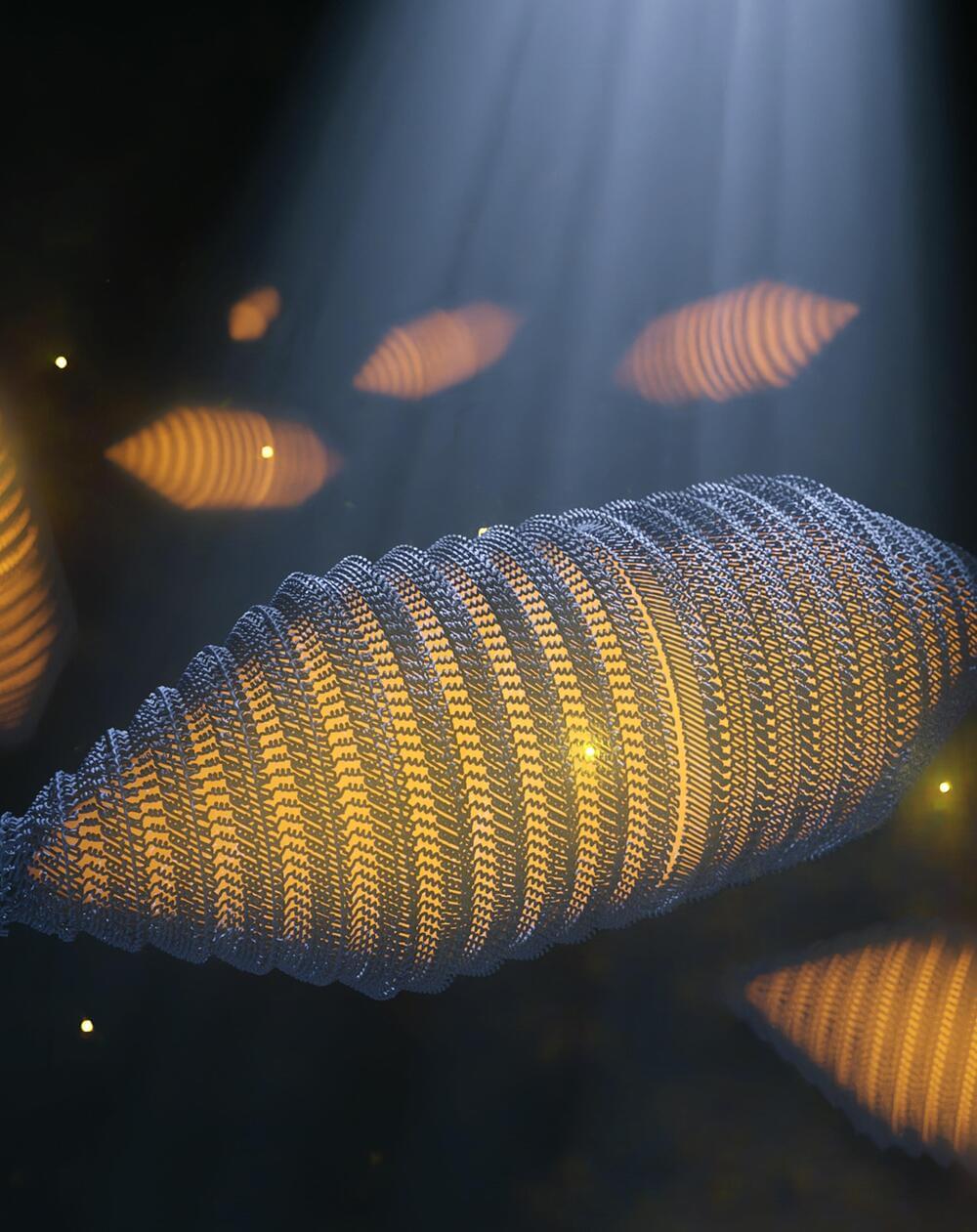

Similar in function to ballast tanks in submarines or fish bladders, many water-based bacteria use gas vesicles to regulate their floatability. In a new publication in Cell, scientists from the Departments of Bionanoscience and Imaging Physics now describe the molecular structure of these vesicles for the first time. These gas vesicles were also recently repurposed as contrast agents for ultrasound imaging.

Gas vesicles (GVs) are hollow, cylindrical nanostructures made of a thin protein-based shell and filled with gas. Similar in function to ballast tanks in submarines or fish bladders, many water-based bacteria use these structures to regulate their floatability. “For example, certain cyanobacteria use gas vesicles to float to the surface in order to harvest light for photosynthesis, a phenomenon sometimes seen at enormous scale in toxic algal blooms,” says Arjen Jakobi, Assistant Professor at the Department of Bionanoscience.

There are very specific requirements for such structures: for bacteria to stay afloat, GVs must occupy a substantial proportion of the cell, which involves forming compartments that extend over hundreds of nanometers in size. To maximize floatability, the shell must be constructed from minimal material. At the same time, the shell needs to provide resistance to the pressure from the surrounding water to maintain the ability to float with changes in water depth. GVs have therefore evolved as rigid, thin-walled structures composed of a single protein that repeats many thousands of times to form the GV shell.