Ocean currents spin off huge gyres, whose kinetic energy is transferred to ever-smaller turbulent structures until viscosity has erased velocity gradients and water molecules jiggle with thermal randomness. A similar cascade plays out in space when the solar wind slams into the magnetopause, the outer boundary of Earth’s magnetic field. The encounter launches large-scale magnetic, or Alfvén, waves whose energy ends up heating the plasma inside the magnetosphere. Here, however, the plasma is too thin for viscosity to mediate the cascade. Since 1971 researchers have progressively developed their understanding of how Alfvén waves in space plasmas generate heat. These studies later culminated in a specific hypothesis: Alfvén waves accelerate ion beams, which create small-scale acoustic waves, which generate heat. Now Xin An of UCLA and his collaborators have found direct evidence of that proposed mechanism [1]. What’s more, the mechanism is likely at work in the solar wind and other space plasmas.

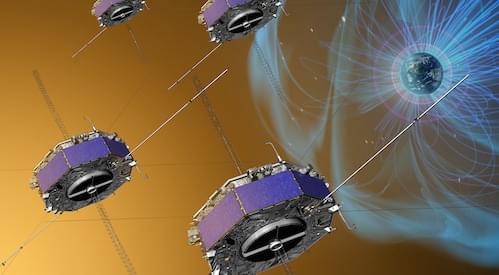

Laboratory-scale experiments struggle to capture the dynamics of rotating plasmas, and real-world observations are even more scarce. The observations that An and his collaborators analyzed were made in 2015 by the four-spacecraft Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission. Launched that year, the MMS was designed to study magnetic reconnection, a process in which the topology of magnetic-field lines is violently transformed. The field rearrangements wrought by reconnection can be large, on the scale of the huge loops that sprout from the Sun’s photosphere. But the events that initiate reconnection take place in a much smaller region where neighboring field lines meet, the X-line. The four spacecraft of MMS can fly in a configuration in which all of them witness the large-scale topological transformation while one of them could happen to fly through the X-line—a place where no spacecraft had deliberately been sent before.

On September 8, 2015, the orbits of the MMS spacecraft took them through the magnetopause on the dusk side of Earth. They were far enough apart that together they could detect the passage of a large-scale Alfvén wave, while each of them could individually detect the motion of ions in the surrounding plasma. An and his collaborators later realized that these observations could be used to test the theory that ion beams and the acoustic waves that they generate mediate the conversion of Alfvén-wave energy to heat.