Satellite-based optical remote sensing from missions such as ESA’s Sentinel-2 (S2) have emerged as valuable tools for continuously monitoring the Earth’s surface, thus making them particularly useful for quantifying key cropland traits in the context of sustainable agriculture [1]. Upcoming operational imaging spectroscopy satellite missions will have an improved capability to routinely acquire spectral data over vast cultivated regions, thereby providing an entire suite of products for agricultural system management [2]. The Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission for the Environment (CHIME) [3] will complement the multispectral Copernicus S2 mission, thus providing enhanced services for sustainable agriculture [4, 5]. To use satellite spectral data for quantifying vegetation traits, it is crucial to mitigate the absorption and scattering effects caused by molecules and aerosols in the atmosphere from the measured satellite data. This data processing step, known as atmospheric correction, converts top-of-atmosphere (TOA) radiance data into bottom-of-atmosphere (BOA) reflectance, and it is one of the most challenging satellite data processing steps e.g., [6, 7, 8]. Atmospheric correction relies on the inversion of an atmospheric radiative transfer model (RTM) leading to the obtaining of surface reflectance, typically through the interpolation of large precomputed lookup tables (LUTs) [9, 10]. The LUT interpolation errors, the intrinsic uncertainties from the atmospheric RTMs, and the ill posedness of the inversion of atmospheric characteristics generate uncertainties in atmospheric correction [11]. Also, usually topographic, adjacency, and bidirectional surface reflectance corrections are applied sequentially in processing chains, which can potentially accumulate errors in the BOA reflectance data [6]. Thus, despite its importance, the inversion of surface reflectance data unavoidably introduces uncertainties that can affect downstream analyses and impact the accuracy and reliability of subsequent products and algorithms, such as vegetation trait retrieval [12]. To put it another way, owing to the critical role of atmospheric correction in remote sensing, the accuracy of vegetation trait retrievals is prone to uncertainty when atmospheric correction is not properly performed [13].

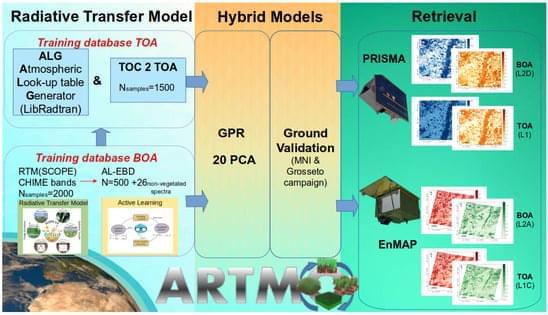

Although advanced atmospheric correction schemes became an integral part of the operational processing of satellite missions e.g., [9,14,15], standardised exhaustive atmospheric correction schemes in drone, airborne, or scientific satellite missions remain less prevalent e.g., [16,17]. The complexity of atmospheric correction further increases when moving from multispectral to hyperspectral data, where rigorous atmospheric correction needs to be applied to hundreds of narrow contiguous spectral bands e.g., [6,8,18]. For this reason, and to bypass these challenges, several studies have instead proposed to infer vegetation traits directly from radiance data at the top of the atmosphere [12,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].