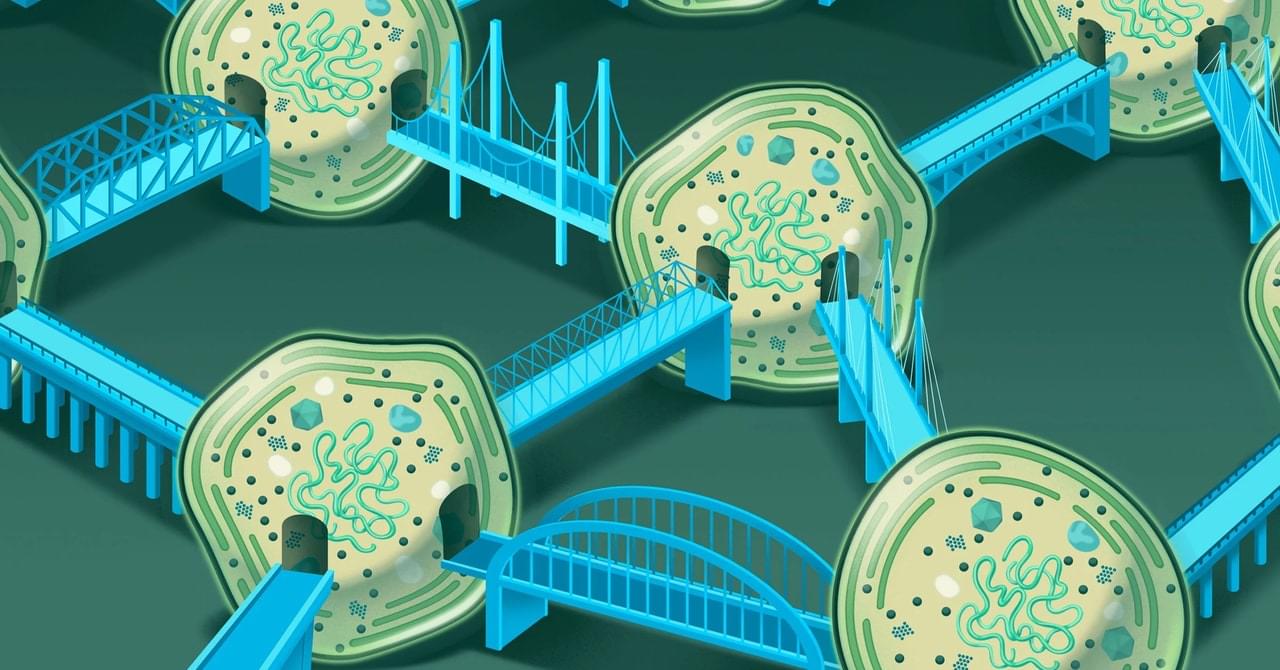

Another question is how bacteria form these tubes, and under what conditions. The tubes are not much longer than an individual cell, and Prochlorococcus, in particular, is thought to spread out in the water column. Muñoz-Marín and her team are curious about the concentrations of bacteria required for a network to form. “How often would it be possible for these independent cells to get close enough to each other in order to develop these nanotubes?” García-Fernandez asked. The current study shows that nanotubes do form among wild-caught cells, but the precise requirements are unclear.

Looking back at what people thought about bacterial communication when he began to study marine cyanobacteria 25 years ago, García-Fernandez is conscious that the field has undergone a sea change. Scientists once thought they saw myriad individuals floating alongside each other in immense space, competing with neighboring species in a race for resources. “The fact that there can be physical communication between different kind of organisms—I think that changes many, many previous ideas on how the cells work in the ocean,” he said. It’s a far more interconnected world than anyone realized.