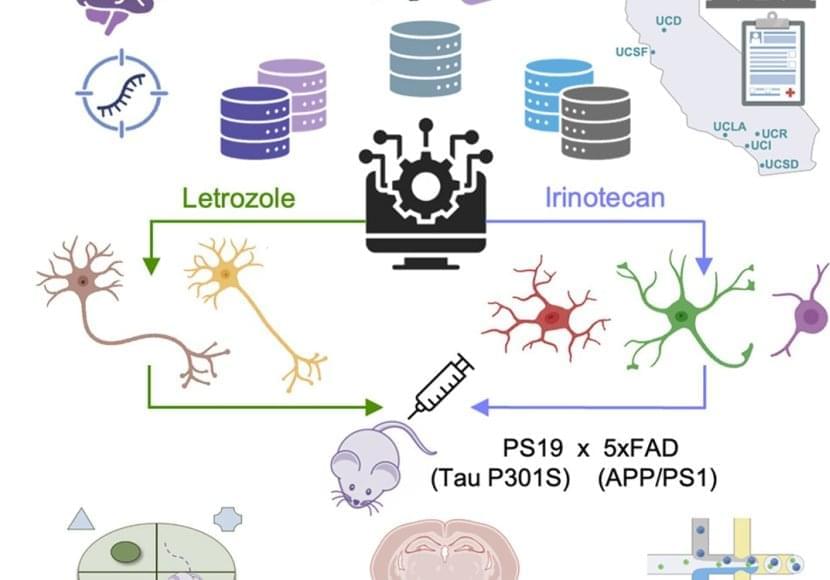

The researchers compared these signatures with those found in the Connectivity Map, a database of results from testing the effects of thousands of drugs on gene expression in human cells.

Out of 1,300 drugs, 86 reversed the Alzheimer’s disease gene expression signature in one cell type, and 25 reversed the signature in several cell types in the brain. But just 10 had already been approved by the FDA for use in humans.

Poring through records housed in the UC Health Data Warehouse, which includes anonymized health information on 1.4 million people over the age of 65, the group found that several of these drugs seemed to have reduced the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease over time.

“Thanks to all these existing data sources, we went from 1,300 drugs, to 86, to 10, to just 5,” said the lead author of the paper.

The authors chose 2 cancer drugs out of the top 5 drug candidates for laboratory testing. They predicted one drug, letrozole, would remedy Alzheimer’s in neurons; and another, irinotecan, would help glia. Letrozole is usually used to treat breast cancer; irinotecan is usually used to treat colon and lung cancer.

The team used a mouse model of aggressive Alzheimer’s disease with multiple disease-related mutations. As the mice aged, symptoms resembling Alzheimer’s emerged, and they were treated with one or both drugs.

The combination of the two cancer drugs reversed multiple aspects of Alzheimer’s in the animal model. It undid the gene expression signatures in neurons and glia that had emerged as the disease progressed. It reduced both the formation of toxic clumps of proteins and brain degeneration. And, importantly, it restored memory.

Scientists have identified cancer drugs that promise to reverse the changes that occur in the brain during Alzheimer’s, potentially slowing or even reversing its symptoms.

The study first analyzed how Alzheimer’s disease altered gene expression in single cells in the human brain. Then, researchers looked for existing drugs that were already approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and cause the opposite changes to gene expression.

They were looking specifically for drugs that would reverse the gene expression changes in neurons and in other types of brain cells called glia, all of which are damaged or altered in Alzheimer’s disease.