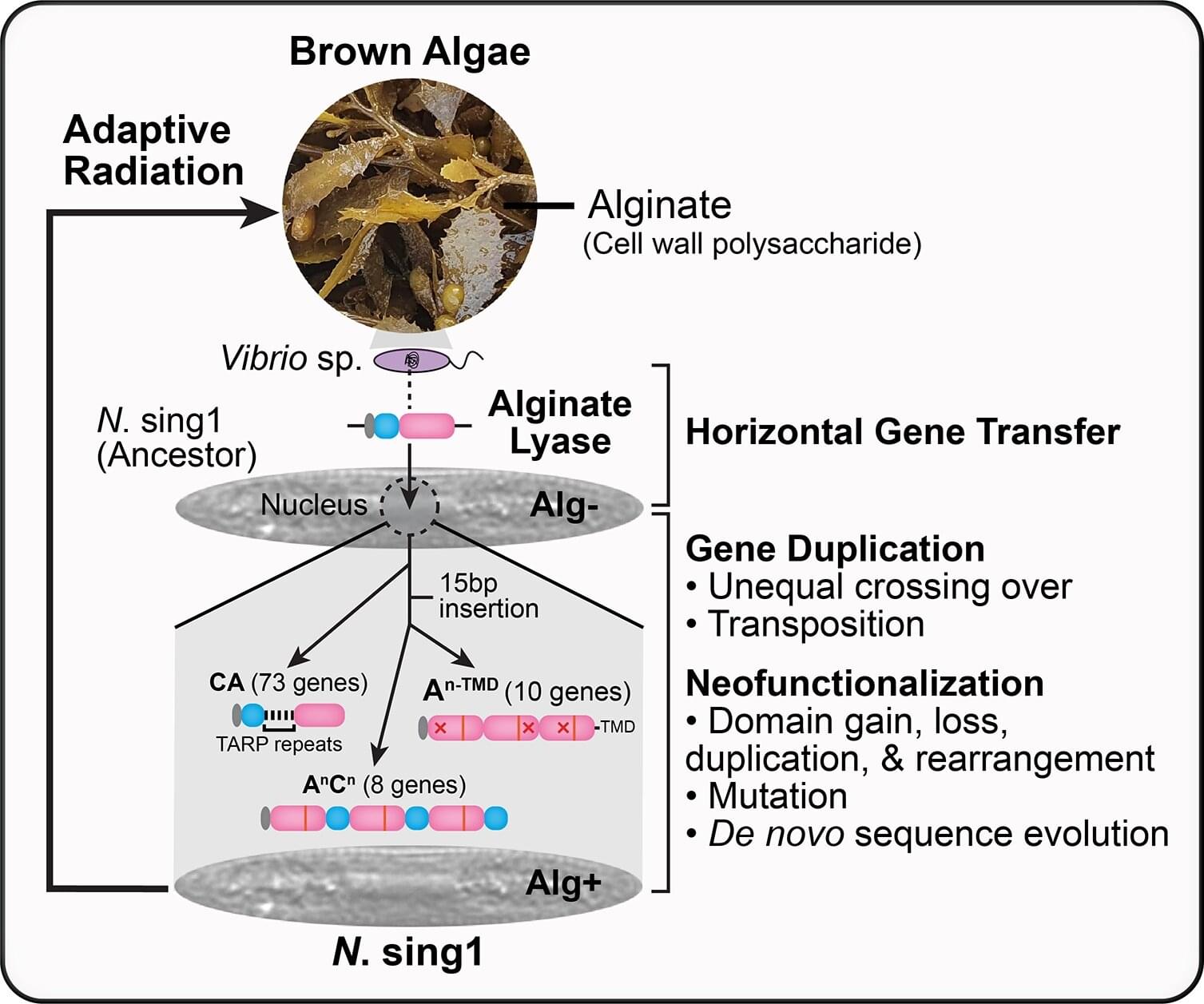

A group of diatom species belonging to the Nitzschia genus gave up on photosynthesis and now get their carbon straight from their environment, thanks to a bacterial gene picked up by an ancestor. Gregory Jedd of Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, Singapore, and colleagues report these findings in a study published in the open-access journal PLOS Biology.

Unlike most diatoms, which perform photosynthesis to generate carbon compounds, some members of the genus Nitzschia have no chlorophyll and instead consume carbohydrates from seaweed and decaying plant matter. Previously, it was unclear how exactly they made this major lifestyle transition, so researchers sequenced the genome of one species, Nitzschia sing1, to look for clues.

N. sing1’s genome sequence showed that the diatom carries a gene for an enzyme that breaks down alginate, a carbon polymer in the cell walls of brown algae—a group that includes kelp and other common seaweeds. The gene originally came from a marine bacterium, and an ancestor of N. sing1 took up the gene and incorporated it into its genome.