AI is a computing tool. It can process and interrogate huge amounts of data, expand human creativity, generate new insights faster and help guide important decisions. It’s trained on human expertise, and in conservation that’s informed by interactions with local communities or governments—people whose needs must be taken into account in the solutions. How do we ensure this happens?

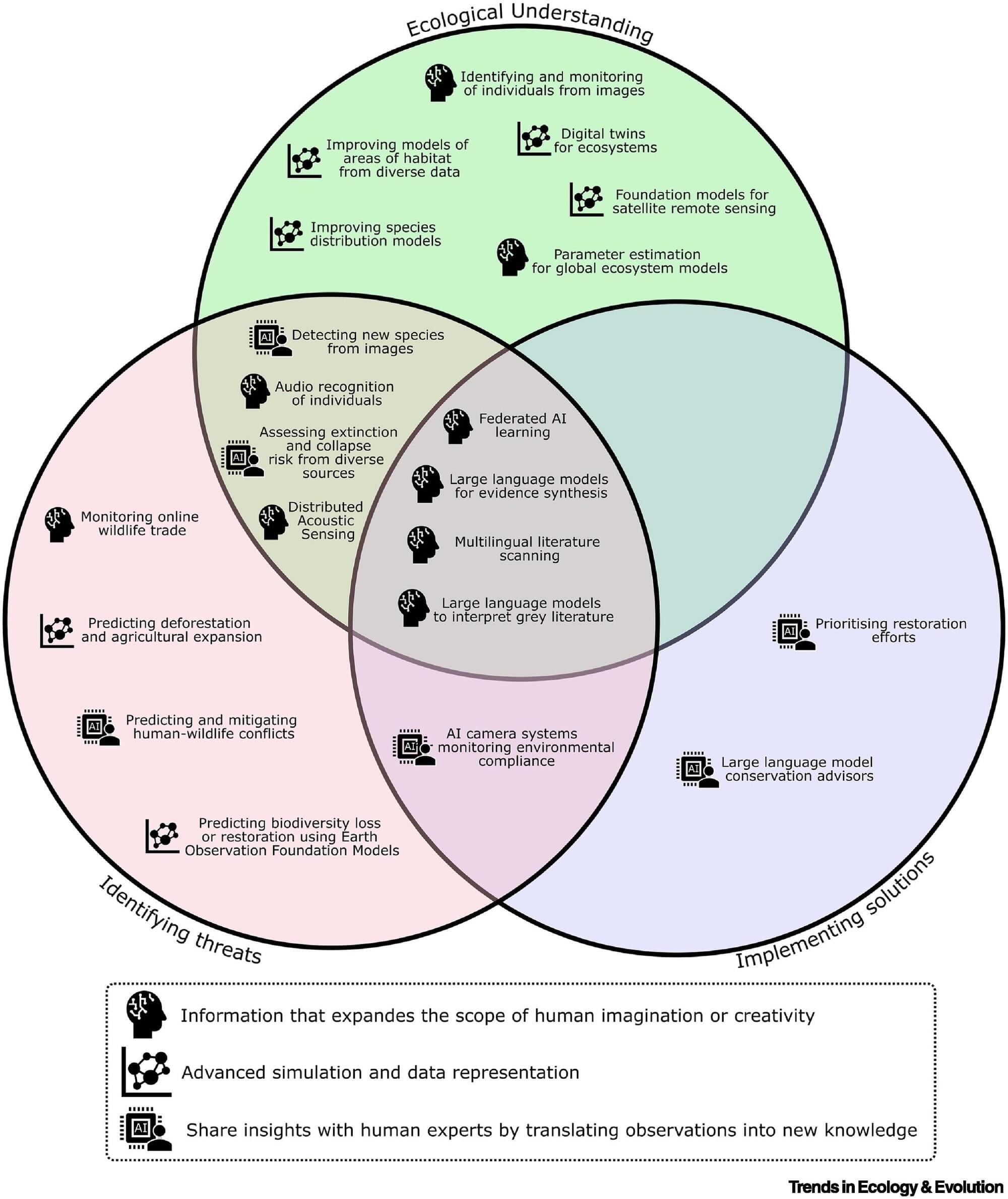

Last year, Reynolds joined 26 other conservation scientists and AI experts in an “Horizon Scan”—an approach pioneered by Professor Bill Sutherland in the Department of Zoology—to think about the ways AI could revolutionize the success of global biodiversity conservation. The international panel agreed on the top 21 ideas, chosen from a longlist of 104, which are published in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

Some of the ideas extrapolate from AI tools many of us are familiar with, like phone apps that identify plants from photos, or birds from sound recordings. Being able to identify all the species in an ecosystem in real time, over long timescales, would enable a huge advance in understanding ecosystems and species distributions.