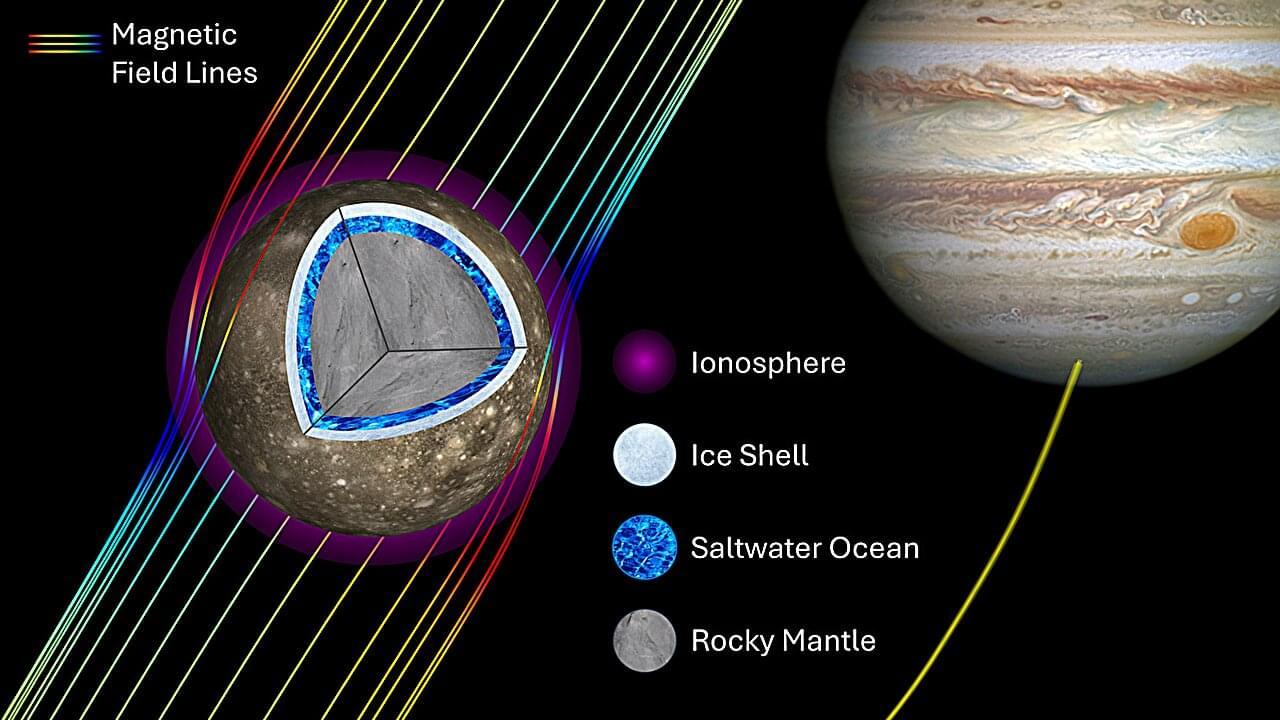

More pocked with craters than any other object in our solar system, Jupiter’s outermost and second-biggest Galilean moon, Callisto, appears geologically unremarkable. In the 1990s, however, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft captured magnetic measurements near Callisto that suggested that its ice shell surface—much like that of Europa, another moon of Jupiter—may encase a salty, liquid water ocean.

But evidence for Callisto’s subsurface ocean has remained inconclusive, as the moon has an intense ionosphere. Scientists thought this electrically conductive upper part of the moon’s atmosphere might imitate the magnetic fingerprint of a salty, conductive ocean.

Now, researchers have revisited the Galileo data in more detail. Unlike in prior studies, this team incorporated all available magnetic measurements from Galileo’s eight close flybys of Callisto. Their expanded analysis much more strongly suggests that Callisto hosts a subsurface ocean.

Almost all ice moons probably have oceans. That seems par for the course with ice moons, even Enceladus, which barely outsizes Great Britain and Ireland, likely has a molten ocean